Jay Trimble on user-centered design, Agile, and design thinking at NASA

The O’Reilly Design Podcast: Solving problems, user-centered design, and culture at NASA.

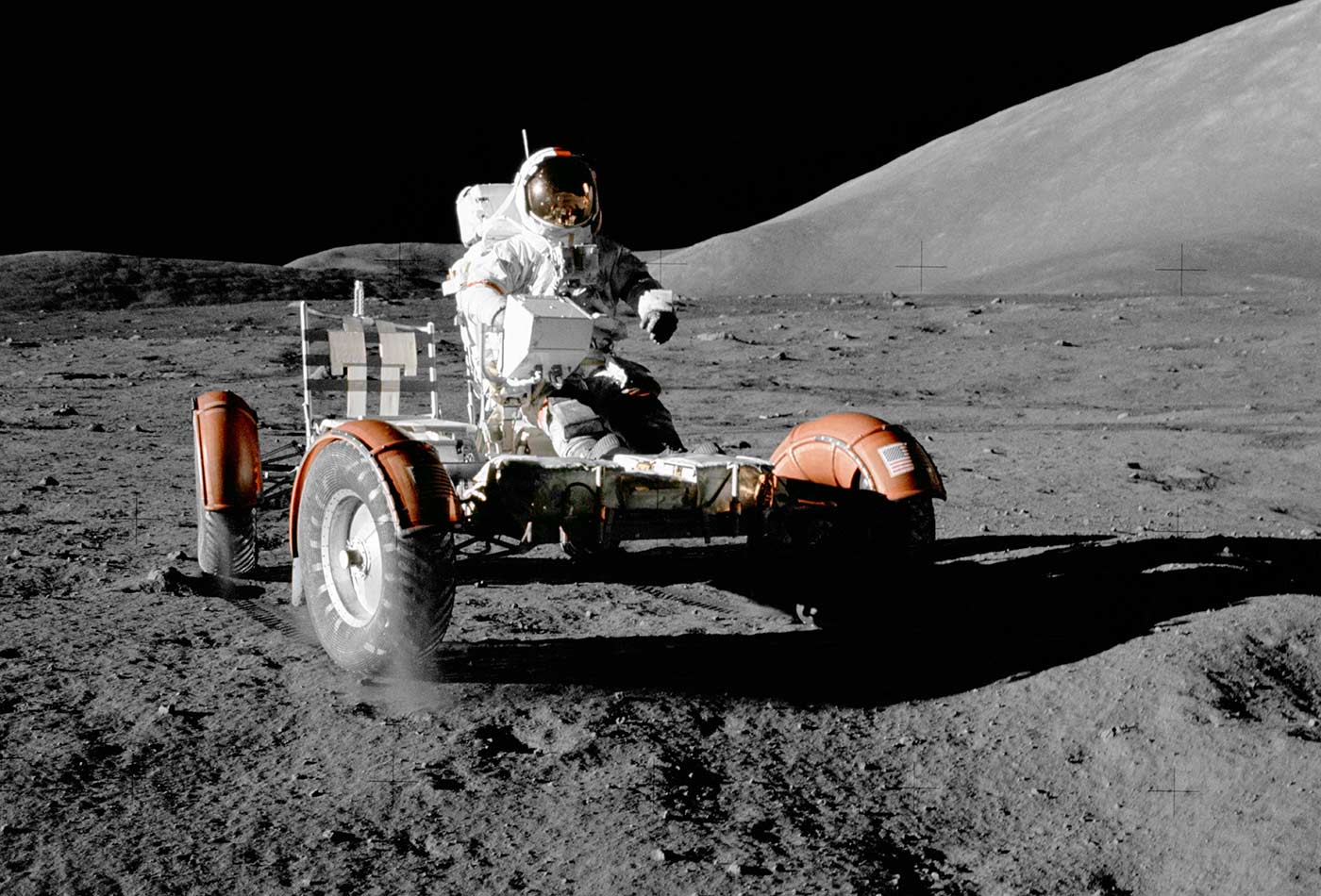

Apollo 17 mission, 11 December 1972. (source: NASA on Wikimedia Commons)

Apollo 17 mission, 11 December 1972. (source: NASA on Wikimedia Commons)

In this week’s Design Podcast, I sit down with Jay Trimble, mission operations and ground data system manager, for the Resource Prospector Lunar Rover Mission at NASA. We talk about applying Agile, adopting design thinking and user-centered design, and what he and his team rely on to design and build software for mission control.

Here are some highlights from our conversation:

Agile at NASA

As far as Agile goes in my group, it was probably around 10 years ago when we started to become Agile; we didn’t really set out with a stated goal of being Agile, at least not in the beginning. We were having issues with our software development and we were trying to make it better, and by iteratively solving problems, we found we were starting to match—what was then certainly much less mainstream than it is now—the Agile method. We had a six-month delivery cycle. We would take a set of requirements, and then we’d deliver six months later; we were out of sync with our customer because of that.

One of the first things we did is shorten our delivery cycle. Now, we’re at a three-week cycle and nightly builds. These are fairly mainstream things now, but they were more new then, and we went from getting feedback every six months from our customer—I mean feedback on software, not feedback on designs—to getting feedback daily. We would put out a nightly build, and every time we had a new feature, we’d get direct feedback from a customer the same day. That’s just one of many examples of how we were trying to solve the problems that we had, and we also had a nice kick-start along the way from IBM. I talked to some colleagues at IBM, and they had been through some of this process of going Agile; because they were a large organization, it seemed very relevant, and we had some good technical interchanges with them to help us kick-start that.

Management was very supportive, but once again, we didn’t plant a flag in the ground and make a proclamation, ‘We’re going Agile’; we just solved problems.

Design thinking at NASA

I think of NASA, really, as a hardware-focused system engineering organization. I don’t mean to say that we don’t use software and that we don’t emphasize software, that it’s not critically important—because it is all of those things—but really, when people think of NASA, they think of rockets rising up on launchpads or rovers landing on Mars or a spacecraft flying by Pluto.

We couldn’t do those things without software, so in terms of design thinking, and this is also true for our Agile development methods, we really started with software where we felt we had more familiarity with how to apply it. System engineering thinking would be, “What are my requirements? How do I validate those requirements? How do I reduce my risk?” Design thinking—in that environment, at least in the way we have approached it—is providing a pathway to not getting overly focused on your first idea. We know this is an issue, right? It’s an issue that design thinking addresses. I have my first idea, I take it and become very invested in it, and I run with it. When you’re saying, ‘What is my requirement,’ it’s very easy to go down that path. We try to provide an environment that is open to ideation, that is open to evaluating ideas early, where we prototype ideas, where we iteratively move things forward.

We have also done user engagements through ethnography—in some cases, interviewing users, doing things you don’t typically do in a system engineering process. Now, there are other groups here who apply human computer interaction and other things. My group is focused on just one set of design methods. We started, as I said, with software and we became Agile, then we integrated the user-centered design techniques we were using at the time into those Agile workflows, which goes back to something I was talking about earlier where we’re using the nightly build, the software build, and having our designers involved, getting daily feedback from our users.

Now that we built some confidence in doing this with software, we’re starting to move it to other areas, which is also very exciting. I mentioned the Resource Prospector mission to the moon, looking for water at the poles. There, we’re taking some of the mission processes of, how do you drive a rover doing near real-time command and control? By that, I mean it’s only a matter of seconds until we get the telemetry back, so we know what happened versus if you’re controlling a rover on Mars, it could be up to 40 minutes before you know what happened.

It’s a very different way of interacting with a vehicle off-world. We are doing early prototyping, early simulations, where we put the team together and we’ll try something, then iterate on those ideas, refining them and building on them. In system engineering, some of this prototyping would be called a ‘risk reduction prototype,’ so it fits the mindset. Some of this is a matter of mapping mental models, where you are bridging these different ways we think so that people can understand. If I say ‘a risk reduction prototype,’ that’s a great fit in system engineering, and of course, prototyping is integral to design.

The tools of NASA

I mentioned ethnography; we do user interviews, we do user observations in context, we do a lot of wire framing, we do a lot of prototyping, and we do journey maps. We just did our first design sprint, which was a Google Venture-style design sprint; for that, we brought in an outside facilitator to help us out, but I will also say that we had spent years working on and applying participatory design techniques. The design sprint actually has a lot of similar methodologies to what we were doing in participatory design, but it certainly takes it much further and puts it together into this amazing way of validating a concept in a very brief period of time.

I thought participatory design was a great way to bring in stakeholders and address some of the issues we were talking about earlier. We would sit around a circular table, and we had a facilitator who was an expert in these techniques; we would bring in all of the stakeholders, and through these participatory design methods, we would create a shared understanding, a common language, and we would get the user directly involved and invested in the design work we were doing. I thought it was great stuff. In order to do that, you have to have a tremendous amount of access to your users; we don’t always have that, but when we do, participatory design can be a great technique.