Enterprise IoT: IoT strategy execution

A dedicated methodology for businesses preparing to transition toward IoT-based business models.

Photo of a Railway Post Office at work on the Chicago and North Western, 1965. (source: Association of American Railroads on Wikimedia Commons)

Photo of a Railway Post Office at work on the Chicago and North Western, 1965. (source: Association of American Railroads on Wikimedia Commons)

Many large companies find it extremely difficult to deal with disruptive paradigm shifts. This is not a new observation. In 1942, Joseph Schumpeter coined the seemingly paradoxical term “creative destruction” as a way to describe “the free market’s messy way of delivering progress” [EC1] (actually, it can be traced back to the works of Karl Marx, but let’s not go there…). Probably the most cited example of a company that was unable to deal with disruptive technologies is Kodak. Although Kodak was one of the inventors of digital photography, the company failed to transform itself from a leader in film-based photography to the new, digital business models. Schumpeter’s gale seems like a perfect summary of the dilemma many large companies face—the inability to reinvent themselves from the inside, and the extremely fast pace at which startup companies are creating new digital businesses on the green field.

In our view, there was never a distinct, defining moment in the history of Kodak that initiated its decline—the company’s decline took more than a decade and had multiple different causes. In the context of the IoT, every company has to ask itself how much of a potentially disruptive paradigm shift the IoT represents, and how long this shift will take in its respective vertical markets. These are exactly the issues that the Ignite | IoT Strategy Execution methodology aims to address: create a better understanding of what the transformative IoT roadmap should look like for an individual company, learn how a portfolio of IoT opportunities should be managed, and establish how individual IoT initiatives can be identified, approved, and executed.

Now, we don’t expect many CEOs to read this book and then directly apply the Ignite methodology to their IoT strategy. However, many managers will get ideas from this chapter that they should be able to apply to their own situation and maybe use them to influence top management. And possibly even more importantly, we have been asked by many people working at the project level how they can better sell their ideas, get resource commitments, or generally ensure management buy-in for their IoT projects. In this kind of situation, it is not only important to understand how you can structure your own IoT business case; you will also need to look at how this business case is seen by management in the context of other business opportunities—and how you should develop your own business case in order to sell it successfully.

Most of what we discuss in this chapter will be more interesting for those in the “machine camp” who work for large industrial companies with complex product portfolios. However, people in the “Internet camp” working for the large incumbents in this space may also be very interested.

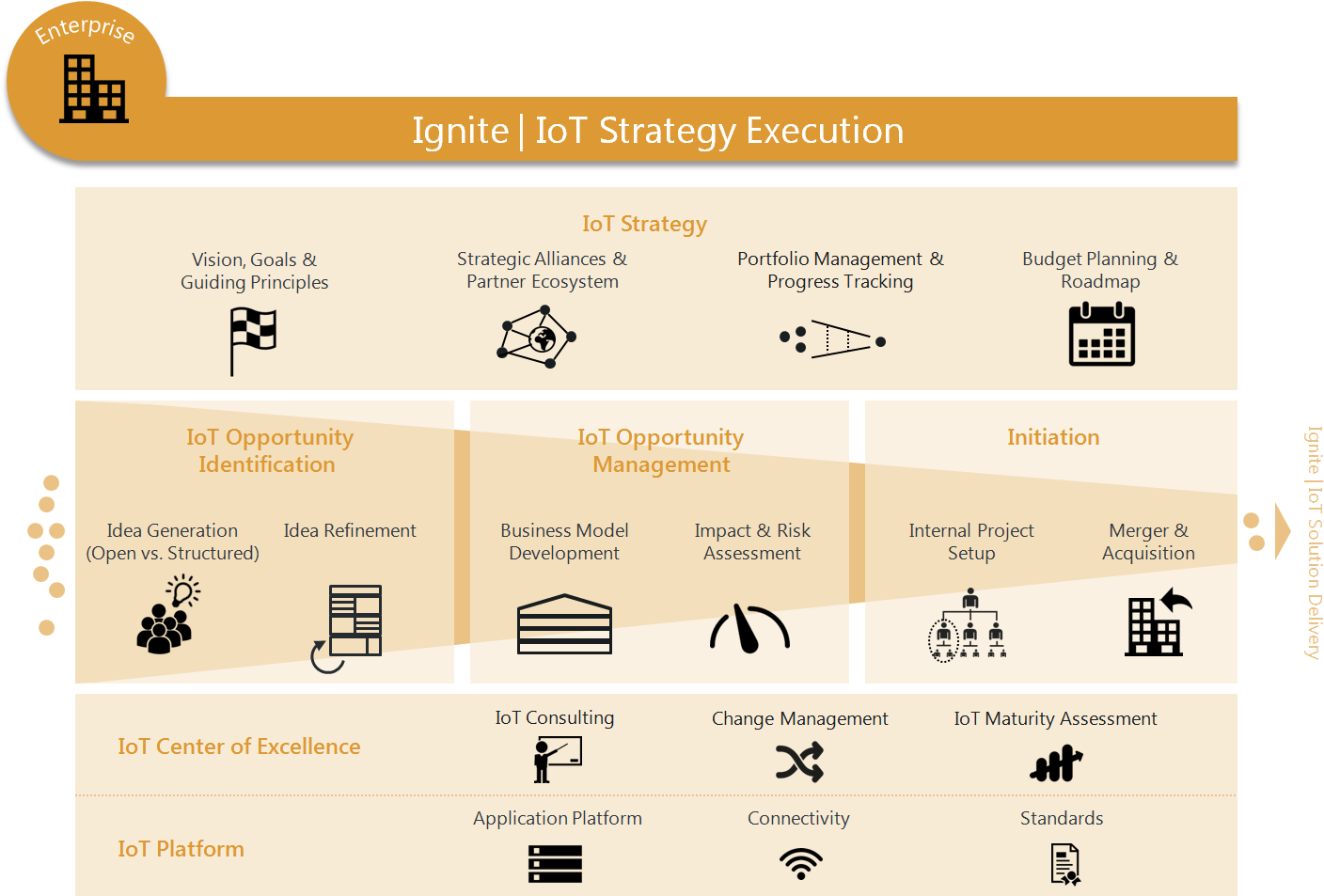

Figure 1-1 summarizes the key elements of the Ignite | IoT Strategy Execution framework, which is divided into six areas: IoT Strategy, IoT Opportunity Identification, IoT Opportunity Management, Initiation, IoT Center of Excellence, and IoT Platform.

A company’s IoT Strategy needs to reflect the extent and speed at which it should shift toward the IoT: Should the company become a pioneer and attempt to gain rapid market share but at the risk of failure? Or should it become a follower that will only implement a new IoT solution if there is certainty that the customer will accept it and buy? Some companies consider the IoT as just one of many important paradigm shifts happening at the moment, and invest only limited resources into IoT adoption. Other companies see the IoT as the fundamental paradigm shift of the next decade, and have made large investments in IoT programs alongside the establishment of far-reaching internal change management programs. The IoT strategy needs to provide vision, goals, and guiding principles. It should also provide a high-level description of how strategic alliances and partner ecosystems in IoT-related business areas should be developed. Finally, it needs to manage the portfolio of IoT opportunities and projects, as well as budget planning and management of the IoT roadmap.

IoT Opportunity Identification, the generation of innovation ideas for IoT solutions, can either happen as an open process, which draws on the innovation potential of employees, customers, and developers, or as part of a more structured approach, where ideas are derived from a given context, such as the company’s value chain, for example. Ideas that show the most promise need to be elaborated in more detail, using templates for idea refinement, for example.

Having made it through the first quality gate, the most promising ideas are then refined as part of the IoT Opportunity Management phase. A more detailed business model has to be prepared in order to assess feasibility and the business case. The following Impact & Risk Assessment phase ensures that all possible outcomes of the business model are given sufficient consideration.

Once an IoT opportunity has been approved, it can be moved into the Initiation stage. In this stage, management has to decide on the best way to set up the initiative: as a dedicated internal project, as a spin-off, or even as an M&A project, for example. For internal projects, these activities interface with the Ignite | IoT Solution Delivery methodology.

An IoT Center of Excellence (CoE) can help new projects gain momentum faster, by providing IoT consulting and change management support, for example. IoT maturity assessments can help an organization to better understand where it currently stands with respect to IoT adoption.

Finally, it can make sense for large organizations to provide a shared IoT Platform that can be used by multiple projects to develop their solutions. This would usually include an IoT application platform, connectivity solutions, and technical and functional standards.

Again, we are not saying that every large organization that is serious about IoT has to develop these elements to the full extent. In fact, some of reactions we got from people in the startup world were along the lines of “Wow, you machine guys really feel better if you can look at structured flowcharts with boxes and arrows between them, right?” This might be a fair assessment from a startup’s point of view. However, the importance of getting people in a large, multistakeholder organization to agree on a joint strategy cannot be underestimated. And being able to efficiently communicate this strategy is an important first step toward this goal.

Another caveat relates to the generic nature of the “IoT Strategy.” Large companies usually already have established corporate strategy management and portfolio management processes, different types of CoEs, shared IT platforms, and so on. So in most cases it will be necessary to look at these established structures and see how they will need to be adapted to reflect the different elements described in the Ignite | IoT Strategy Execution methodology. However, we believe there is value in describing them here from a generic, IoT-centric perspective, so that individual organizations can adapt them easily based on their own needs.

IoT Strategy

On a management level, the first question to be answered is “How seriously do we actually have to take this IoT hype?” Is this really the single most important disruptive force that will change our business in the coming years, is it one of many, or does it not matter at all? In a large, highly diversified company, the answer to this question may differ from business segment to business segment. Furthermore, the question may not come in the form of a question about IoT. It may come as a question like “How important will the connected vehicle be to me as an OEM, and when will it impact my business?” Or an industrial equipment company might ask “What is the strategic importance of connected services in the context of our overall servitization strategy?” Some CEOs might actually hire a management consultancy firm to answer these questions, while others will decide this with their inner management circle based on experience and gut feeling.

What seems important is that the questions, and the answers to these questions, are explicitly articulated, and form a solid basis from which the management team can derive a vision, goals, and guiding principles.

This vision could include things like:

-

ACME Industries will transform itself from a pure product business into a market-leading provider of connected industrial services.

-

ACME Automotive will establish itself as the leading provider of an open, connected vehicle application platform.

This should be accompanied by a set of more concrete goals and business objectives, for example:

-

In the product areas of X, Y, and Z, we will generate X% of annual revenue from connected services.

-

In the product areas P, Q, and R, we will reduce maintenance costs by X% based on connected services.

A set of key strategies and guidelines should support the following:

-

ACME Corp will establish an internal, IoT-focused, open innovation program in combination with a strategic value chain analysis to identify key opportunities.

-

ACME Corp will earmark $X million in funding for the top 10 IoT opportunities.

-

The split between internal and external projects and M&A focused activities should be roughly X% to Y%, subject to analysis of individual cases.

-

In the area of XYZ, we should build an open partner ecosystem, while in the area of PQR, we should aim to control the platform and only allow for selected partners, such as A, B, and C, for example.

Senior management should also take on personal responsibility for a list of strategic tasks, for example:

-

The CEO will change the annual budget process to reflect IoT priorities.

-

The CEO will contact partners A, B, and C to initiate partnership discussions.

-

The CFO will work with the M&A team to allocate X% of the M&A budget to the new IoT strategy.

IoT Opportunity Identification

Once the overall strategic framework has been defined, the next question to be asked is: How can we break this all down into concrete opportunities? Say an OEM has agreed that they want to pursue the connected vehicle as a key strategy, and have allocated a set amount of resources to the strategy in general. As we saw in not available, the connected vehicle is a very broad concept, with many different related opportunities, from connected horizon initiatives to community-based parking. And most likely, there are further promising opportunities in this area that have not even been identified yet. So how can an OEM that has identified the connected vehicle as a strategic area ensure that the best opportunities are identified and eventually funded?

IoT Opportunity Categories

The first thing that is helpful is to come to an agreement within the organization on what types of opportunities are to be looked for in the context of IoT. Questions like “Let’s see what kind of things we can connect up and maybe add some services to” are not going to be a helpful approach. Instead, it can be helpful to provide an overview of the most likely categories or opportunities that should be identified.

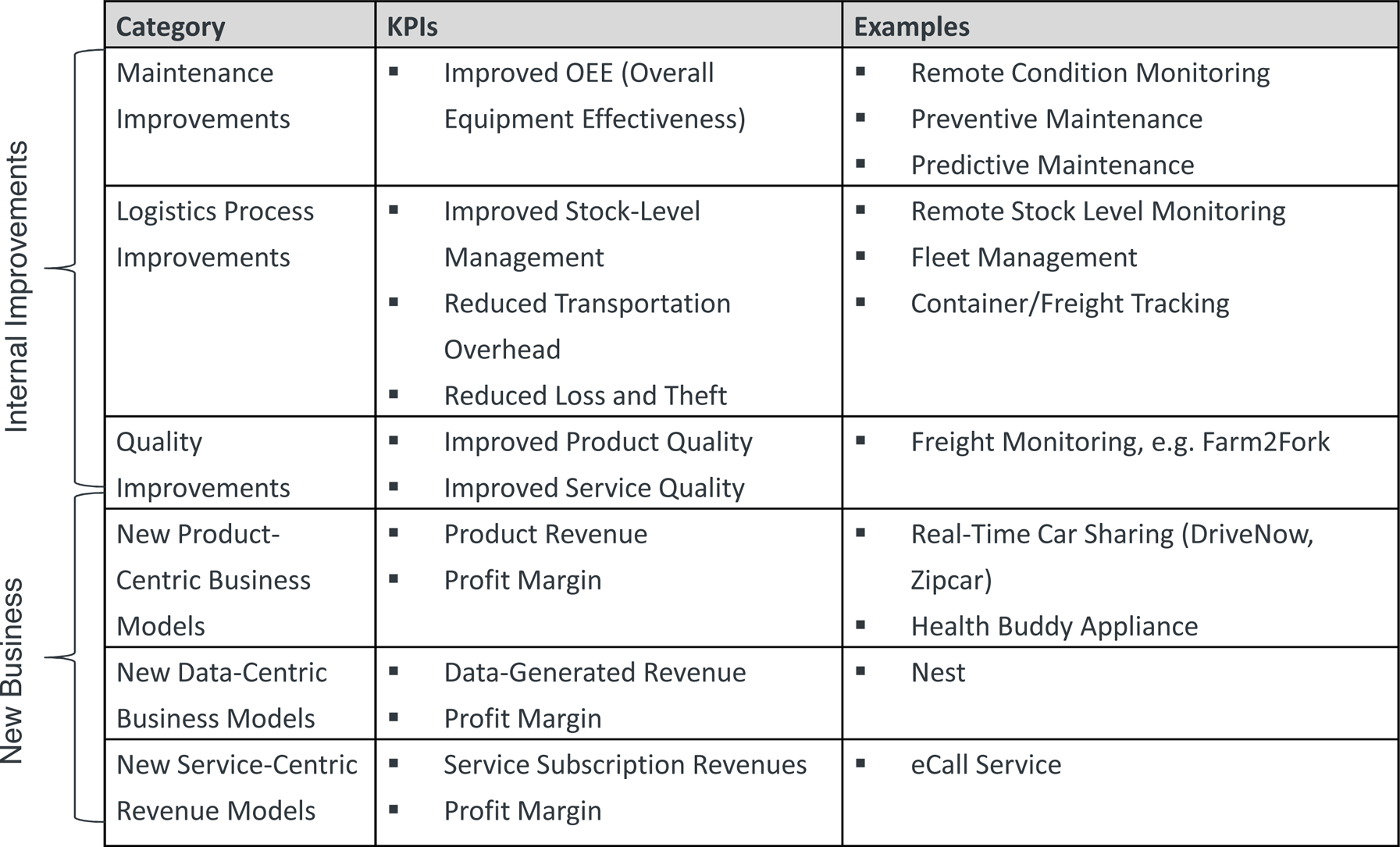

For example, Figure 1-2 differentiates between new business and internal improvements on the top level. For each of these two areas, a number of general categories like maintenance improvements or data-centric business models are defined, together with some typical KPIs and examples.

Applying this example to your own business domain can be helpful in structuring the search for the best IoT opportunities.

IoT Idea Generation Process

The next step is to understand the different options that are available for managing the idea generation process in a large company, and how to best apply these options to the generation of IoT business opportunities. There are usually two main ways to generate ideas in a large company: either open idea generation (green field approach), or a more structured idea generation approach, where ideas evolve in a given context, such as how they relate to the company’s current value proposition, for example. The latter approach is usually organized as a top-down process. It typically involves an internal strategy team or external consulting firm that performs a thorough analysis of the market, including the partner ecosystem, and the potential impact of the IoT on the company’s and even the industry’s value chain.

Open idea generation typically produces more disruptive ideas. Companies should therefore have multiple channels in place to gather these ideas—channels such as employees, customers, and even developers.

Example: Bosch Web 3.0 Platform

Bosch has implemented a web-based ideation platform called “Web 3.0 Platform,” that allows Bosch employees (or distinct communities) to input and vote for ideas. Quick Scan is an input and filter method (evaluating market, revenue, and feasibility) that provides an initial rating of the idea when it is first input. The core team (employees of Bosch Corporate and business units) conducts dedicated workshops with subject matter experts to assess the ideas in more detail. Usually, the Osterwalder canvas is used to draft the business model for the selected ideas. Having passed another quality gate, projects are set up. For more details on this process, see Business Model Development.

So far, there are more than 600 ideas related to connected vehicles in the database (collected within a timeframe of 18 months), and the first concrete project launches, such as “360 degree parking,” for example. We asked Bosch representatives responsible for the Web 3.0 Platform about their experiences with the platform. Peter Busch, Senior Expert at Bosch Corporate Research, spoke about the challenges facing project teams when the company’s business plan has already become obsolete by the time an idea has reached a certain quality gate. The “window of opportunity” for IoT ideas cannot be aligned with company business plans defined in earlier years. Because Internet-based product lifecycles (including development phase) are much shorter than those applicable for traditional products in the mobility area, this alignment issue becomes even more challenging. On the one hand, there is huge pressure to produce IoT ideas quickly, while on the other hand, large companies especially have a very lengthy planning and development phase. He added that there are further IoT-specific aspects causing issues: the IoT opens up a transversal context, touching on several domains; something that contradicts the vertical focus of Bosch business units. “Since IoT ideas are often relating to multiple business units, it is difficult to get all right people on board,” explains Sven Kappel, Senior Expert for Embedded Software & Connected Services at Bosch. A key factor in the success of the project is to identify the business units’ common interests in order to align their involvement, in spite of their differing strategies.

Another issue identified by Sven relates to the fact that the organization does not always have the capacity to identify ideas and develop them in a timely manner. It therefore requires new ways of finding resources, such as open source communities, or the Bosch Startup Platform (BOSP), the company’s own business incubator established in 2014.

Employee Incentives

Another important point to consider is the question of how you want to encourage continuous innovation among your employees, with the aim of improving the company’s processes and coming up with new solutions.

There are good reasons to involve employees in the innovation process: They might be closer to end users and the customers they serve, accumulating more knowledge of their needs. Furthermore, they usually represent multiple functions, ranks, and locations, reducing the risk of “silo mentality.”

There are established programs offering incentives to employees at large organizations. The Siemens 3i Program (the 3 i’s stand for “Ideas, Impulses, and Initiatives,” the name given to a system for submitting suggestions established in 1997) is such an example: employees can submit their ideas for new services or process improvements and receive monetary reward in case of success, such as, for example, a reward of 10% of the annual cost savings. In Germany, more than 100,000 ideas are brought to life per year within the 3i Program [SI1].

According to Peter Fürst, Managing Partner at five i’s innovation consulting GmbH, money is definitely not the only incentive and should be handled with care. Especially for new product and new business ideas, appreciation and visibility of ideas and accomplishments support motivation.

Peter Fürst believes that it is not only the submitter of an idea who should benefit from an incentive- or appreciation-based system: many ideas grow from the impetus of more than one person, so the achievements of all these creators of an idea should be honored. Otherwise people will cease discussing their ideas, fearing the other person might steal the idea and submit it first. Within such a climate, creativity is deadened rather than supported.

One possible way of addressing this could be to establish an “innovators club” that offers its members attractive benefits in terms of continuing education and social networking, such as giving them the opportunity to visit interesting trade fairs and conferences, for example.

Idea Refinement

Many good ideas do not look too pretty when first conceived. They need care to grow and mature before they can really convince possible stakeholders. Fortunately, there is no shortage of ideation methodologies that offer support for idea refinement. At this point, we would like to highlight two approaches that we found helpful.

The first approach is the St. Gallen Business Model Navigator™ [BM1]. The University of St. Gallen (USG) has done extensive research into different types of business models and the reasons why they are successful. Based on an analysis of more than 250 business models, USG has identified a set of repetitive business model patterns that can be applied to construct new business models. The USG now offers a set of cards detailing the different business model patterns that can be used to refine new business ideas, offered during regular workshops held by the university. This, in combination with the research USG has done on IoT-specific business models, is now a powerful tool for creating and refining IoT business models.

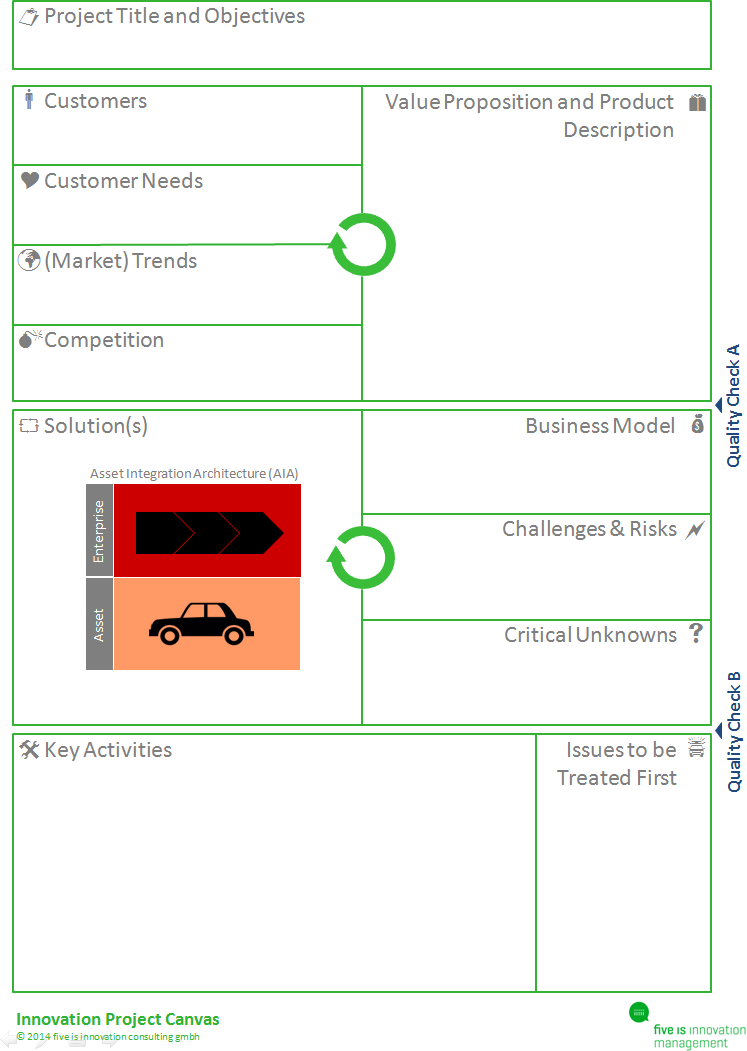

Another interesting tool for idea refinement is the Innovation Project Canvas developed by five i’s innovation management GmbH [IP1]. The Innovation Project Canvas is an extension of the original Osterwalder Business Model Canvas and has already been proven to be applicable for IoT concepts, such as in the field of smart home appliances, for example. Figure 1-3 provides an overview.

What is particularly useful about the Innovation Project Canvas is that it works in three phases. In the first, the interdisciplinary team focuses on possible customer groups, and on developing a compelling value proposition. The team refines the idea until convinced that it can offer significant benefit to the target group(s). In the second phase, the team discusses possible solutions that can deliver the value proposition and business model. Again, the result of this phase is revised and further improved.

Finally, in the third phase, an Agile development strategy is planned. The team identifies the most critical unknowns, or risks, and focuses on addressing these in the next phases of development.

The Innovation Project Canvas brings together all of the key members of a future project team in order to promote a common understanding of the project’s aims and content. The unified development of an attractive value proposition with a profitable business model quickly reveals the true potential of an idea, wins over enthused customers, and increases the commitment of the individual team members.

The output of the idea-refinement phase, the detailed idea sketch, can be used for presentations at the next quality gate level. After approval, it can be used to develop the business model.

Opportunity Qualification

At Bosch, the QuickScan method is used to qualify and select opportunities. Silke Vogel, Strategic Marketing Manager at Bosch Corporate, describes this method as follows:

The QuickScan method has been developed by the Web 3.0 core team members as means of quickly identifying promising business ideas leading to “the pot of gold.” The method focuses on three main criteria that are key in our view to creating success stories: market attractiveness, technological feasibility, and profitability. For all three main criteria, a specific set of subcriteria have been identified using five-point scales and detailed descriptions. In this way, all core team members evaluate the business ideas bilaterally, based on a common understanding, making the final scores of each business idea comparable to one other.

IoT Opportunity Management

Usually, after an idea has passed the first quality gate, a small team is assembled to further refine and validate the idea, with the goal of creating a concrete business case document that can attract funding. Typically, a small team works on an IoT business model for a couple of weeks or even months, before it is presented to the investment committee to decide on. If all IoT initiatives follow a similar IoT business model approach, it makes it easier to compare and prioritize the different proposals.

At Bosch, the project teams developing IoT business models include employees with multiple competencies, such as domain experts, business model coaches, and marketing consultants. Having both this organizational embedding, and a leader who is passionate about the idea from the start, is crucial. Another success factor is the structure of “podular” organizations. Silke Vogel explains what this means:

Highly motivated and energized team members join autonomous units. They have more decisive powers, can act in an “intrapreneurial” way, close to the customer, while also benefiting from the established structures and competencies of a large company. This makes them faster and more efficient.

Business Model Development

As established business model canvases don’t really address the specifics of IoT business models, a team at Bosch has worked on developing an IoT-specific approach to business model development. Veronika Brandt, manager of this team at Bosch Software Innovations:

Addressing IoT-specific aspects, like the intricacy of a partner ecosystem with complex value chains, is extremely important in the IoT. This means that the business model needs a clearly articulated partner value proposition. Another IoT-specific aspect is the use of data derived from connected things, and the services built on top of this information. Because of this, we have developed the IoT Business Model Builder—an extension of the Osterwalder canvas. In the Opportunity Management phase, it serves as a guide through the process of defining the components of the business model. Usually, the input is the formulated idea and the output is a business case.

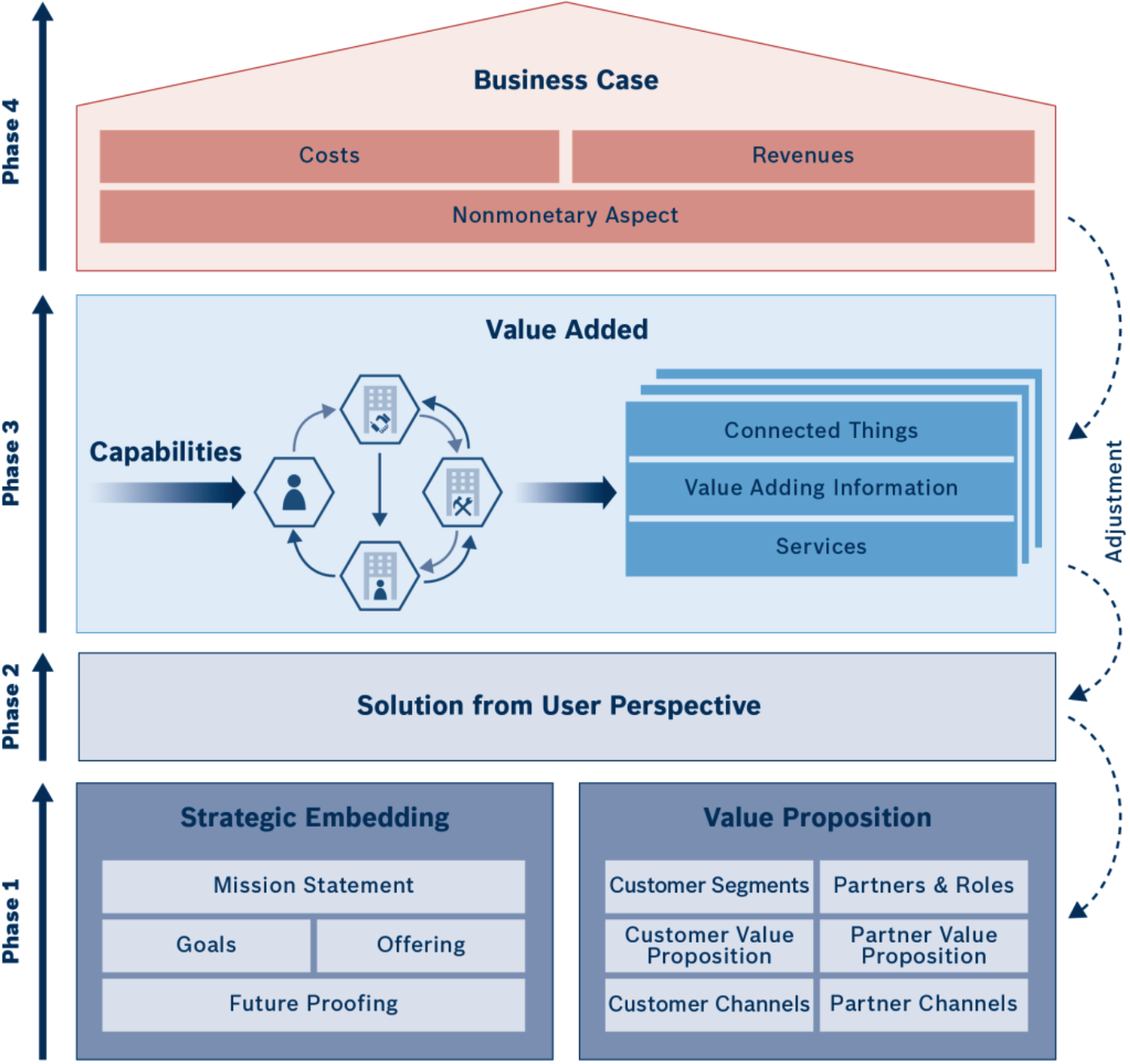

Figure 1-4 outlines the main components of the IoT Business Model Builder.

Just like when building a house, we start at the bottom:

- Strategic embedding

-

This phase sets the foundation of the business model and ensures alignment with the IoT strategy, or the IoT vision of the enterprise. It defines the purpose of the business model in the mission statement and outlines its mid- and short-term goals. Performing “future proofing” should indicate how the business model intends to deal with future challenges. This includes thoughts on how to foster the development of differentiators, such as core competencies (making it harder for the business model to be imitated) and responsiveness to future change. The strategic embedding also contains a brief description of the offering.

- Value proposition

-

To enhance the attractiveness of the offer for customers, the tried-and-trusted approach of segmenting target groups, formulating a value proposition, and defining customer channels (interfaces to the customer at all touch points in the customer journey, from awareness to after sales) can be employed. Because IoT solutions often depend on a strong partner ecosystem, the value proposition has to respect partners in the same way as customers. First, unless partners are not already named (e.g., by existing strategic partnerships or relations), their roles must be defined (e.g., information provider, broker, operator). Then, we need to define “what’s in it for them,” outlining the partner value proposition for each partner role (or candidate). Finally, the partner channels can be defined, as “other partners,” for example (it’s even possible for the customer to be defined as a channel).

- Customer journey

-

Describing the end-to-end solution from the customer’s point of view helps to emphasize the features of the offering that the customer finds relevant. Here, it is relevant to focus on the actual user/consumer of the offering, irrespective if this is your customer or the customer’s customer (in B2B2C solutions). Defining the customer journey has another positive side-effect: it makes sure all relevant channels to the customer have been identified, and these serve as customer touchpoints at every stage of the journey, from awareness to after sales.

- Value added

-

Once the solution has been defined, the value added can be illustrated. Core element of the value added is the stakeholder network, usually illustrated in a flowchart that visualizes relevant parties (own enterprise, partners, customers) as nodes, and value and service streams between these nodes. Constituting elements of the network are the capabilities of the parties: they are a mix of technology, resources, and know-how they can bring in to support the solution. The capability assessment helps define which nodes are best suited to deliver certain services. Once the network has been defined, it should be captured for each node what connected things this node is managing, which value-adding information it delivers (or derives from connected things), and which services it delivers.

- Business case

-

Once the value added has been defined, it is easy to calculate the business case: the most cost-relevant aspects are indicated in the value-added phase and the estimated revenue should be taken from the customer and partner value proposition. A relevant and fair approach is to calculate the total costs of ownership (TCO) for the solution across all parties involved in the network, and to then define the return model by allocating the returns among the stakeholders in a fair manner. This requires cost transparency across all parties involved, once again underlining the importance of trust and strategic partnerships in the IoT ecosystem. There are several techniques and templates that can be used for the business case calculation, but we recommend harmonizing one across all IoT initiatives, as this makes the business models easier to compare.

- Strategic impact and subsequent business models

-

The chimneys of the house in our diagram indicate two nonmonetary effects of a business model that should be looked at in conjunction with the business case. For example, if the business case does not look promising, but the company needs to implement the business model in order to enter a new market, or to access a new technology, these strategic aspects have to be documented. The second chimney, “subsequent business models,” is very specific to the IoT: when defining the business model and capturing all the data associated with connected devices, it is very common that the teams come up with interesting new ideas on how to leverage the data (e.g., by combining them to new value-adding information) and create new services. Some ideas are not leveraged within the same business model, but rather developed in separate business models. However, they need to refer to the business model that they are built upon.

Partner Ecosystem

The following advice on IoT partner ecosystem development comes from Anuj Jain, Director Partner Management by Bosch Software Innovations.

The IoT value chain is long and wide, encompassing physical assets, operational services, and digital services. Key considerations for IoT initiatives are:

-

What are the elements of the value chain that one can realistically deliver given the current capabilities?

-

How much of the control does one require on the IoT value chain ecosystem?

Practically, it is neither possible, nor reasonable, for any single player to specialize in all the aspects of the IoT value chain. For IoT initiatives, the right strategy is a partner ecosystem with a shared vision, passion, and objective. This allows ready access to specialist know-how and expertise at reasonable costs—an essential factor in the success of IoT projects. A well-crafted partner ecosystem accelerates the time to market, improves return on investment (ROI) for each stakeholder, and enhances the customer experience. It also assures customers that their investment will have continued support and innovation across the entire value chain.

Historically, only large, established behemoths like Daimler, Airbus, Microsoft, and IBM worked on building a partner ecosystem. In those cases, the “behemoth” was at the center of the ecosystem, typically wielding enormous influence and often defining the character of the ecosystem. IoT is popularizing an ecosystem of a value-adding network of partners and collaborative organizations that leads to competitive advantage. Both large companies and smaller players are successfully working on more diffused, less centralized ecosystems that arise organically and that lead to more equal and collaborative partners.

Let’s look at some popular examples of successful ecosystems:

-

Top of the mind is the example of Apple and the music industry. The music industry owned assets (music rights). Steve Jobs spotted the opportunity to provide a legal, affordable, and easy way to provide music to fans. Apple created a platform, and operated it well (operations services and digital services). Apple succeeded and controlled the ecosystem.

-

An exciting example is DriveNow. BMW manufactures great cars (physical assets). Sixt has extensive experience and competency in fleet operations and customer management (operational services). A concept to offer the cars on a more flexible basis was generated. Both organizations joined hands to develop a platform—DriveNow (digital services) to offer an innovative car-sharing service. Both partners are working at an eye level and significantly contributing to the partnership.

-

Another interesting ecosystem battle being played out at the moment concerns car infotainment. This is high-cost, high-margin equipment, traditionally controlled by OEMs. It allows a direct link to the customers that OEMs don’t want to lose. It’s about challenge and opportunity. Google and Apple enter with their connected services, disturbing the balance. Alignments are shaping up and the final stable ecosystem is yet to be established.

Customers are now looking for end-to-end solutions, not a collection of building blocks that they have to stick together. Customers expect open standards and interoperability. Customers require products and solutions that evolve with their operational needs. Currently we are just scratching the surface when it comes to possible uses of IoT technologies. It is expected that IoT solutions will continue to expand both horizontally and vertically to deliver even more value to the end customer. A partner ecosystem provides customers with access to a deep well of industry-specific knowledge and industry applications to address increasingly complex problems.

We encountered this situation recently, while working on a project to enhance digital and operational services for handheld industrial power tools (physical assets). Options were to keep this closed or confined, or to make it open standard and allow integration of any handheld power tools from any manufacturers. We opted for the latter and opened the platform further by successfully proposing to the Industrial Internet Consortium to make this a testbed for handheld industrial power tools. Bosch established an ecosystem together with Tech Mahindra, Cisco, Mongo DB, and Dassault Systems to bring the best of competencies to the overall solution.

The critical part of the ecosystem development journey is to identify the right partners. Such an ecosystem may work best if it’s based on revenue share vis-à-vis subcontractors. This is easier said than done, as each stakeholder carries a different perception of its contribution to the ecosystem. Mutual trust in ecosystem partners is very important. The ability to collaborate at the customer level (the most sacred thing in the business world) is a sign of a most valued partnership. The trust required for a joint go-to-market is significant as it not only demonstrates belief in each other’s products and expertise, but also that both parties trust the other to work toward a mutually beneficial outcome.

To return to our “clash of two worlds” discussion (which you’ll recall from not available), it’s important to identify what camp you belong to: the manufacturing camp or the Internet camp. How does this translate realistically into delivery capabilities and market access? Should we focus on core capabilities and allow organic development of an ecosystem? Or aim to play a significant (perhaps controlling) role in shaping the ecosystem? Where should we start here? Should we:

-

Define precise roles?

-

Establish a legal basis or a strategic partnership agreement?

-

Jointly develop new products?

-

Initiate joint marketing activities (press releases, thought leadership events, webinars, etc.)?

The IoT is still in its initial phase, it requires upfront investment, and cannot deliver immediate returns (in the next quarters or so), but instead lays the foundation for good long-term returns. For the most part, middle management (with short-term number orientation) find it difficult to manage this mismatch in expectations. Further, IoT project spans multiple verticals and horizontals. There is still lack of clarity about the group best suited to lead such initiatives, and many teams and individuals start politicking. Such partnerships require a significant involvement and commitment from the C level (and sometimes the board) in order to manage these complexities and provide direction.

Organizations don’t have enough time or money to waste on signing a bunch of agreements that just say “I love you; you love me.” Successful ecosystems involve high levels of trust, matching communication styles, and complementary skills. Extreme prudence is required for establishing such ecosystems.

Developing the IoT Business Case

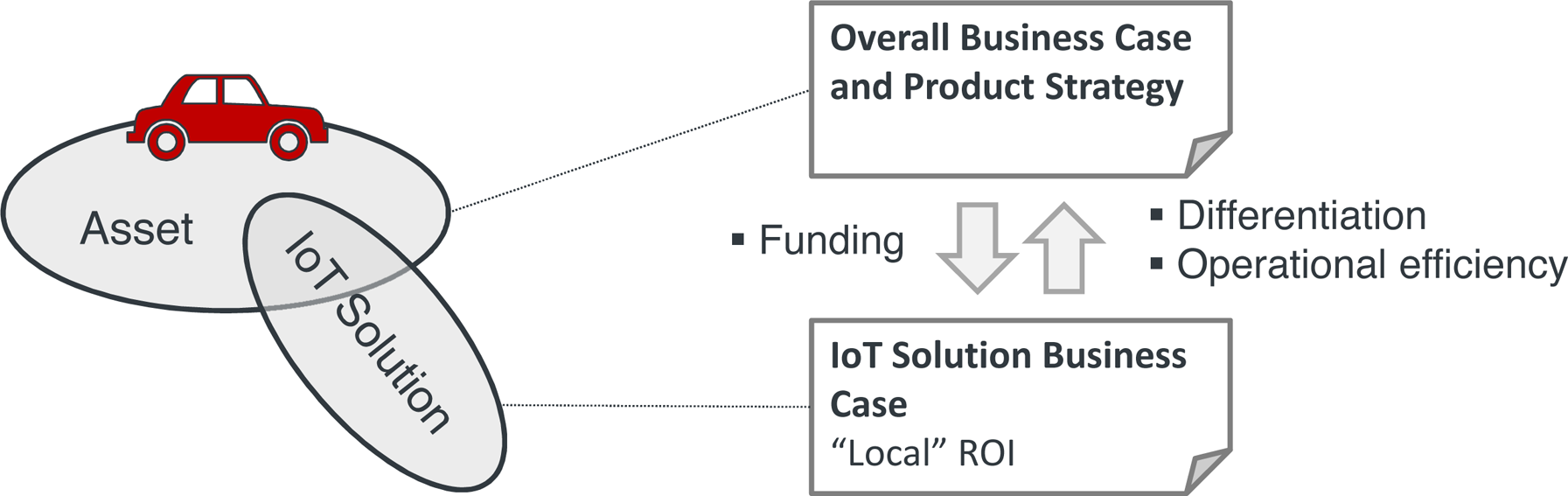

While it is important to understand all of the strategic aspects of the business model, many senior executives pay particular attention to the quantitative perspective—that is, the concrete business case (Figure 1-5).

Because business cases are always forward-looking, some managers take a cynical view of employees performing Excel-based exercises. However, most managers agree that these exercises are a good way to force the team to really think every aspect of the business model through in detail. Many budget discussions have been decided based not on the quality of the detailed business case calculation, but simply on the single number presented by the team as the result of this calculation. In this context, it is particularly important to understand the scope of the business case that is developed. Recall from not available our differentiation between the asset and IoT solution: it is absolutely critical to understand and communicate whether or not the business case relates to the overall asset or to the IoT solution only. Take the eCall example that we have used numerous times already: it is important to understand whether you are calculating a business case that says how much money you can make on the eCall service alone, or whether you are calculating how many more (or fewer) cars you will sell by being able to offer (or not offer) an eCall service. Keep in mind that the ROI of the “local IoT” solution will not always be positive. In many cases, the additional funding will be the “cost to compete” from the asset’s perspective.

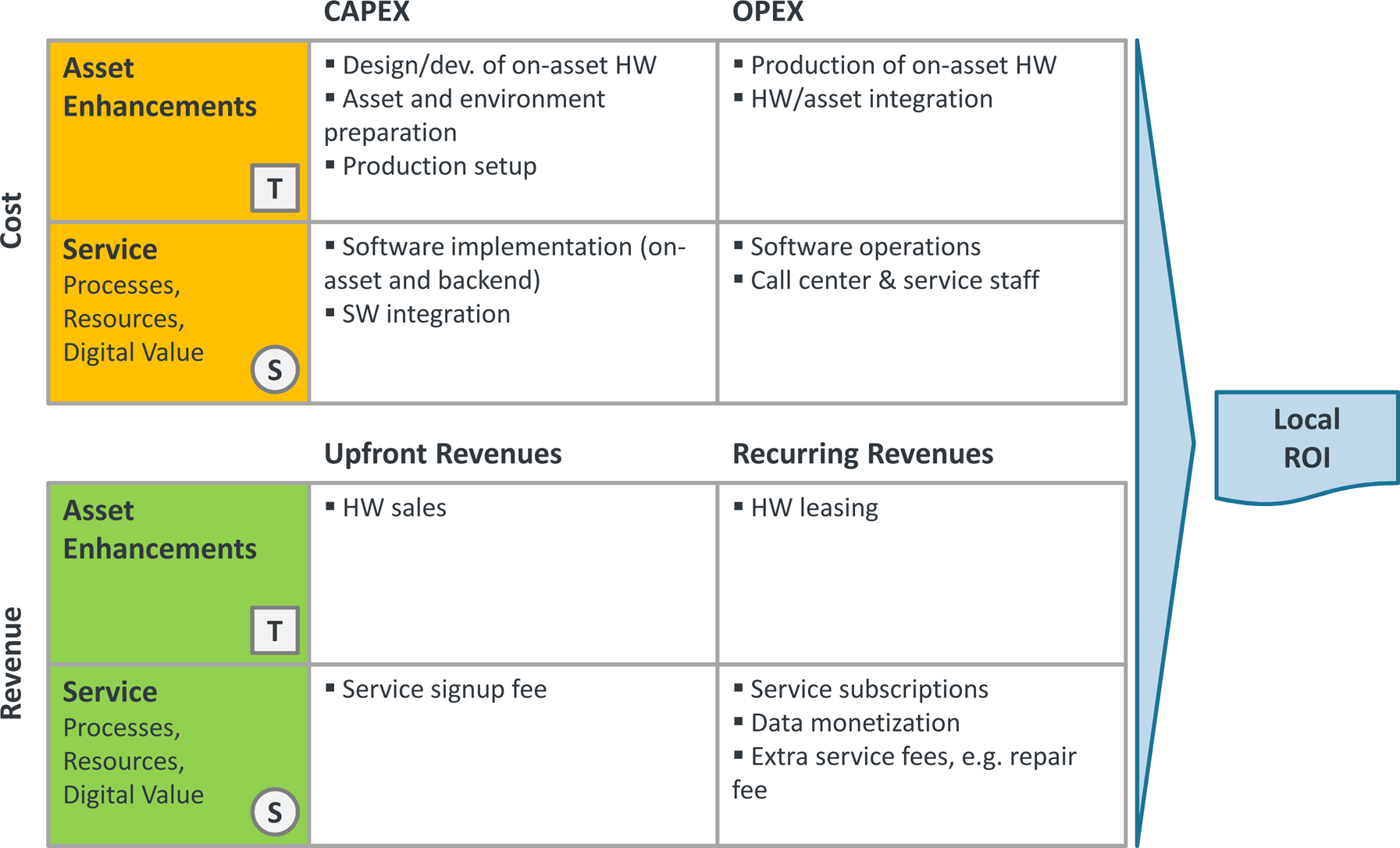

Let’s start by taking a more detailed look at the local ROI of an IoT solution. Figure 1-6 provides an overview of a generic IoT business case model. This model is based on the simple assumption that every IoT solution consists of a combination of asset enhancements (e.g., the on-asset hardware) and services that are implemented by leveraging the new connectivity to the asset. This service can be a fully automated IT service, or a human-operated service like a call center service (or both). So naturally, asset enhancement and service show up both on the cost and on the revenue side. On the cost side, we usually have to differentiate between capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operating expenditure (OPEX), while on the revenue side, we differentiate between up-front revenues (e.g., through hardware sales or a service sign-up fee) and recurring revenues (e.g., service subscriptions). Taking all of this together helps to calculate the “local” IoT solution ROI. It is really not rocket science, but in our experience it can be quite helpful when selling an IoT business case to visualize its key elements in a way similar to Figure 1-6.

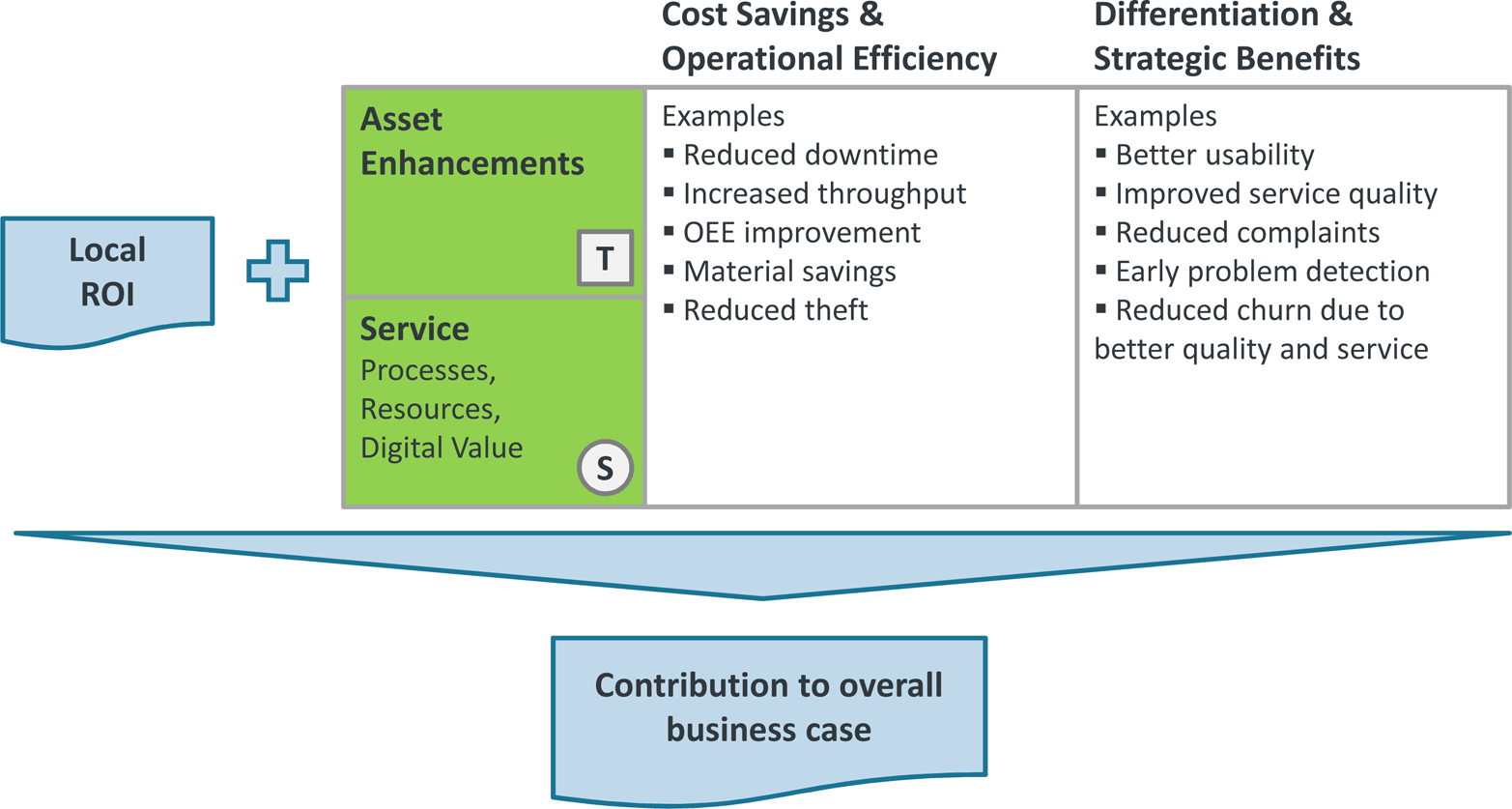

The next perspective is the overall business case, as shown in Figure 1-7. Again, this has to look at both asset enhancements and services. However, in this perspective we can also look at cost savings and operational efficiency on the one side, and differentiation and strategic benefits on the other.

In some cases, it will be possible to quantify this; in other cases, the case will have to be argued qualitatively. In either case, it is usually very useful to present these different aspects of the overall business case in a structured manner.

Business Case Challenges

Of course there are many challenges in the development of an IoT business case that are not obvious at first glance. Based on his experience, Felix Wortmann from the University of St. Gallen points out two major IoT business case challenges:

First of all, fixed costs for IoT hardware development should not be underestimated. While this is certainly not new to the traditional hardware community, people with a software background often think that new development methodologies and the latest advances in the context of Arduino and Raspberry Pi have fundamentally changed the laws and economics of hardware development. And yes, today first prototypes can often be realized on low budget hardware, for example, Arduino sets are available for less than $50. However, creating reliable hardware that can actually be deployed in the field still has very high associated costs. It is not only a question of initial design and prototyping. The investments required for testing and certification, and the cost for actually integrating IoT capabilities into existing hardware have to be taken into account as well. This means that from the very beginning, significant fixed costs that occur even before first revenue can be generated have to be considered. For this reason, there are significant risks involved. In addition, business models often rely on economies of scale to cope with fix costs and facilitate acceptable unit costs. To illustrate these thoughts, let’s take the example of a business case for a security solution for electronic bicycles. The initial assumption was that a sensor could simply be attached externally to the bicycle. However, digging deeper into the overall business case, it turned out that in order to provide a compelling use case, and also to achieve acceptable unit costs, this sensor has to be designed directly into the power train of the bike. This dramatically increases the initial investment and fundamentally affects the overall business case.

Secondly, IoT-enabled connected products require a backend infrastructure that generates operating costs on an ongoing basis. This is a fundamental difference compared to nonconnected products that do not generate costs after they have been sold. Thus, the operating costs of connected products have to be tackled. Either, they are calculated into the one-time sales price, or ongoing payments are introduced. However, pay-per-use or subscription-based models usually face severe customer acceptance challenges, specifically if hardware comes into play. Especially in the consumer context, people are often not willing to pay money for a physical object, connected or not, on an ongoing basis. This means that operating costs have to be calculated into the sales price. As a kind of risk insurance, companies use a variety of tactics, planned obsolescence, for example. Also, companies try to ensure that IoT-based products can still operate even if the provider shuts down its central infrastructure. Take, for example, the Philips Hue. This connected light bulb is designed to also work on the basis of a controlling local gateway, without the Philips backend. This effectively gives Philips the opportunity for a “graceful” exit strategy: If it would should down its own backend services, the customer has less functionality but the product still works.

These are just some examples for the complexity of IoT business cases, yet they illustrate why a structured process for their development can be helpful, and why they also take time to reach a certain level of maturity.

Impact and Risk Analysis

Business models, and especially business cases, deal with future value streams, so they are subject to uncertainty. It is important to highlight the degree of uncertainty within the business model to increase transparency for decision makers, and in order to deduce the tasks necessary to address these uncertain factors (e.g., if certain cost assumptions are very vague, it will be helpful to request proposals in the next step of the process to validate these estimations).

A helpful tool for reducing risk is scenario planning. Based on defined parameters (e.g., target group, time frame, etc., as assumed for the business model), different future scenarios are sketched out. This can be done based on trends or cause-and-effect relationships. In the next step, a plan has to be worked out to determine how the business model can best respond to the future scenario. It is important to explore those elements of the business model that generate impact and value in the context of a strategy. By acting out different future opportunities, weak points and strong elements can be revealed, which allows for the development of a future-proof business model.

Putting It All Together: The Business Plan

Having developed the business model, which can be based on the IoT Business Model Builder, the team needs to put together an actionable business plan. Of course, this will reuse many of the elements in the business model, but will have a stronger focus on execution planning. Sequoia Capital, one of the most respected venture capital firms in Silicon Valley, recommends the following approach for startups [SC1]:

- Purpose

-

Define the business in a single, declarative sentence.

- Problem

-

Describe the customer’s pain, and how he is coping with it today.

- Solution

-

Provide use cases to demonstrate how your solution addresses the customer’s problem. Describe where the product physically sits.

- Why now

-

Describe the historical evolution of your solution category. Describe factors that enable disruption today.

- Market size

-

Describe the total available market and the segment targeted by your solution based on a precise customer profile.

- Competition

-

Describe key competitors and compare competitive advantages.

- Solution

-

Describe form factor, functionality features, architecture and development roadmap, as well as key intellectual property.

- Business model

-

Revenue and pricing models, average account size and/or lifetime value, sales and distribution model, and description of current customer pipeline (if any).

- Team

-

Proposed organizational and management structure for the new business.

- Financials

-

Forward-looking (e.g., three years) profit and loss plan, balance sheet and cash flow plan, and funding requirements.

We have made some small changes to the original list from Sequoia Capital to ensure it fits the needs of an internal project. But in general, it seems to us like a good idea to follow the guidance of the “Internet camp” and apply it to an internal project proposal. Many companies will already have a standard template for project proposals that should at least be cross-checked with this structure.

Opportunity Selection

For the steering committee that will be presented with the business plans for the various IoT investment opportunities, the key question is: How should these different opportunities be evaluated and prioritized? In a corporate environment, there will always be a certain amount of political behind-the-scenes influencing, but it can be really helpful to map out the different opportunities and make them comparable, ideally on a single chart. It is important that the evaluation criteria be aligned with the overall IoT strategy, as defined at the beginning of this chapter.

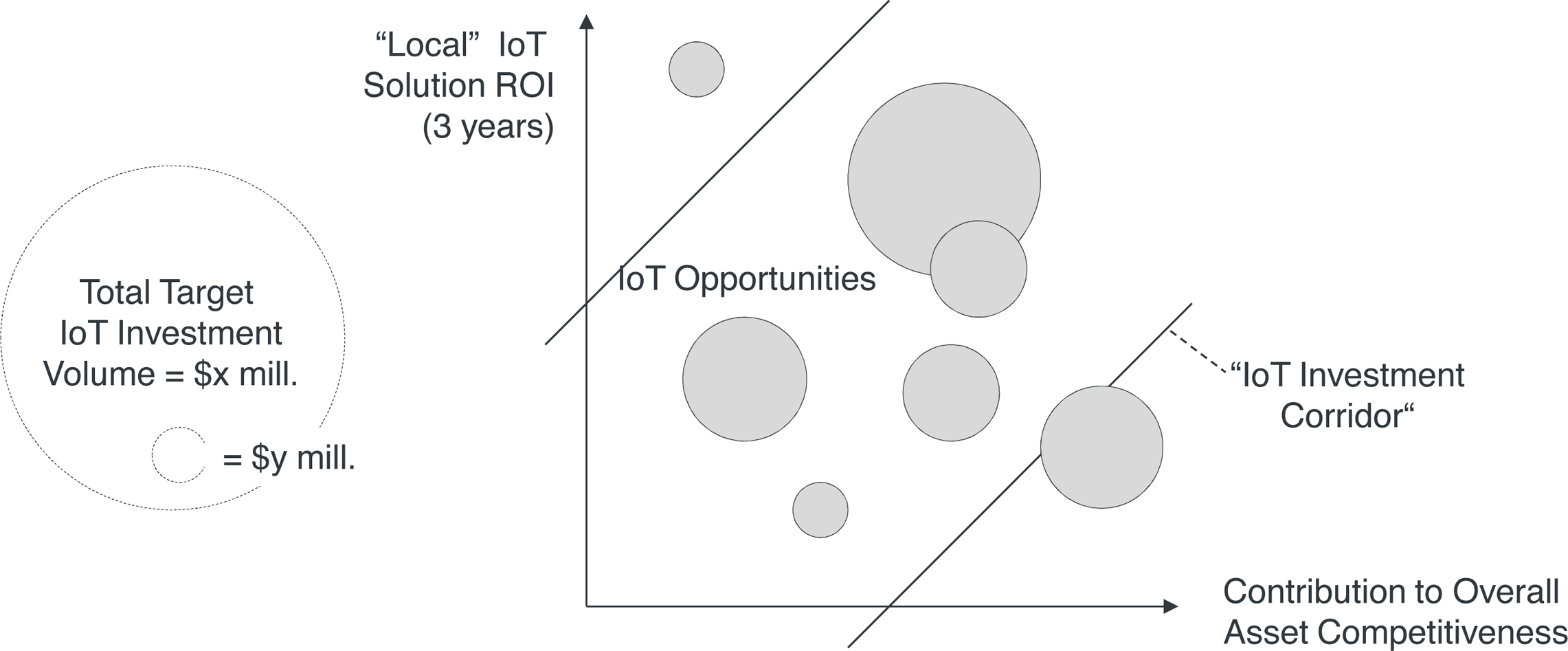

In the light of our previous discussion on the “local” business case versus the contribution of the new IoT solution to the overall competitiveness of the related asset, it would seem natural to pick these two perspectives as the key dimensions for an IoT portfolio evaluation chart, (Figure 1-8). Assuming that one would want to strike a good balance between these two dimensions, the chart should also define an “IoT investment corridor” that defines the area within which the investments should ideally be located. While the “ROI over a defined time period” (or some other economic measure, like economic value added, EVA) is usually easily quantifiable, the overall strategic contribution is usually harder to quantify.

Also, this needs to incorporate the overall value of the particular asset class to the company. A small strategic increase in value for the main asset that contributes 50% of the company’s revenues easily outweighs a huge strategic increase in value for a niche asset with low overall revenue contribution. Another important factor that is not included in this approach is market pressure—in other words, how critical is the timing of this investment?

It will always be difficult to create hard, reliable quantifications of these factors. Also, one should not underestimate the importance of the political power-plays and other factors that typically go along with corporate decision processes. However, the approach described here should help at least to create a certain level of transparency and objectification of the IoT investment decision process. And again, the end result might not be called “IoT investment evaluation chart” but something more vertically specific, like “Connected vehicle opportunity evaluation chart,” or some such. But the basic principles should apply.

Project Initiation

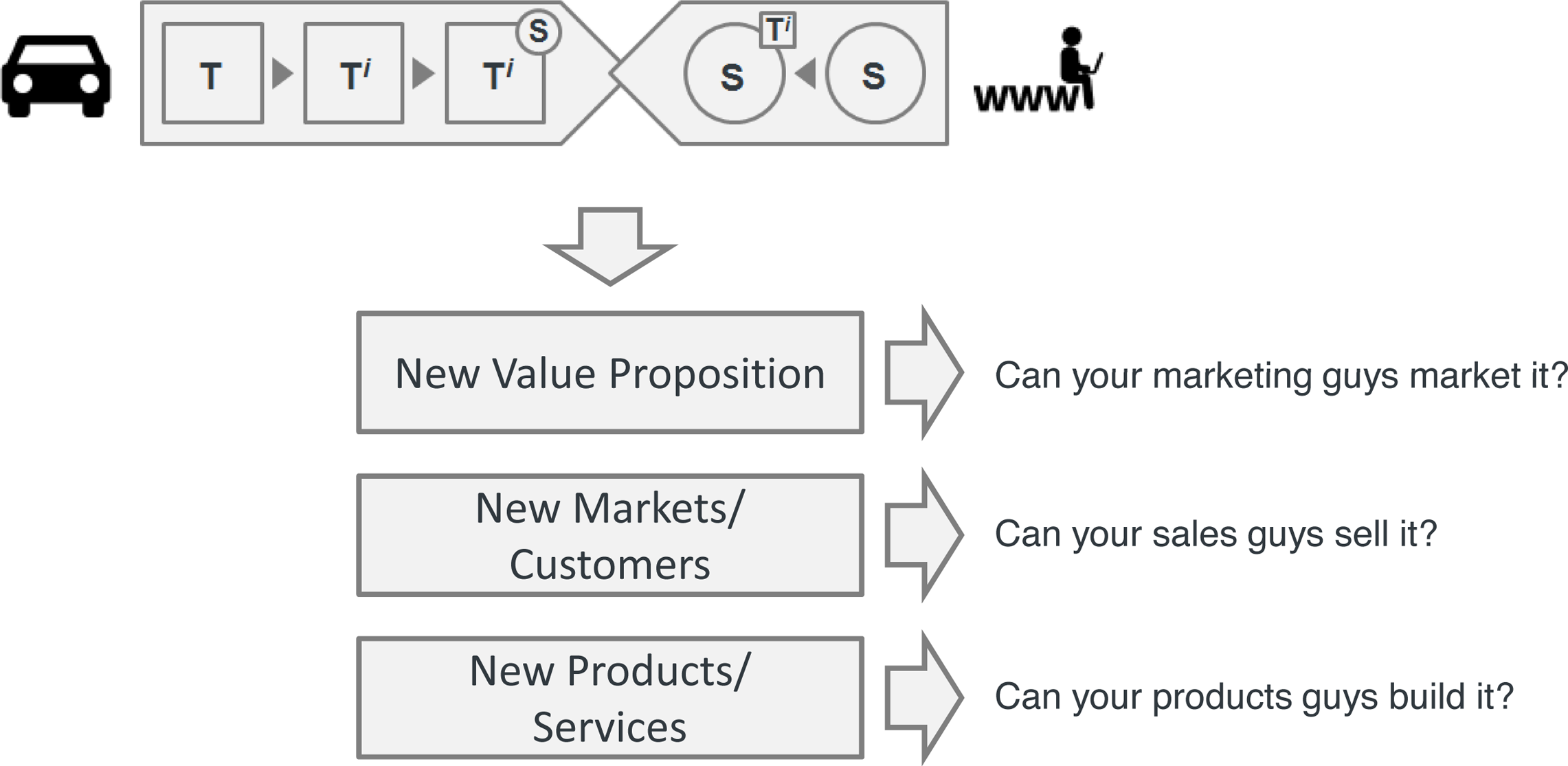

What usually happens in parallel to the development of the detailed business plan is an evaluation of the ideal organizational setup and execution strategy. In addition to the important time-to-market factor, one has to look critically at internal execution capabilities (Figure 1-9). Again, this comes back to the “machine camp” versus “Internet camp” discussion from not available. Which direction are we coming at this from? And where do we need to end up? Will we be able to develop the required culture and capabilities internally?

Based on these kinds of questions, the steering committee will have to make a decision about the best way of managing each IoT opportunity. Typical options include internal projects, external acquisitions, or spin-offs. Also quite common is a mixture of these—that is, to set up an entity that consists in one part of people with strong roots in the larger enterprise, and another part of people that came in through acquisitions. Also, the term “acqui-hiring” has become popular recently, describing a strategy of acquiring companies, less for their products and customer base than for their team and talent.

Careful attention must be paid to organizational setup, especially for IoT opportunities that are developed by leveraging existing internal organization. In particular, the interfaces and relationships between the solution team and the existing asset organization are essential.

At Bosch, there are more and more cases where “podular” organizations are set up on the business unit level as well. “It is easier, if there is already a home port for the ideas within the organization,” says Ms. Silke Vogel. “This way, the employees, who have worked on the idea refinement and business model development, can drive the projects in the execution phase as well.”

IoT Center of Excellence

If the company sees IoT as a long-term transformation, then setting up an IoT Center of Excellence (CoE) should be considered to guide and expedite this transformation. Based on the description of the typical functions of a CoE [AE1], an IoT CoE could look as follows:

- Support

-

An IoT CoE should support business lines to realize IoT opportunities through the provision of IoT consulting services. These services can include IoT business case creation, IoT project setup, and IoT project execution coaching. As authors of this book, we are slightly biased, but we would naturally recommend the Ignite | IoT Methodology as one possible foundation for such services.

- Guidance

-

An IoT CoE should help to define the necessary standards, methodologies, tools, and knowledge repositories. Some of these will be highly vertical-specific. However, best practices for setting up things like a remote communication infrastructure for mobile assets could be standardized (see not available for examples).

- Shared learning

-

Training and certifications, skill assessments, team building, and formalized roles are all established methods that can be applied to developing IoT capabilities.

- Measurements

-

An IoT CoE should create IoT-specific metrics and maturity models that help make the progress of the transformation more transparent.

- Governance

-

They should support the steering committee with the cross-project coordination and other detailed governance tasks. Especially in the connected IoT world, there will always be many cross-dependencies between projects that need to be managed carefully.

Naturally, running a dedicated IoT CoE will be a significant investment, and many companies report mixed results from their other CoE initiatives. It is important that the CoE is seen by the projects as value-adding, and not as a disturbance. There are usually two options for the setting up of the CoE: a dedicated CoE resource, or a virtual CoE with members who are embedded in operational teams but are allowed to spend a certain percentage of their time in supporting the CoE. The latter has the advantage that the CoE experts are coming from a hands-on project background with a lot of experience, but has the disadvantage that these highly respected experts are often drowned in project work and can’t really fulfill their part-time CoE role as much as needed.

IoT Platform

Finally, enterprises embarking on the IoT journey should consider investing in the setup and operation of an IoT platform that can be shared by the different IoT projects. Such a platform could be comprised of the following:

-

Remote asset connectivity—for example, based on the M2M platform of a telecommunications carrier or a mobile virtual network operator (MVNO; see not available)

-

IoT application development and runtime (see not available)

-

IoT data management infrastructure (see not available)

-

IoT security infrastructure—for example, central identity and certificate management (see not available)

-

Standards—for example, for communication protocols and the like

-

Asset interface repository—for example, a central wiki to describe the functional and technical interfaces of different device and asset types that play an important role in the organization

Theoretically, providing such an IoT platform should be seen as a blessing by everybody needing to get a project off the ground quickly. However, we should definitely be aware of the inherent risks of such a central platform approach. One of these is that the platform might actually not work (e.g., because it is over-architected and not field-tested). Or it might not be ready on time. Or it might be inefficient and too difficult to operate. These are just some of the real risks involved in developing a central platform. On the other hand, if this needs to be done for each individual project, there is also a real risk that the project team won’t get it right half the time. So the sensible thing to do would be to observe those initial projects that seem to be developing the best platform approach, and then identify the parts of these projects that can be generalized. So it really is a question of maturity and timing.

Summary and Conclusions

As we explained at the start, some of the processes and methods described here are very generic and need to be adapted to the vertical needs and specific circumstances of the individual organization. For some companies, the elaborate way of developing a detailed business model as described here may seem like overkill. However, we have seen many examples where such business model development took significant time and many iterations—especially for solutions that need to be embedded into existing, large-scale, complex ecosystems.

Particular attention needs to be paid to the organizational structure of the project. IoT projects almost always require multiskilled and multicultural teams. Aligning the “machine camp” with the “Internet camp” is a challenging task. One possible approach is described as follows by Joe Drumgoole, Director at MongoDB, Inc.:

The Internet of Things provides a framework for both these communities to interact. If [large players] can create a bridge between those worlds, they will be successful, but I think success will come in the context of early wins with a small number of partners. Lead with the Internet people and use them as a foil to provoke the manufacturing people into action.

Another important thing to consider is that business plans for early-stage startups or projects rarely survive the first year without major modifications. So supporting an Agile (this does not mean unstructured or uncontrolled!) development approach will be a key success factor for most IoT initiatives. We will address this in more detail in the next chapter, the Ignite | IoT Solution Delivery methodology. This methodology is designed to support the next phase for those IoT projects that have managed to come through the strategy selection process with sufficient funding to start implementing their ideas and vision.