Introduction to OKRs

Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) have helped organizations like Google and LinkedIn achieve their goals. Learn what OKRs are and how to apply them to your business.

Tightwire walker on the Three Gossips. (source: John Menard on Flickr)

Tightwire walker on the Three Gossips. (source: John Menard on Flickr)

Introduction

Why is there so much interest in Objectives and Key Results, or OKRs? After all, OKRs are just a goal-setting methodology. When Silicon Valley startups discovered OKRs were behind the meteoric rise of companies such as Google, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Zynga, company after company decided to adopt OKRs, hoping to catch even a fraction of that success. But they struggled. The knowledge of how to use OKRs effectively was lore, passed on from employees who often had a partial understanding of how and why they worked. Many companies failed to use them successfully and then abandoned them with the same alacrity with which they adopted them.

There is no question that OKRs work. The mystery is why they don’t work for everyone. This report will share how the best companies use them to create focus, unity, and velocity.

OKR is an acronym, and like most acronyms, the words behind the letters are often forgotten. This is a deadly mistake. The words behind the acronym are where the power of the simple system lies. O stands for objective. What do you want your company to achieve? KR stands for key results. How would you measure that objective if you made it? What numbers would move?

Is your objective to create a thriving business? What do you mean by thriving? Growing your user base? By how much? Revenues climbing? By how much? Retention? For how long? The combination of the aspirational objective and quantitative results creates a goal that is both inspiring and measurable. It’s a SMART goal, but also short and clear enough that every employee can remember it and make decisions by it.

A great goal is a powerful tool, but it’s not enough. A leader needs a way to ensure that her organization lives that goal. The real power of the OKR system is figuring out how to live that goal every day, as a team. OKRs are best achieved if they are baked into the daily and weekly cadence of a company, from planning meetings and status emails.

An Extremely Short History of OKRs

Since the rise of “management science” in the 1950s, business leaders have embraced a variety of techniques designed to improve their company’s performance. Peter Drucker introduced Management by Objectives (MBOs), a process during which management and employees define and agree upon objectives and what they need to do to achieve them.

MBOs are the clear forerunner of Objectives and Key Results (OKRs). The idea that a manager would set an objective and then trust his team to accomplish it without micromanaging them was a huge and efficient shift from the more controlling approaches of the industrial age. In many ways, it was the first management philosophy truly aligned with the new information age.

In the early 1980s, SMART goals, developed by George T. Doran, and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) became popular methods for organizations to set objectives. KPIs introduced metric-validated performance evaluation for companies. There is an old joke in advertising that “Half our advertising is working. I just don’t know which half.” But the rise of the Internet and data science changed all that. Now, it was possible to know what was working and learn what caused those KPIs to grow.

SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Results-focused, and Time-bound. Elements of this approach went into OKRs, particularly results-focused and time-bound.

In 1999, John Doerr introduced the OKRs goal-setting methodology to Google, a model he first learned about at while he was at Intel.

I was first exposed to OKRs at Intel in the 1970s. At the time, Intel was transitioning from a memory company to a microprocessor company, and Andy Grove and the management team needed employees to focus on a set of priorities in order to make a successful transition. Creating the OKR system helped tremendously and we all bought into it. I remember being intrigued with the idea of having a beacon or north star every quarter, which helped set my priorities. It was also incredibly powerful for me to see Andy’s OKRs, my manager’s OKRs, and the OKRs for my peers. I was quickly able to tie my work directly to the company’s goals. I kept my OKRs pinned up in my office and wrote new OKRs every quarter, and the system has stayed with me ever since.

In Grove’s famous management manual High Output Management (Penguin Random House, 1995), he introduces OKRs by answering two simple questions: 1) Where do I want to go? and 2) How will I know I’m getting there? In essence, what are my objectives, and what key results do I need to keep tabs on to make sure I’m making progress? And thus OKRs were born.

From Google and Zynga—companies Doerr both invested in and advised—the OKR goal-setting methodology has spread to LinkedIn, GoPro, Flipboard, Spotify, Box, Paperless Post, Eventbrite, Edmunds.com, Oracle, Sears, Twitter, GE, and more.

What Are OKRs?

The acronym OKR stands for Objective and Key Results. The Objective is qualitative, and the Key Results (most often three) are quantitative. They are used to focus a group or individual on a bold goal. The Objective establishes a goal for a set period of time, usually a quarter. The Key Results indicate whether the Objective has been met by the end of the time.

Objectives

Your Objective is a single sentence that is:

- Qualitative and inspirational

-

The Objective is designed to get people jumping out of bed in the morning with excitement. And while CEOs and VCs might jump out of bed in the morning with joy over a three percent gain in conversion, most mere mortals get excited by a sense of meaning and progress. Use the language of your team. If they want to use slang and say “pwn it” or “kill it,” use that wording.

- Time-bound

-

For example, something that is achievable in a month or a quarter. You want it to be a clear sprint toward a goal. If it takes a year, your Objective might be a strategy or maybe even a mission.

- Actionable by the team independently

-

This is less a problem for startups, but bigger companies often struggle because of interdependence. Your Objective has to be truly yours, and you can’t have the excuse of “Marketing didn’t market it.”

Pusher, a startup using OKRs to accelerate its growth in the API as a service business, writes about its first OKR retrospective (“How We Make OKRs Work”):

We learned things like:

Don’t create objectives that rely on the input of other teams unless you’ve agreed with them that you share priorities.

Don’t create objectives that will require people we haven’t hired yet!

Be realistic about how much time you will have to achieve your goals.

An Objective is like a mission statement, only for a shorter period of time. A great Objective inspires the team, is hard (but not impossible) to do in a set time frame, and can be done by the person or people who have set it, independently.

Here are some good Objectives:

-

Own the direct-to-business coffee retail market in the South Bay.

-

Launch an awesome MVP.

-

Transform Palo Alto’s coupon-using habits.

-

Close a round that lets us kill it next quarter.

And here are some poor Objectives:

-

Sales numbers up 30 percent.

-

Double users.

-

Raise a Series B of $5 million.

Why are those bad Objectives bad? Probably because they are actually Key Results.

Key Results

Key Results take all that inspirational language and quantify it. You create them by asking a couple of simple questions:

How would we know if we met our Objective? What numbers would change?

This forces you to define what you mean by “awesome,” “kill it,” or “pwn.” Does “killing it” mean visitor growth? Revenue? Satisfaction? Or is it a combination of these things?

A company should have about three Key Results for an objective. Key Results can be based on anything you can measure. Here are some examples:

-

Growth

-

Engagement

-

Revenue

-

Performance

-

Quality

That last one can throw people. It seems hard to measure quality. But with tools like Net Promoter Score (NPS), you can do it. NPS is a number based on a customer’s willingness to recommend a given product to friends and family. (See “The Only Number You Need to Grow”. Harvard Business Review, December 2003.)

If you select your KRs wisely, you can balance forces like growth and performance, or revenue and quality, by making sure you have the potentially opposing forces represented.

In Work Rules!, Laszlo Bock writes:

It’s important to have both a quality and an efficiency measure, because otherwise engineers could just solve for one at the expense of the other. It’s not enough to give you a perfect result if it takes three minutes. We have to be both relevant and fast.

As an Objective, “Launch an awesome MVP” might have KRs like the following:

-

Forty percent of users come back two times in one week

-

Recommendation score of eight

-

Fifteen percent conversion

Notice how hard those are?

KRs should be difficult, not impossible

OKRs always stretch goals. A great way to do this is to set a confidence level of 5 of 10 on the OKR. By confidence level of 5 out of 10, I mean, “I have confidence I only have a 50/50 shot of making this goal.” A confidence level of one means, “It would take a miracle.”

As you set the KR, you are looking for the sweet spot where you are pushing yourself and your team to do bigger things, yet not making it impossible. I think that sweet spot is when you have a 50/50 shot of failing.

A confidence level of 10 means, “Yeah, gonna nail this one.” It also means you are setting your goals way too low, which is often called sandbagging. In companies where failure is punished, employees quickly learn not to try. If you want to achieve great things, you have to find a way to make it safe for your employees to aim higher and to reach further than anyone has before.

Take a look at your KRs. If you are getting a funny little feeling in the pit of your stomach saying, “We are really going to have to all bring our A game to hit these,” you are probably setting them correctly. If you look at them and think, “We’re doomed,” they’re too hard. If you look them and think, “I can do that with some hard work,” they are too easy.

Why Use OKRs?

Ben Lamorte, founder of okrs.com, tells this story:

My mentor and advisor, Jeff Walker, the guy who introduced me to OKRs, once asked me, “When you go on a hike, do you have a destination?” I paused since I was not sure where Jeff was going with this, so Jeff picked up, “When you hike with your family in the mountains, it’s fine if you like to just walk around and see where you go, but when you’re here at work, you need to be crystal clear about the destination; otherwise, you’re wasting your time, my time, and the time of everyone who works with you.

Your OKRs set the destination for the team so no one wastes their time.

OKRs are adopted by companies for one of three key reasons:

- Focus

-

What do we do and what do we not do as a company?

- Alignment

-

How do we make sure the entire company focuses on what matters most?

- Acceleration

-

Is your team really reaching its potential?

Focus

At Duxter, a social network for gamers, the team adopted OKRs to solve a classic startup problem: shiny object syndrome. CEO Adam Lieb writes:

Like all startups we struggle with priorities. Possibly the most used/overused saying at Duxter is “bigger fish to fry.” We had two big “fish problems.” The first was having competing views of which fish we should be frying. Often times, these drastically different views caused conflict and inefficiency.

The second was that our biggest fish seemed to change on a weekly or even daily basis. It became more and more difficult to keep everyone in the company apprised of where their individual focus should be.

Instituting OKRs have helped significantly with both of these problems.

Alignment

In an interview, Dick Costolo, former Googler and former CEO of Twitter, was asked what he learned from Google that he applied to Twitter. He shared the following:

The thing that I saw at Google that I definitely have applied at Twitter are OKRs—Objectives and Key Results. Those are a great way to help everyone in the company understand what’s important and how you’re going to measure what’s important. It’s essentially a great way to communicate strategy and how you’re going to measure strategy. And that’s how we try to use them. As you grow a company, the single hardest thing to scale is communication. It’s remarkably difficult. OKRs are a great way to make sure everyone understands how you’re going to measure success and strategy.

OKRs are more effective at uniting a company than KPIs because they combine qualitative and quantitative goals. The Objective, which is inspiring, can fire up employees who might be less metrics-oriented, such as design or customer service. The KRs bring the point home for the numbers-driven folks like accounting and sales. Thus, a strong OKR set can unite an entire company around a critical initiative.

Acceleration

From Re:Work, Google’s official guide to OKRs:

Google often sets goals that are just beyond the threshold of what seems possible, sometimes referred to as “stretch goals.” Creating unachievable goals is tricky as it could be seen as setting a team up for failure. However, more often than not, such goals can tend to attract the best people and create the most exciting work environments. Moreover, when aiming high, even failed goals tend to result in substantial advancements.

The key is clearly communicating the nature of stretch goals and what the thresholds for success are. Google likes to set OKRs such that success means achieving 70 percent of the objectives, while fully reaching them is considered extraordinary performance.

Such stretch goals are the building blocks for remarkable achievements in the long term, or “moonshots.”

Because OKRs are always stretch goals, they encourage employees to continually push the envelope. You never know what you are capable of until you shoot for the moon.

That said, this is the trickiest aspect of OKRs. But, while we’re talking about moonshots, let me use a Star Trek metaphor.

Scottie always implored, “The engines can’t take it anymore.” Yet somehow he always pulled a miracle out of his hat and made the engines perform anyway.

Geordie would say, “You have five minutes before the engines give out,” and five minutes later the engines would give out. If he knew of a way around it, he’d tell you, but you knew what was going on and could plan for it.

As a captain, do you want someone who likes to be a hero or someone who knows what the company can actually do? I know what kind of captain I’d like to be.

If you tie OKRs to performance reviews and bonuses, employees will always underestimate what they can do. It’s too dangerous to aim high, because what if you are wrong? But if you encourage bold OKRs and then carry out your review based on actual performance, employees are rewarded based on what they do, not how well they lie.

After all, on the way to the moon, sometimes we get Tang, Sharpies, and Velcro. Isn’t that worth rewarding?

Living Your OKRs

Many companies who try OKRs fail, and they blame the system. But no system works if you don’t actually keep to it. Setting a goal at the beginning of a quarter and expecting it to magically be achieved by the end is naïve. It’s important to have a cadence of commitment and celebration.

Scrum is a technique used by engineers to commit to progress and hold each other both accountable and to support each other. Each week an engineer shares what happened last week, explains what she commits to do in the upcoming week, and points out any blockers that might keep her from her goals. In larger organizations, they hold a “scrum of scrums” to assure that teams are also holding each other accountable for meeting goals. There is no reason multidisciplinary groups can’t do the same.

Monday Commitments

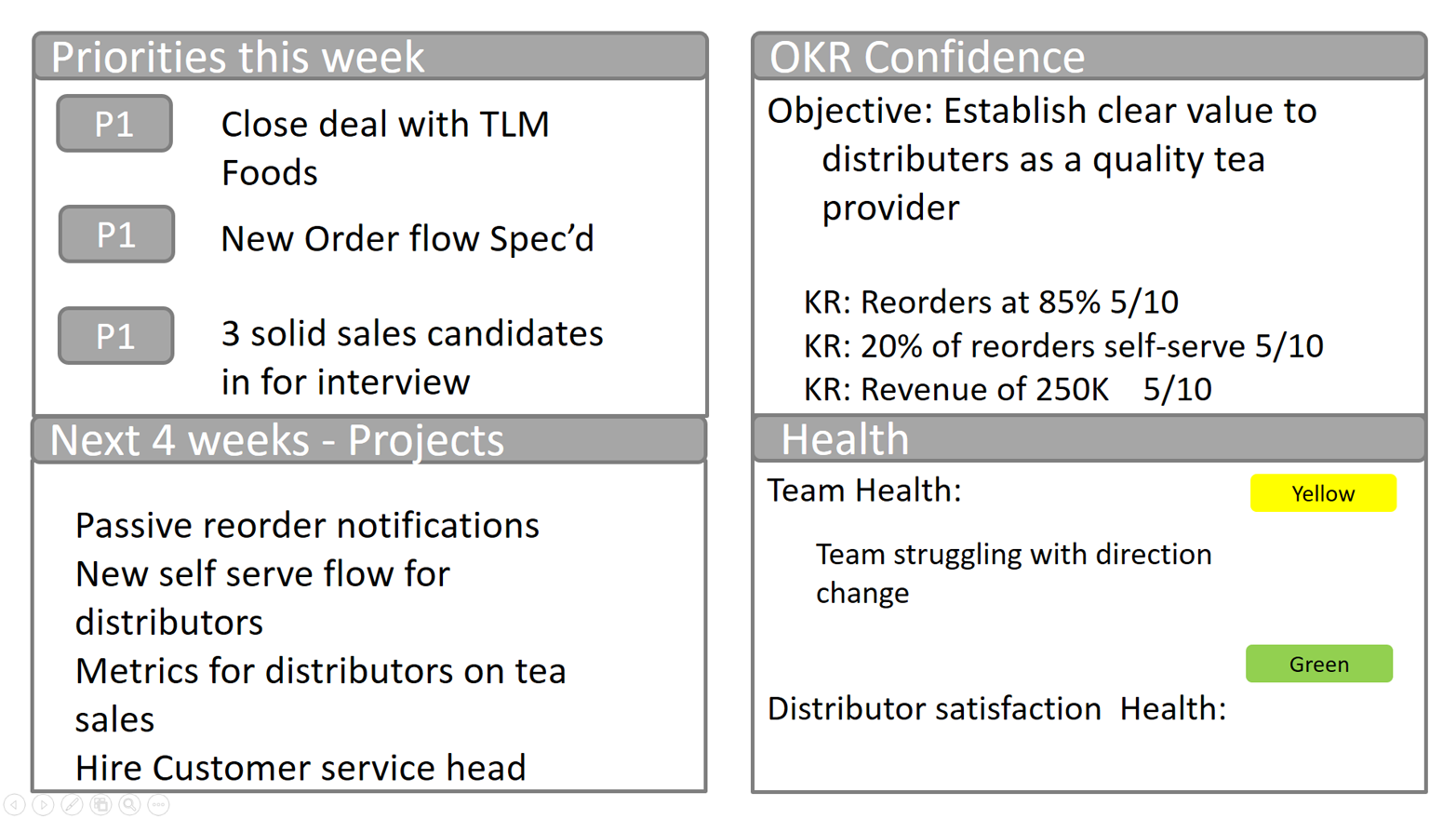

Each Monday, the team should meet to check in on progress against OKRs, and commit to the tasks that will help the company meet its Objective. I recommend a format with four key quadrants (see Figure 2-1):

- Intention for the week

-

What are the three to four most important things you must get done this week toward the Objective? Discuss whether these priorities will get you closer to the OKRs.

- Forecast for month

-

What should your team know is coming up that it can help with or prepare for?

- Status toward OKRs

-

If you set a confidence of 5 out of 10, has that moved up or down? Have a discussion about why. Are there any blockers endangering your OKRs?

- Health metrics

-

Pick two things that you want to protect as you strive toward greatness. What can you not afford to mess up? Key relationships with customers? Code stability? Team well-being? Now mark when things start to go sideways and discuss it.

This document is first and last a conversation tool. You want to talk about issues like these:

-

Do the priorities lead to our hitting our OKRs?

-

Why is confidence dropping in our ability to make our OKRs? Can anyone help?

-

Are we prepared for major new efforts? Does Marketing know what Product is up to?

-

Are we burning out our people or letting hacks become part of the code bases?

When you meet, you could discuss only the four-square (Figure 2-1), or you can use it to provide a status overview and then supplement with other detailed documents covering metrics, a pipeline of projects, or related updates. Each company has a higher or lower tolerance for status meetings.

Try to keep things as simple as possible. Too many status meetings are about team members trying to justify their existence by listing every little thing they’ve done. Trust that your team makes good choices in their everyday lives. Set the tone of the meeting to be about team members helping each other to meet the shared goals to which they all have committed.

Have fewer priorities and shorter updates.

Make time for the conversations. If only a quarter of the time allotted for the Monday meeting is presentations and the rest is discussing next steps, you are doing it right. If you end early, it’s a good sign. Just because you’ve set aside an hour doesn’t mean you have to use it.

Jeff Weiner, CEO of LinkedIn, does things a little differently. He opens his staff meeting with “wins.” Before delving into metrics or the business at hand, he goes around the room and asks each of his direct reports to share one personal victory and one professional achievement from the previous week. This sets up a mood of success and celebration before dicing into hard talks about why one key result or another might be slipping.

Fridays Are for Winners

When teams are aiming high, they fail a lot. Although it’s good to aim high, missing your goals without also seeing how far you’ve come is often depressing. That’s why committing to the Friday wins session is so critical.

In the Friday wins session, teams all demonstrate whatever they can. Engineers show bits of code they’ve got working, and designers show mockups and maps. Every team should share something. Sales can talk about who they’ve closed, Customer Service can talk about customers they’ve rescued, Business Development shares deals. This has several benefits. One, you begin to feel like you are part of a pretty special winning team. Two, the team begins looking forward to having something to share. They seek wins. And lastly, the company begins to appreciate what each discipline is going through and understands what everyone does all day.

Providing beer, wine, cake, or whatever is appropriate to your team on a Friday is also important to making the team feel cared for. If the team is really small and can’t afford anything, you can have a “Friday Wins Jar” to which everyone contributes. But as the team becomes bigger, the company should pay for the celebration nibbles as a signal of support. Consider this: the humans who work on the project are the biggest asset. Shouldn’t you invest in them?

OKRs are great for setting goals, but without a system to achieve them, they are as likely to fail as any other process that is in fashion. Commit to your team, commit to each other, and commit to your shared future. And renew those vows every week.

How to Hold a Meeting to Set OKRs for the Quarter

Setting OKRs is hard. It involves taking a close look at your company, and it involves having difficult conversations about the choices that shape the direction the company should go. Be sure to structure the meeting thoughtfully to get the best results. You will be living these OKRs for the next quarter.

Keep the meeting small—10 or fewer people if possible. It should be run by the CEO, and must include the senior executive team. Take away phones and computers. It will encourage people to move quickly and pay attention.

A few days before the meeting, solicit all of the employees to submit the Objective they think the company should focus on. Be sure to give them a very small window to do it in; 24 hours is plenty. You don’t want to slow down your process and, in a busy company, later means never.

Have someone (a consultant, the department heads) collect and bring forward the best and most popular Objectives.

Set aside four and a half hours to meet: two 2-hour sessions, with a 30-minute break between.

Your goal: cancel the second session. Be focused.

Each executive head should have an Objective or two in mind to bring to the meeting. Have the best employee-generated Objectives written out on Post-it notes, and have your executives add theirs. I recommend having a variety of sizes available, and use the large ones for the Objectives. Cramped writing is difficult to read.

Now, have the team place the Post-its up on the wall. Combine duplicates, and look for patterns that suggest people are worried about a particular goal. Combine similar Objectives. Stack rank them. Finally, narrow them down to three.

Discuss. Debate. Fight. Stack. Rank. Pick.

Depending on the team you have, you have either hit the break or you have another hour left.

Next, have all of the members of the executive team freelist as many metrics as they can think of to measure the Objective. Freelisting is a design-thinking technique. It means to simply write down as many ideas on a topic as you can, one idea per Post-it. You put one idea on each Post-it so that you can rearrange, discard, and otherwise manipulate the data you have generated (see Figure 3-1).

It is a far more effective way to brainstorm, and it results in better and more diverse ideas. Give the team slightly more time than is comfortable, perhaps 10 minutes. You want to get as many interesting ideas as possible.

Next, you will affinity map them. This is another design-thinking technique. All it means is that you group Post-its with like Post-its. If two people both write daily active users (DAU), you can put those on top of each other. It’s two votes for that metric. DAU, MAU, and WAU are all engagement metrics, and you can put them next to one another. Finally, you can pick your three types of metrics.

Write the KRs as an X first; that is, “X revenue” or “X acquisitions” or “X DAU.” It’s easier to first discuss what to measure than what the value should be and if it’s really a “shoot for the moon” goal. One fight at a time.

As a rule of thumb, I recommend having a usage metric, a revenue metric, and a satisfaction metric for the KRs; however, obviously that won’t always be the right choice for your Objective. The goal is to find different ways to measure success, in order to have sustained success across quarters. For example, two revenue metrics means that you might have an unbalanced approach to success. Focusing only on revenue can lead to employees gaming the system and developing short-term approaches that can damage retention.

Next, set the values for the KRs. Make sure they really are “shoot for the moon” goals. You should have only 50 percent confidence that you can make them. Challenge one another. Is someone sandbagging? Is someone playing it safe? Is someone foolhardy? Now is the time for debate, not halfway through the quarter.

Finally, take five minutes to discuss the final OKR set. Is the Objective aspirational and inspirational? Do the KRs make sense? Are they difficult? Can you live with this for a full quarter?

Tweak until they feel right. Then, go live them.

You’ll find a worksheet to help you out at http://eleganthack.com/an-okr-worksheet.

Improve Weekly Status Emails with OKRs

I remember the first time I had to write a status email. I had just been promoted to manager at Yahoo! back in 2000 and was running a small team. I was told to “write a status email covering what your team has done that week, due Friday.” Well, you can easily imagine how I felt. I had to prove my team was getting things done! Not only to justify our existence, but to prove we needed more people. Because, you know, more people, amiright?

So I did what everyone does: I listed every single thing my reports did, and made a truly unreadable report. Then, I began managing managers, and had them send me the same, which I collated into an even longer more horrible report. This I sent to my design manager, Irene Au, and my general manager, Jeff Weiner (who sensibly requested that I put a summary at the beginning).

And so it went, as I moved from job to job, writing long, tedious reports that, at best, were skimmed. At one job, I stopped authoring them. I had my managers send them to my project manager, who collated them, and then sent it to me for review. After checking for anything embarrassing, I forwarded it on to my boss. One week I forgot to read it, and didn’t hear anything about it. It was a waste of everybody’s time.

Then, in 2010, I got to Zynga. Now, say what you want about Zynga, but it was really good at some critical things that make an organization run well. One was the status report. All reports were sent to the entire management team, and I enjoyed reading them. Yes, you heard me right: I enjoyed reading them, even when were 20 of them. Why? Because they had important information laid out in a digestible format. I used them to understand what I needed to do and learn from what was going right. Please note that Zynga, in the early days, grew faster than any company I’ve seen. I suspect the efficiency of communication was a big part of that.

When I left Zynga, I started to consult. I adapted the status mail to suit the various companies I worked with, throwing in some tricks from Agile. Now I have a simple, solid format that works across any organization, big or small.

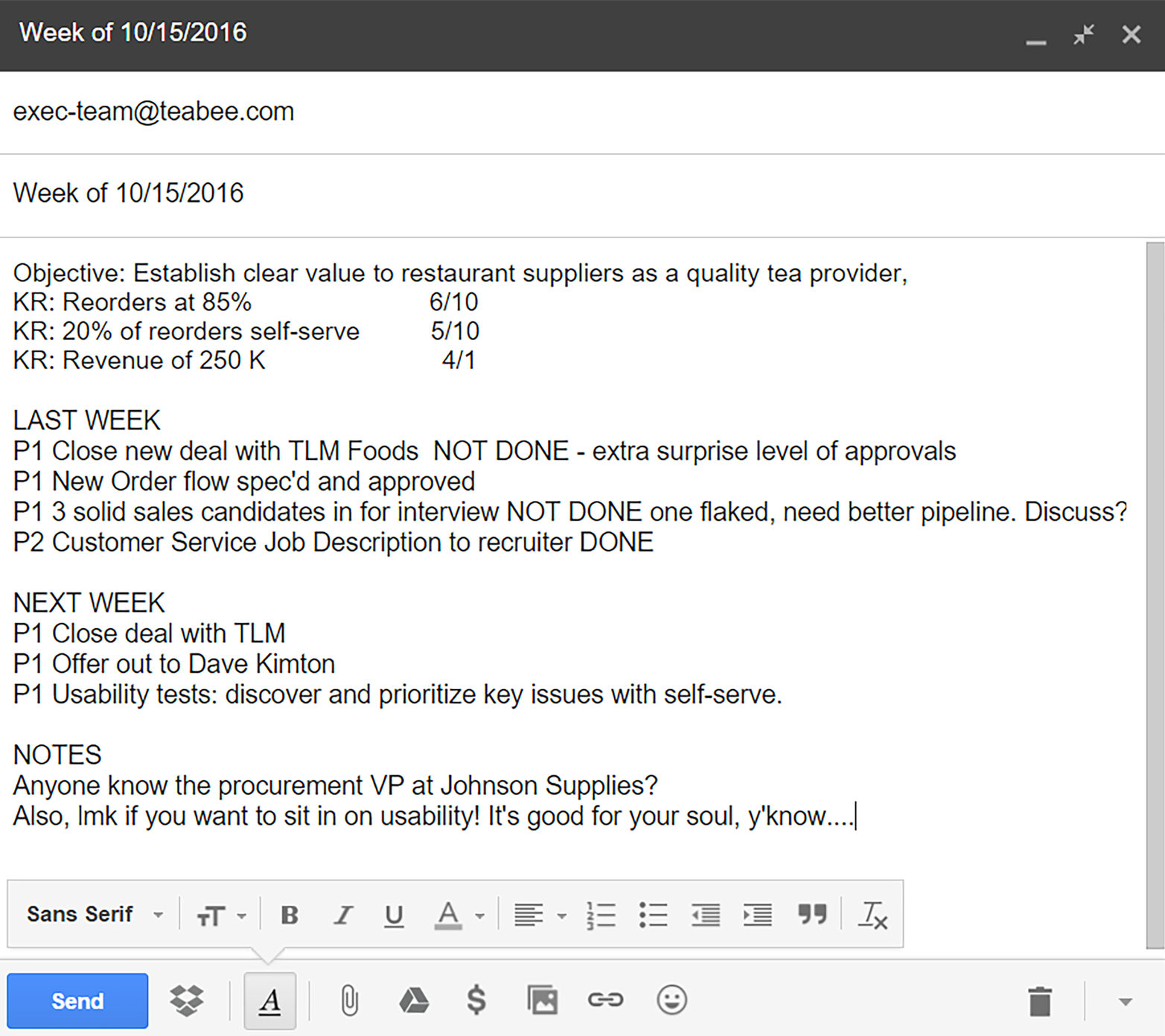

-

Lead with your team’s OKRs, and how much confidence you have that you are going to hit them this quarter.

You list OKRs to remind everyone (and sometimes yourself) why you are doing the things you do.

Your confidence is your guess of how likely you feel you will meet your Key Results, on a scale from 1 to 10. Mark your confidence red when it falls below 3, green as it passes 7. Color makes it scannable, making your boss and teammates happy. Listing confidence helps you and your teammates track progress and make corrections early if needed.

-

List last week’s prioritized tasks and whether they were achieved. If they were not, include a few words to explain why. The goal here is to learn what keeps the organization from accomplishing what it needs to accomplish. See Figure 4-1 for format.

-

Next, list next week’s priorities. List only three P1s (priority #1), and make them meaty accomplishments that encompass multiple steps. For example, “Finalize spec for project xeno” is a good P1. It probably encompasses writing, reviews with multiple groups and sign off. It also gives a heads up to other teams and your boss that you’ll be coming by.

“Talk to legal” is a bad P1. This priority takes about half hour, has no clear outcome, feels like a subtask and, not only that, you didn’t even tell us what you were talking about!

You can add a couple of P2s, but they should also be meaty, worthy of being next week’s P2s. You want fewer, bigger items.

-

List any risks or blockers. Just as in an Agile standup, note anything you could use help on that you can’t solve yourself. Do not play the blame game. Your manager does not want to play mom, listening to you and a fellow executive say “it’s his fault.”

As well, list anything you know of that could keep you from accomplishing what you set out to do—a business partner playing hard-to-schedule or a tricky bit of technology that might take longer than planned to sort out. Bosses do not like to be surprised. Don’t surprise them.

-

Notes. Finally, if you have anything that doesn’t fit in these categories, but that you absolutely want to include, add a note. “Hired that fantastic guy from Amazon that Jim sent over. Thanks, Jim!” is a decent note, as is, “Reminder: team out Friday for offsite to Giants game.” Make them short, timely and useful. Do not use notes for excuses, therapy or novel writing practice (see Figure 4-1).

This format also fixes another key challenge large organizations face: coordination. To write a status report the old way, I had to have team status in by Thursday night in order to collate, fact-check, and edit everything. But with this system, I know what my priorities are, and I use my reports’ statuses only as a way to ensure that their priorities are mine. I send out my report Friday, as I receive my reports. We stay committed to one another, honest and focused.

Work should not be a chore list, but a collective push forward toward shared goals. The status email reminds everyone of this fact and helps us avoid slipping into checkbox thinking.

Coordinating organizational efforts is critical to a company’s ability to compete and innovate. Giving up on the status email is a strategic error. It can be a task that wastes key resources, or it can be a way that teams connect and support one another.

Tracking and Evaluating OKRs

Two weeks before the end of each quarter, it’s time to grade your OKRs and plan for the next cycle. After all, you want to hit the ground running on day one of Q2, right?

There are two common systems for managing OKRs: confidence ratings and grading. Each has its benefits and downsides. We’ll begin with confidence ratings, the system I’ve outlined earlier. Confidence ratings are a simple system best used by startups and smaller teams, or teams at the beginning of OKR adoption. When you decide on your objective and three KRs, you set a difficult number you have a 50 percent confidence in achieving. This is typically noted by a 5/10 rating on the status-four square.

In your Monday commitment meeting, everyone reports on whether and how their confidence levels have changed. This is not a science, it’s an art. You do not want your folks wasting time trying to track down every bit of data to give a perfect answer; you just want to make sure efforts are directionally correct. During the first couple of weeks of OKRs, it’s pretty difficult to know whether you are making progress on achieving your Key results. But somewhere in week three or four, it becomes very clear whether you are getting closer or slipping. All of the team leaders (or team members, if a very small company) will begin to adjust the confidence rating as they begin to feel confident.

Then, the confidence rating will start to swing wildly up and down as progress or setbacks show up. Eventually, around two months, the confidence levels settle into the likely outcome. By two weeks from the end of the quarter you can usually call the OKRs. If they were truly tough goals—the kind you only have a 50/50 chance of making—there is no miracle that can occur in the last two weeks to change the results. The sooner you can call the results, the sooner you can make plans for the next quarter and begin your next cycle.

The advantage of this approach is two-fold. First, the team doesn’t forget about OKRs because they need to constantly update the confidence level. Because the confidence level is a gut check, it’s quick and painless, which is key for getting a young company in the habit of tracking success. The second advantage is that this approach prompts key conversations. If confidence drops, other leads can question why it is happening and brainstorm ways to correct the drop. OKRs are set and shared by the team; any team member’s struggle is a danger to the entire company. A leader should feel comfortable bringing a loss of confidence to the leadership team and know that he’ll have help.

At two weeks before the end of the quarter you mark your confidence as 10 or 0. Success is making two of the three key results. This style of grading leads to doubling down on the possible goals and abandoning efforts on goals that are clearly out of range. The benefit of this is to stop people spinning their wheels on the impossible and focus on what can be done. However, the downside is some people will sandbag by setting one impossible goal, one difficult goal, and one easy goal. It’s the job of the manager to keep an eye out for this.

The second approach to OKRs ratings is the grading approach. Google is the most famous for using the grading approach. At the end of the quarter, the team and individual grade their results with data collected. 0.0 means the result was a failure, and 1.0 means the result was a complete success. Most results should land in the 0.6 to 0.7 range. From the Google official site on using OKRs, ReWork:

The sweet spot for OKRs is somewhere in the 60–70 percent range. Scoring lower may mean the organization is not achieving enough of what it could be. Scoring higher may mean the aspirational goals are not being set high enough. With Google’s 0.0–1.0 scale, the expectation is to get an average of 0.6 to 0.7 across all OKRs. For organizations that are new to OKRs, this tolerance for “failure” to hit the uncomfortable goals is itself uncomfortable.

Ben Lamorte is a coach who helps large organizations get started and sustain their OKR projects. He regularly uses a grading approach rather than confidence approach. From his article, “A Brief History of Scoring Objectives and Key Results”:

As an OKRs coach, I find most organizations that implement a scoring system either score the Key Results at the end of the quarter only or at several intervals during the quarter. However, they generally do not define scoring criteria as part of the definition of the Key Result. If you want to use a standardized scoring system, the scoring criteria for each Key Result MUST be defined as part of the creation of the Key Result. In these cases, I would argue that a Key Result is not finalized until the team agrees on the scoring criteria. The conversation about what makes a “.3” or a “.7” is also not very interesting unless we translate the “.3” and the “.7” into English.

I’ve arrived on the following guidelines that my clients are finding very useful (see Figure 4-2).

Here’s an example showing the power of defining scoring criteria upfront for a Key Result.

Key Result: Launch new product ABC with 10 active users by end of Q3.

-

Grade 0.3 = Prototype tested by three internal users

-

Grade 0.7 = Prototype tested and approved with launch date in Q4

-

Grade 1.0 = Product launched with 10 active users

This forces a conversation about what is aspirational versus realistic. The engineering team might come back and say that even the 0.3 score is going to be difficult. Having these conversations before finalizing the Key Result ensures that everyone’s on the same page from the start.

As well as precision, Google sets high value on transparency. All OKRs, individual and team, are posted on the intranet, and team progress is shared throughout. Again, from ReWork:

Publicly grade organizational OKRs. At Google, organizational OKRs are typically shared and graded annually and quarterly. At the start of the year, there is a company-wide meeting where the grades for the prior OKRs are shared and the new OKRs are shared both for the year and for the upcoming quarter. Then the company meets quarterly to review grades and set new OKRs. At these company meetings, the owner for each OKR (usually the leader from the relevant team) explains the grade and any adjustments for the upcoming quarter.

And ReWork: warns against the danger of set and forget:

Check in throughout the quarter. Prior to assigning a final grade, it can be helpful to have a mid-quarter check-in for all levels of OKRs to give both individuals and teams a sense of where they are. An end of quarter check-in can be used to prepare ahead of the final grading.

This is also done differently across teams. Some do a midpoint check, like a midterm grade; others check in monthly. Google has always embraced the approach of “hire smart people, give them a goal, and then leave them alone to accomplish it.” As it’s grown, OKRs are implemented unevenly, but OKRs continue to allow that philosophy to live on.

Ben Lamorte also shares a simple technique to keep OKR progress visible: progress posters. Several of his clients have set up posters in the hallway that are updated regularly with progress. Not only does this make OKRs more transparent and visible across teams, it can be effective for communicating scores on Key Results and really creating more accountability. It just doesn’t look good if your team hasn’t updated any scores when you’re already a month into the quarter. Most of these posters include placeholders to update scores at four to eight planned check-ins throughout the quarter. Certainly OKR posters are not for all organizations, but they can be quite effective in some cases.

No matter whether you use confidence check-ins or formal grading (or a combination of both), there is one last piece of advice from ReWork: that is important to keep in mind:

OKRs are not synonymous with performance evaluation. This means OKRs are not a comprehensive means to evaluate an individual (or an organization). Rather, they can be used as a summary of what an individual has worked on in the last period of time and can show contributions and impact to the larger organizational OKRs.

Use the accomplishments of each person to determine bonuses and raises. If you use the status report system described in this report, it should be easy for individuals to review their work and write up a short summary of their accomplishments. This report can guide your performance review conversations. Some things shouldn’t be automated, and the most important part of being a manager is having real conversations about what an employee has contributed—and what he hasn’t.

If you rely on OKR results to guide your decisions, you will encourage sandbagging and punish your biggest dreamers. Reward what people do, not how good they are at working the system.

A Short Note on OKR Software

When you set a resolution, what is the first thing you do? Want to lose weight? Buy an expensive treadmill. Want to start running? Buy fancy shoes. Plan to diet? Buy the best scale on the market. Or maybe you just buy 15 diet books. Sadly, adopting OKRs is treated the same way. People buy software, and hope it’ll do the hard work of setting and managing your goals.

There are a ton of tools for OKRs out there, and many are quite good. But buying a tool is the last step you want to take, not the first. The right way to adopt OKRs is to adopt them in a lightweight fashion, then experiment with different approaches until you find the system that gets you results.

Begin with these tools first:

-

A whiteboard, to write ideas of what your objectives will be

-

Post-it notes, to brainstorm good KRs

-

PowerPoint/Keynote, to track confidence and efforts against the objectives

-

Email, to send out statuses

-

Excel, if you decide you want to do formal grading (Google offers a tool for grading on its Rework website

The first quarter that you feel you have truly mastered OKRs, go shopping.

Getting Started with OKRs

Just like new technologies, methodologies can suffer from the hype cycle. OKRs are no exception; I’ve met a number of people deeply disillusioned with OKRs and unwilling to give them a second chance. But just like Lean or Agile, simply because a given company implements the approach badly does not mean the approach has no value.

When a company first hears about the Objective and Key Result approach, they are excited.

“Now I know what the secret of success is!” and they rush to implement it across the entire company. Often a manager thinks this is the silver bullet she’s been seeking. This feeling is well documented by Gartner—it’s called a Hype Curve (see Figure 5-1).

But the first time you try OKRs, you are likely to fail. Although OKRs are not complicated, they are difficult work and often require cultural change. Failure can be a dangerous situation, as your team can become disillusioned with the approach and be unwilling to try them again. You don’t want to lose a powerful tool just because it takes a little time to master.

There are three approaches you can use to reduce this risk:

- Start with only one OKR for the company

-

By setting a simple goal for the company, your team sees the executive team holding itself to a high standard. It won’t be surprising when next quarter it is asked to the do the same. And by not cascading it, you both simplify implementation and see who chooses to adopt OKRs and who will need coaching.

- Have one team adopt OKRs before the entire company does

-

Choose an independent team that has all the skills to achieve its goals. You can then trumpet its success if it happens, or wait a cycle or two until it perfects its approach and then roll out OKRs across the company.

- Start out by applying OKRs to projects to train people on the objective-result approach

-

The company GatherContent is a great example. Every time it has a major project, it first asks what the objective is for this project and how we will know if we’ve succeeded. (This case study is included in my new book, Radical Focus (Boxes & Arrows, 2016).

In all these approaches, avoid the deadly OKR mistakes and focus on learning what works in your company culture. By starting small and tracking how OKRs will work in your organization, you increase the chances of your company adopting a results-based approach, and reduce the danger of a disillusioned team.

OKRs are not a silver bullet. They should be part of a suite of approaches a company adopts. They exist to create focus while increasing employee satisfaction and productivity. Combined with Lean, Agile, and a strong management approach, OKRs will help get you out of the trough of disillusionment to the plateau of productivity.

Quick Tips for Using OKRs

-

Set only one OKR for the company, unless you have multiple business lines. It’s about focus.

-

Give yourself three months for an OKR to have an effect. How bold is it if you can do it in a week?

-

Keep the metrics out of the Objective. The Objective is inspirational.

-

In the weekly check-in, open with the company OKR, and then do groups. Don’t do every individual; that’s better in private one-on-ones, which you do have every week, right?

-

OKRs cascade; set company OKRs, and then groups/roles, and then individuals.

-

OKRs are not the only thing you do; they are the one thing you must do. Trust people to keep the ship running, and don’t jam every task into your OKRs.

-

The Monday OKR check in is a conversation. Be sure to discuss change in confidence, health metrics, and priorities.

-

Encourage employees to suggest company OKRs. OKRs are great bottom up, not just top down.

-

Make OKRs available publicly. Google has them on their intranet.

-

Friday celebrations are an antidote to Monday’s grim business. Keep it upbeat!