How to recruit for user research

Tools and techniques for recruiting UX research participants.

Photo montage (source: Pixabay)

Photo montage (source: Pixabay)

My name is Harvey Milk, and I’m here to recruit you.

Harvey Milk

It’s hard to conduct user research if you don’t have anyone to research. Recruitment lets you find people that have the information you seek to learn. Recruitment is risky since the effort hinges on getting the right people in the room. There are a number of factors at play, and various methods a team can use to find the right kind of participants. Before worrying about the risks and before scheduling participants, you first must document whom you want to recruit.

Participant Identification

One of the first activities your team will do when planning recruitment is identify participants to recruit. It’s helpful that most projects have existing information on customers, giving your team a jump-start on identifying whom you want to recruit and, more importantly, why you want certain types of people to be involved in the research. Common sets of data to identify participants include:

-

Past qualitative research

-

Current analytic reports

-

Customer segments

-

User profiles

Past Qualitative Research

If there is preexisting research on your product, refer to the existing materials. Your approach should be one of validation. Ask what is missing from the participant criteria. If a different team conducted the research, ask them how the participants mapped to their needs and what they might do differently in a new round of recruiting.

Current Analytic Reports

There is a wealth of knowledge about users hidden in the analytics mentioned in Chapter 3. Depending on the details, you can quickly learn where users are geographically, or what personal demographics are important. Analytics can expose gaps in your target demographics and identify opportunities to reach out to underrepresented user groups.

Customer Segments

One source of information that’s easily overlooked is customer segments organized by marketing teams. Good customer segments are based on purchased data sets or those collected internally and should not be discounted.

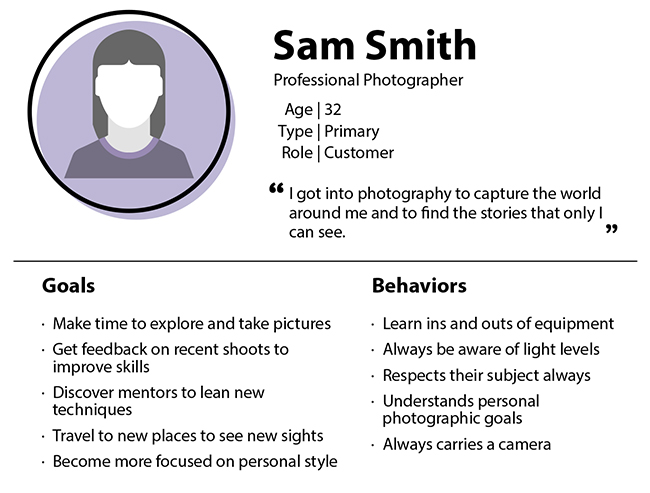

User Profiles

If your team doesn’t have personas from quantitative and qualitative data, you will need to write baseline user profiles to guide recruitment (see Figure 1-1). A user profile is handy for a variety of situations, not just for recruitment. By taking time to document user profiles, you can generate future personas with more ease. User profiles can be shown to stakeholders for review, ensuring recruits align with a stakeholder’s presumptions. If there is disagreement, you can resolve this prior to recruiting.

This can be an educational moment for stakeholders who may not be familiar with product research. Because our focus is on behaviors less than demographics, user profiles can complement and validate existing marketing research, as you will be approaching the same subject matter, just from a different point of view.

Breaking down profiles

After collecting information about the type of people you’d like to include, you need to break that information down by referring to your research goals and the goals of the product as a whole. You may end up with an overwhelming number of profiles and you can’t recruit for all of them. Before creating your recruitment screener, a short survey to find people, your team will need to prioritize profiles so everyone knows the importance of different audiences.

There are a number of ways to measure priority. One method is to look for those users the team feels are most likely to interact with the product on a regular basis. Another way to evaluate priority is to focus on reaching users that do not yet use the product. Refer back to the underlying goals to guide the prioritization, and you should have the profiles you want to recruit against.

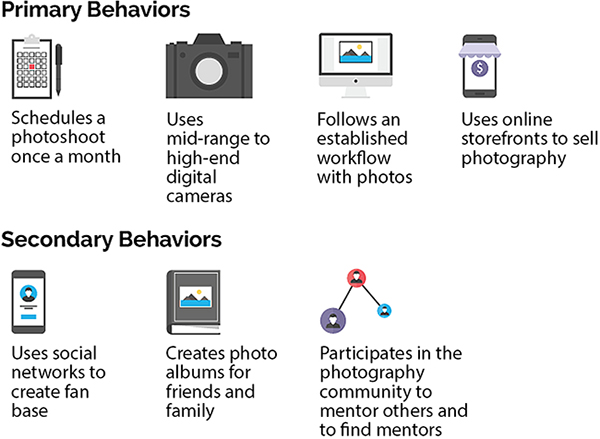

Identifying key behaviors

User profiles aren’t all about demographics and potential lifestyle decisions. One key component of a good user profile is listing existing or potential behaviors (see Figure 1-2). To get this list of behaviors, refer to the goals your product seeks to help users accomplish, as mentioned in Chapter 2. Now, think through the actions and behaviors someone would go through to accomplish those goals given today’s world and the different forms of technology they use.

Some common examples include:

-

Does the person prefer to shop using a mobile app or desktop website?

-

Does the person compare product reviews when making a new purchase? Do they seek information online or in store?

-

Where is the person using the product? At home, their office, or in transit?

You’ll screen against these actions and behaviors when recruiting users. Your team can prioritize this list of behaviors based on frequency, impact, risk, and any other factors that might influence someone’s resulting experience from using a product to accomplish their goals.

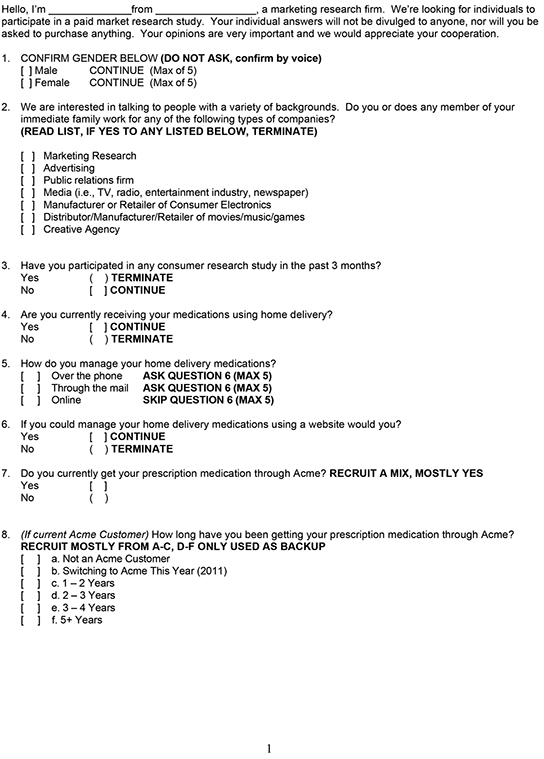

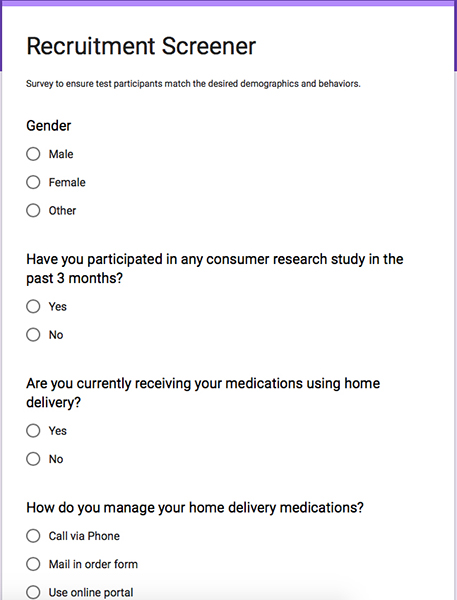

Recruitment Screener

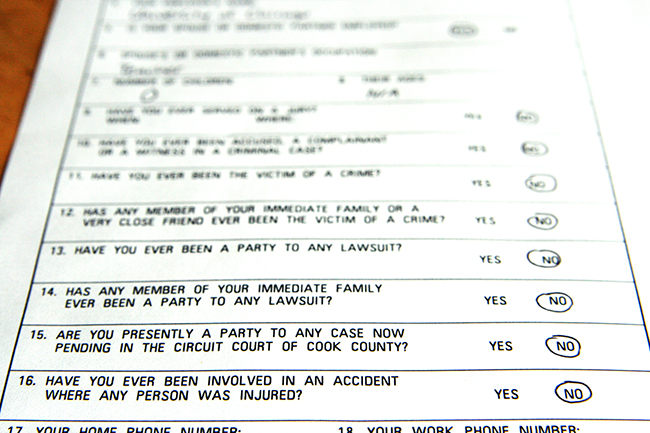

Recruitment screeners (see Figure 1-3) are internal documents defining what user profiles you plan to research. They provide a consistent basis for your team or external vendors to recruit against and ensure more cohesive data sets.

While it can be tempting to skip screening and conduct research with a friend, family member, or someone off the street, such an approach will expose you to risks and gaps in your findings. For instance, if you’re researching an online Medicare application form and evaluating college students, the quality of data isn’t going to help the team. College students don’t have the context, life experience, or understanding of the subject matter to help.

Screening is universal across all research methods. The better you screen, the better your data will be. And quantitative research supports screening too. Passive triggers—such as purchasing a product, using an ISP’s location, or visiting a minimum number of pages on a site—may be set off before a survey is presented.

What Screeners Look Like

Recruitment screeners are often surveys consisting of multiple-choice questions. While the number of questions varies, a screener should take no longer than 10–15 minutes to complete. With screeners, shorter is always better, regardless of method (in person, over the phone, or online).

Multiple-choice questions allow a binary decision to be made: certain responses disqualify a participant, while others confirm their desirability. Standard usability screeners (Figure 1-4) are very similar to the screener presented in a summons for jury duty (Figure 1-5).

Basic Demographics

Key demographics—such as age, lifestyle, education, and income levels—play an important role in recruiting, since some products may appeal only to a certain user group. Demographics allow you to quickly narrow down the pool of potential participants to those that are more likely to exhibit the behaviors you can learn from.

Behavioral Demographics

While basic demographics establish a baseline for recruitment, behavioral demographics establish the filter to ensure participants have the information and experience needed to inform the product’s design. One example of a behavioral demographic is someone’s online shopping habits. Are they more likely to look in store and buy online? When do they decide to buy online versus in a store?

Or to use a more complicated example: Does this person attempt to resolve issues online first when they have a question? At what point do they feel the need to contact a help line for assistance from a human?

Quotas

Time waits for nobody. And with deadlines determining how much time can be spent on research, teams define quotas of how many participants to research from various user profiles (see Figure 1-6). Quotas are also helpful to have after you’ve defined whom you want to speak to. The potential audience of brain surgeons is significantly smaller than people looking for a new car, and understanding the available participant pool is helpful to avoid overreaching.

Assuming participant availability is not an issue, qualitative research generally targets three to five users per user group. These numbers shift based on how important it is to hear from a specific user profile and how difficult it might be to find people that align with one of your profiles. Remote, unmoderated tests and quantitative research methods may see as many as hundreds or even thousands of participants.

These quotas can be sprinkled throughout a screener survey. As the recruiter works through the screener, some questions with more than two potential responses can have numbers associated with those responses. These numbers ensure you meet with people that matter and your participant pool isn’t skewed.

These numbers will tell the recruiter that you want to recruit, say, five people that are heavy online shoppers, and three people that are moderate online shoppers.

Recruitment Methods

The best method of recruitment identifies quality participants. There are a number of common techniques to generate a participant pool. Some methods take significant time and effort, while others can be implemented quickly.

Internal Versus Public Recruiting

It’s important to address the differences between recruiting participants for an internal product compared to a product for the general public. Internal recruiting seems easier than public recruiting, since you have a relatively captive audience: colleagues within the organization.

One factor impacting internal recruitment is the support of management. If you face the common challenge of management blocking access to employees, rather than get frustrated, involve managers at all levels early in planning. Having a voice in the process encourages managers to contribute both their time and their direct reports’ time. This is paramount when you are recruiting time-sensitive or ultra-specialized participants in organizations where even an hour-long session may seem detrimental to a manager.

When recruiting from the general public you lose direct access to participants, but there are a variety of recruiting methods available to streamline the task, which we outline next.

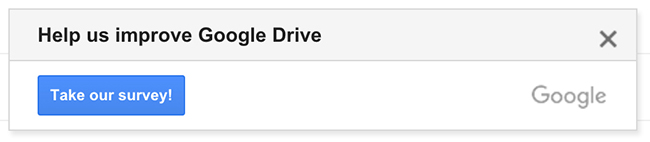

Self-Recruiting

One of the most common methods of recruitment is to do it yourself. The DIY method can be slow and draining, and you should plan for extra lead time since your team won’t be dedicated to recruitment fulltime. Plan for a minimum of two weeks for DIY recruiting, and you may start with a call for participants from colleagues, friends, and family. Still, you should include a screener email or survey to ensure appropriateness. Because of the limited formality, tools like Google Forms can be paired with an introduction email to screen possible recruits (see Figure 1-7).

Cold calling

Cold calling is probably the most uncomfortable recruiting method. This requires access to a list of phone numbers of individuals who have opted in to provide feedback. Numbers may be obtained through an online survey or, in some cases, purchased from companies that specialize in selling customer contact information.

Even when customers agree to being contacted, there can be a moment of confusion as to why you are calling them. To handle this, your opening script should clearly state the reason why you’re calling and how you got their number.

In-person intercepts

One recruiting option is to go to where the participants are located (see Figure 1-8). If recruiting participants in situ, you want to go to a high-traffic area where you are likely to have access to people fitting your user profiles. It is important to have a 5- to 10-second elevator pitch of who you are and what you are doing. We highly encourage you to carry a clipboard, as this lends you more credibility when you approach people or when they ask who you are. Don’t get discouraged if most people don’t seem interested. People live busy lives and in many cases have trained themselves to ignore strangers approaching them to complete some sort of survey.

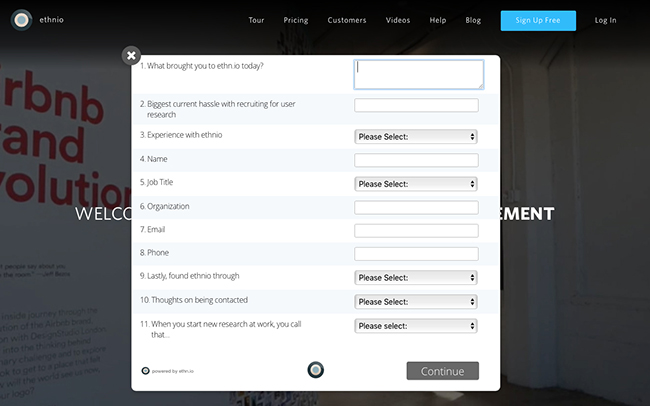

Online intercepts. People accessing your product online or through a companion website are candidates for participating in user research. For passive analytics, users participate simply by using the site. For more active surveys or unmoderated tests, users may be presented with a pop up asking if they are interested in participating in research activities. This call to action should quickly explain what the activity is and what kind of incentive is available to participants. One of the common tools for doing this type of recruitment is Ethnio, an online screening service (Figure 1-9).

Other alternatives. Other ways to recruit include banner ads targeted to visitors to a product’s website, or email blasts to users who’ve agreed to learn about updates. Banner ads are often paid advertisements. Email blasts, on the other hand, obtain a list of potential recruits from marketing departments. These are not great as a primary recruiting approach, but your team can’t be recruiting 24/7. By having these passive methods available, you might get a few users that your normal methods might miss.

Outsourcing Recruiting

Recruiting doesn’t have to be your team’s responsibility. Companies specialize in finding participants on your behalf. In some ways, this is a more effective method. It’s important that someone from your team manages and oversees the recruitment efforts, however. This is especially true for client-based recruiting, as detailed next.

Third-party recruiting

Market research firms have perfected the method of finding people that fit into demographically based buckets. These firms take well-written recruitment screeners and call people in their databases for a reasonable fee. While this fee depends on the complexity of your screener, the resulting participants tend to be better than most DIY methods.

Client-based recruiting

For client-based work, it’s possible to offload recruiting to members of the client team. This is a good method if recruitment efforts depend on relationships, such as a wealth management tool. Using this method increases the importance of having a team member oversee the recruitment efforts. It’s easy for clients to find the most available participant, regardless of appropriateness. This may lead to more junior or less experienced participants, which can bias results.

Scheduling

The art of scheduling research participants takes time and patience. Your team will balance the needs of the moderators, observers, and participants. For intensive qualitative research methods, you should aim to schedule only three to four participants a day. For lighter forms of qualitative methods, this increases to five to six participants in a day without exhausting the research team.

Quantitative methods have fewer scheduling constraints, as participants either are unaware of the session through web analytics or access the research tool for a short period of time. For unmoderated research a participant should be able to complete the session in 15–30 minutes. After 30 minutes without a moderator to keep them on task, participants lose focus.

Backups

It is rare that everyone who agrees to participate in a qualitative research activity is able to contribute meaningful information. This is expected, and many teams schedule backup participants in case the scheduled ones don’t attend. This is a good practice, no matter the form of research.

No shows

If you have 10 people scheduled for a series of research sessions, you’ll be lucky if 8 show up. This doesn’t speak to the value of the work your team is doing or the level of interest in your product. Lives and schedules are complicated, and spending an hour with some stranger can easily be deprioritized.

When this happens, backup participants are key to having research data. It’s not uncommon to schedule a backup participant across multiple research sessions. The backup waits to be called on if another participant doesn’t show up. This way, if the second or third participant doesn’t show, the backup may be used. Backups are compensated for their time in similar ways as participants. If you don’t have backups, take this time to catch up on work that has built up. If clients are uncomfortable with no shows, explain that this is an unavoidable part of the process.

Duds

No recruitment effort is bulletproof. You will get participants who make you wonder how they made it through the screener. As with no shows, this is part of the process and happens during most research activities. While “duds” may not be perfect participants, they still have something to contribute. You will need to modify your tactics during the session to hyperfocus on key goals, and you’ll need to flag any notes from that session as supplemental to your data set. Chapter 10 explores improvisation techniques as a tool for adjusting your approach on the fly in more detail.

Recruitment Challenges

Every recruitment effort has challenges. Some of the most common hurdles aren’t challenges, but excuses we tell ourselves to avoid recruiting in the first place. The following scenarios have stopped more research opportunities than any stakeholder claiming insufficient funding.

I Don’t Have Users…Yet

Just because the product you are creating isn’t on the market today doesn’t mean you don’t have “users.” Your product is trying to solve a problem. Your product has potential competitors and, barring that, analog counterparts. Identify how people work around the existing problem by applying solutions passed down through generations, hacking together fixes, or using another product in an unintended way for a desired outcome. The things people do and how they do them are out there somewhere. Your focus of research should be not the product itself, but the problem your product will solve.

Small Target Audience

Some products serve a very niche group of people. This is common for internal products that are used by a well-defined pool of users. Just because a user pool is small, however, doesn’t mean it should be a challenge to reach. In fact, it’s the opposite. Small user groups are a focused audience. It might take some relationship managing with supervisors or other gatekeepers, but it will pay off in the end. For example, if you need to talk with high-level vice presidents who are in charge of procurement at an organization, your time might be better spent reaching out to their assistants to schedule a meeting rather than contacting the vice presidents directly.

Common Lies We Tell Ourselves

Without a cohesive screener, product teams often find recruiting challenging. Two of the most common indicators of a loose or undefined screener are “everyone is a user” and “everything is a secret.”

Everyone is a user

Simply put, everyone is not your user. Even Facebook, which is available to everyone, started with a specific user group: college students. If you are designing for a very large population of people, user groups can subdivide the pool into manageable segments that relate to how, when, and why people might use your product.

Everything is a secret

No team wants word of their product to get out before they are ready to send out a media kit. There are ways to ensure news of your product doesn’t go public until you’re ready. As mentioned in Chapter 6, your nondisclosure agreements legally silence participants. You can also display prototypes or early releases without naming your company, product, or team.

In reality, the people you recruit are not the type to perform corporate espionage. In fact, they will be honored to be included, and once your product goes live they could be some of your strongest supporters.

Exercise: Priming Your Screener

There is a quick exercise you can conduct with your team to prime your recruitment screener. Together, you will map out what key demographics you want to target and the types of behaviors that you want to observe.

-

List out basic demographics.

List out the basic demographics like age, education, income, family, ethnicity, and employment. Members of the team, on their own, select the demographics they think matter for your product and then share with the group. Based on what the team shares, find the top three to five demographics and write those down for all to see.

-

Write down desired behaviors.

Next, have each person on the team write down the actions or behaviors they would like to learn more about that people do with your product. Once they’ve listed out their behaviors, have them share them with the group and note any overlaps. Discuss any behaviors that are mentioned once to understand why that person thought it was important to research more about it. Likewise, discussing overlaps uncovers clear gaps in existing knowledge. Once more, pick the top three to five behaviors that the team agrees are the most important to learn more about.

-

Write screening surveys.

Once the basic demographics and behavioral demographics are identified, have team members suggest questions and answers to address the behaviors identified in Step 2 that can be used to screen potential participants. The resulting survey will be your draft screener, which you can review and iterate after finishing the group exercise.

Parting Thoughts

Recruitment can be one of the biggest risks you will face. You don’t want to get to the end of your research and find out that you didn’t collect any information that actually helps your team. This isn’t meant to scare you; rather, we want you to understand that recruitment isn’t an area you want to skim over when starting research.

We have both been part of research efforts where recruitment was shortchanged. Those experiences have given us the tools we’ve presented in this chapter so you can avoid the same problems. Remember, at the heart of any good research effort is the collection and communication of information. If you don’t use the right sources for that information, then the value of your research is limited.