HiveBio: Access Granted

Community labs are the forefront of the DIYbio movement.

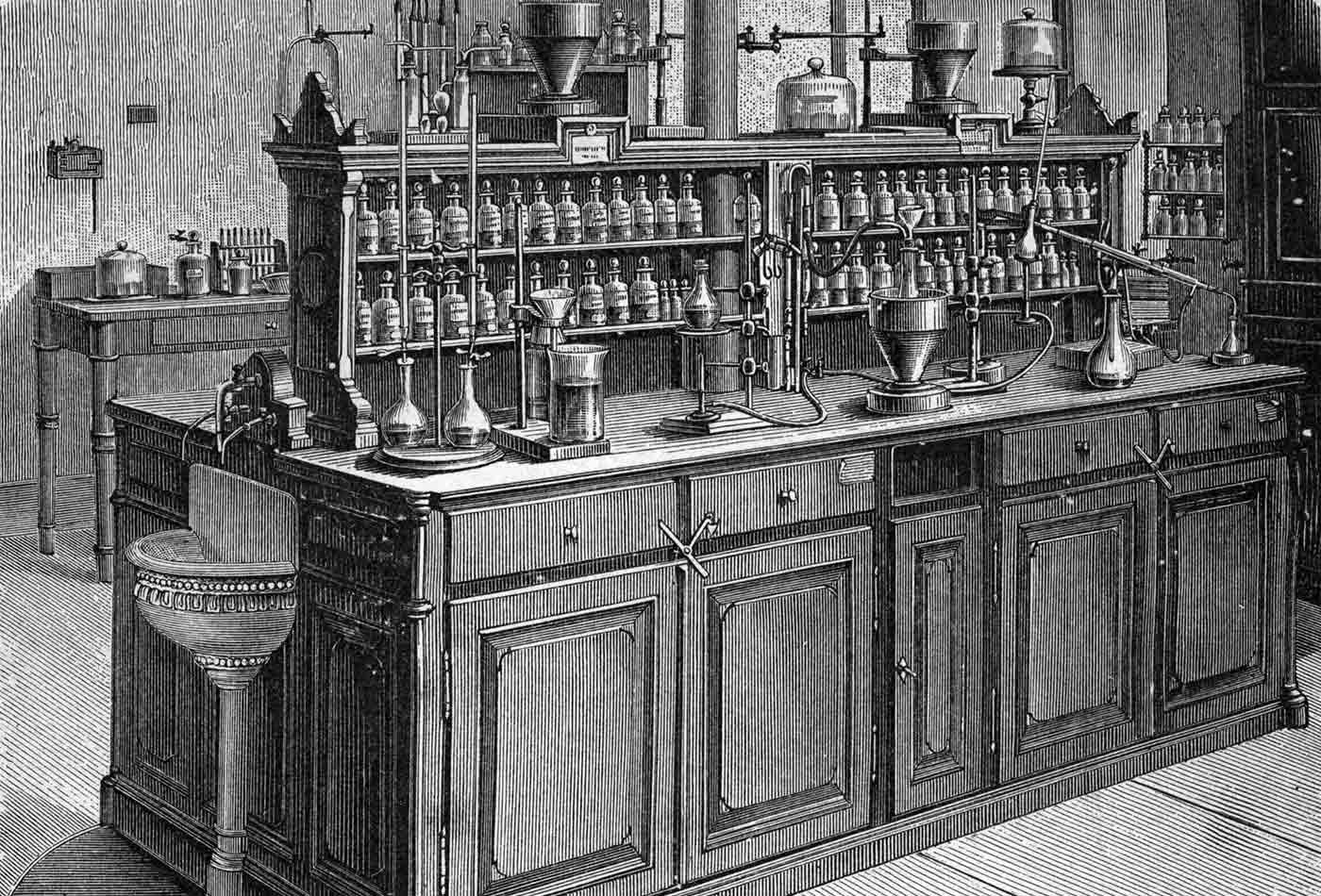

Chemical laboratory at the University of Leipzig, 1894. (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Chemical laboratory at the University of Leipzig, 1894. (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Bergen McMurray has cherry-red hair and shoulders painted with black ink tattoos. You probably wouldn’t be surprised to learn that she’s worked as an artist, a photographer, and a graphic designer. But McMurray has a few more titles that set her apart. She’s a loving mother, she’s published in Nature, and in her spare time, she happens to lead a buzzing colony of do-it-yourself biologists.

Do-it-yourself biology, or DIYbio, is part of a growing movement which seeks to give people the tools to learn without formal education. “Punk,” “maker,” or “hacker”—the DIY community can go by many names, all of which embody the same directive: democratize science. DIYbio empowers the individual to seek scientific knowledge through trial and error, getting hands dirty in books and bench work alike. In the same way computer tinkering and garage electronics powered the human element of the digital revolution, DIYbio provides the average individual a pathway to biological literacy.

McMurray’s philosophy aligns to the ethic of the DIY community. “I believe that everyone, regardless of education level or income or age, should [have] access to the resources needed to learn and build and create,” she said.

But for biology, finding this access can be hard to come by. Expensive and potentially hazardous chemicals, specialized equipment, particular safety and environmental contamination protocols: all of these can present insurmountable hurdles. Even the most basic equipment—a simple pipette, for example—can cost hundreds of dollars, while autoclaves or necessary chemicals are locked behind laboratory doors accessible only to academics or industry types.

In Seattle, and other cities, the answer comes in the form of a DIYbio community lab.

Community Labs: A Public Space for Science

Tucked away in a quiet corner of the city, HiveBio bustles with activity on any given Saturday as curious Seattleites of all ages and backgrounds gather for the chance to experience biology hands on. In the laboratory, two tables take up most of the room, while on the walls shelves hold donated equipment, latex gloves, and Rubbermaid containers filled with multicolor, plastic, microcentrifuge tubes. Around these tables, DIY enthusiasts and curious minds gather as McMurray guides a tour of the human brain (Figure 1-1).

HiveBio is one of a growing rank of spaces known as community labs. These institutions are the forefront of the DIYbio movement, offering a place to learn fundamentals of biology, a network to meet fellow DIYbio enthusiasts, and an infrastructure to develop and execute your own biology project. You might think of the them like community rec centers, but instead of swimming in a pool or taking your child to a day camp, you’re exercising your brain with projects and educating your kids with classes. “Community labs are the hub where citizen scientists can find each other, learn new skills, and come together to create something greater than the sum of its parts,” McMurray said.

In 2013, this was just the kind of place McMurray was looking for. When her son was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder, she sought to learn everything she could about the human brain. But without a formal degree in science, she hit a road block.

“[N]o lab would grant me access,” she said. “It was possible to to rent lab space, but the cost was extremely high.”

What’s a maker at heart to do but build her own solution to the problem?

McMurray set about gathering her dream team. Kathriona Guthrie-Honea, an impassioned and motivated high-school student seeking space for a class project, became cofounder. Dr. Michal Galdziki, a veteran of the DIYbio scene, was to be chief science officer. And the role chief operations officer was championed by Elizabeth Scallon, founder of a green lab movement focused on recycling unused laboratory equipment. By the fall of 2013, HiveBio Community Laboratory was open for the public.

A Model of Engagement

HiveBio acts as a DIYbio hub for the Pacific Northwest’s maker community, providing a lab space, offering classes, and maintaining active projects. Like any community hub, HiveBio has grown to serve the community’s needs. Whereas a community lab in Brooklyn might cater to local artists, or a space in Silicon Valley might offer advice for new start-up companies, HiveBio retains a uniquely Seattle feel.

Take Citizen Salmon, the current flagship project of HiveBio. In a region where salmon is king, tracking the origin of store-bought fish connects consumers to the local fishing economy.

While learning lab basics like PCR amplification, coupled with bioinformatic techniques, citizen scientists use genetic markers unique to regional spawns to approximate the geographic origin of their food. Similarly, in a tech-wise city, additional projects at HiveBio focus on open source instrument development on a DIY budget: QPCR and liquid handling instruments top the marquee.

The bread and butter of HiveBio, however, are the 18 unique classes regularly offered on weekends. On the list: squid dissections, building a smartphone microscope, modeling protein folding, the organic chemistry of smell, and, of course, a hands-on tour of the brain. The courses are taught by volunteers, mostly professors at nearby universities, local industry experts, or members of the DIYbio community, and they have proven hugely popular. In the 2013–2014 fiscal year, HiveBio saw over 100 people enroll in its classes.

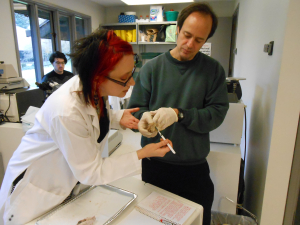

Of the citizen scientists active in HiveBio, many have little to no formal training in biology, and many, like the ones pictured in Figure 1-2, were young students.

“Educationally, my background is more in the business side,” said Zach Mueller, a local tech employee and longtime DIYbio enthusiast. “It’s definitely been a very diverse set of people. There’s a lot of people like me that don’t have the bio background and are interested in [DIYbio] out of curiosity.”

HiveBio is also making strides to engage the community beyond its doors. Monthly community discussion groups enfold new members of the DIYbio community, while dedicated volunteers liaise with local educators to bring hands-on STEM education to K12 students.

The Future Is DIY

Community labs are gaining traction. According to diybio.org, the online organization of global DIYbiologists, at least 34 bio-themed maker spaces exist in the United States, with dozens more across the globe. As an additional measure of making it in the DIYbio world, community labs even have their own track in the global iGEM competition.

The success of community labs is driven in part by the coordination and efforts of those who’ve found the secret to making a functioning organization. For its part, HiveBio has initiated an annual conference, SWARM, designed for maker space coordinators in the Pacific Northwest. In 2015, the first annual SWARM brought together 30 organizers from Portland to Vancouver to discuss ways to boost community participation and interest in DIY spaces.

What makes a community lab sustainable? McMurray said that, as with most things, finances are the limiting reagent for HiveBio.

“As with any grassroots organization, money is the largest factor holding us back.”

HiveBio, which operates as a 501c3 nonprofit organization, receives most of its revenue from class fees, grant money, and membership dues, a standard trope for community labs across the US. Equipment comes mostly from donations, and the organization is fueled entirely by volunteer dedication.

For a future when money is no object, HiveBio hopes to expand current operations to touch more lives, aiming to develop a scholarship department to take active learning of biosciences to more at risk communities.

As for Mueller—he envisions his own DIYbio future as an entrepreneur.

“I do have an interest, long, long term, to maybe start a company in the field of biotech. [HiveBio] is just helping me build up my skill set now to understand what the bounds of possibility would be.”

Maybe the future will see “business incubator” added to HiveBio’s resume, but for now, McMurray said HiveBio will keep toward its goal of bringing DIYbio access to all.

“[DIYbio’s] most important role is showing the world that anyone, regardless of age, socioeconomic status, or education level can perform scientific research and be contributing members of the greater scientific community,” she said. “Most of us grow up with idea that science is exclusive to genius. Community labs are breaking down these barriers and teaching people of all ages that science is for everyone.”

You can learn more about HiveBio by visiting the website hivebio.org and following @HiveBio on Twitter and HiveBio Community Labs on Facebook.