Hardware by the numbers: Startups

Learn the most pertinent data behind the latest IoT trends.

(source: O'Reilly)

(source: O'Reilly)

Hardware by the Numbers

Last year, we started our Hardware by the Numbers trend report by looking at the origin story of hardware startups. We charted the rise of the Maker Movement as a foundational shift, and examined how the awareness it brought to the possibilities of “hacking the physical world” had inspired thousands to come together and form hardware communities across the world. These communities resided in an ever-increasing number of hackerspaces, and became ecosystems that spawned “Maker Pros.” Many of these Maker Pros went on to start hardware companies, moving from projects to full-fledged products that were to be sold to a mainstream audience.

In January 2014, The Economist declared a “Cambrian moment” for startups, stating that there were approximately 140,000 globally. While there is no canonical “taxonomy” of the increasingly large startup ecosystem, at the topmost level it is reasonable to split into “Hardware” and “Software.” Many hardware startups are fond of saying that they’re really software companies, or that the hardware is merely a tool for gathering data, but the skill set and capital requirements required to successfully bring a physical product to market set these companies apart from those that are purely focused on building software, regardless of the business model that they select.

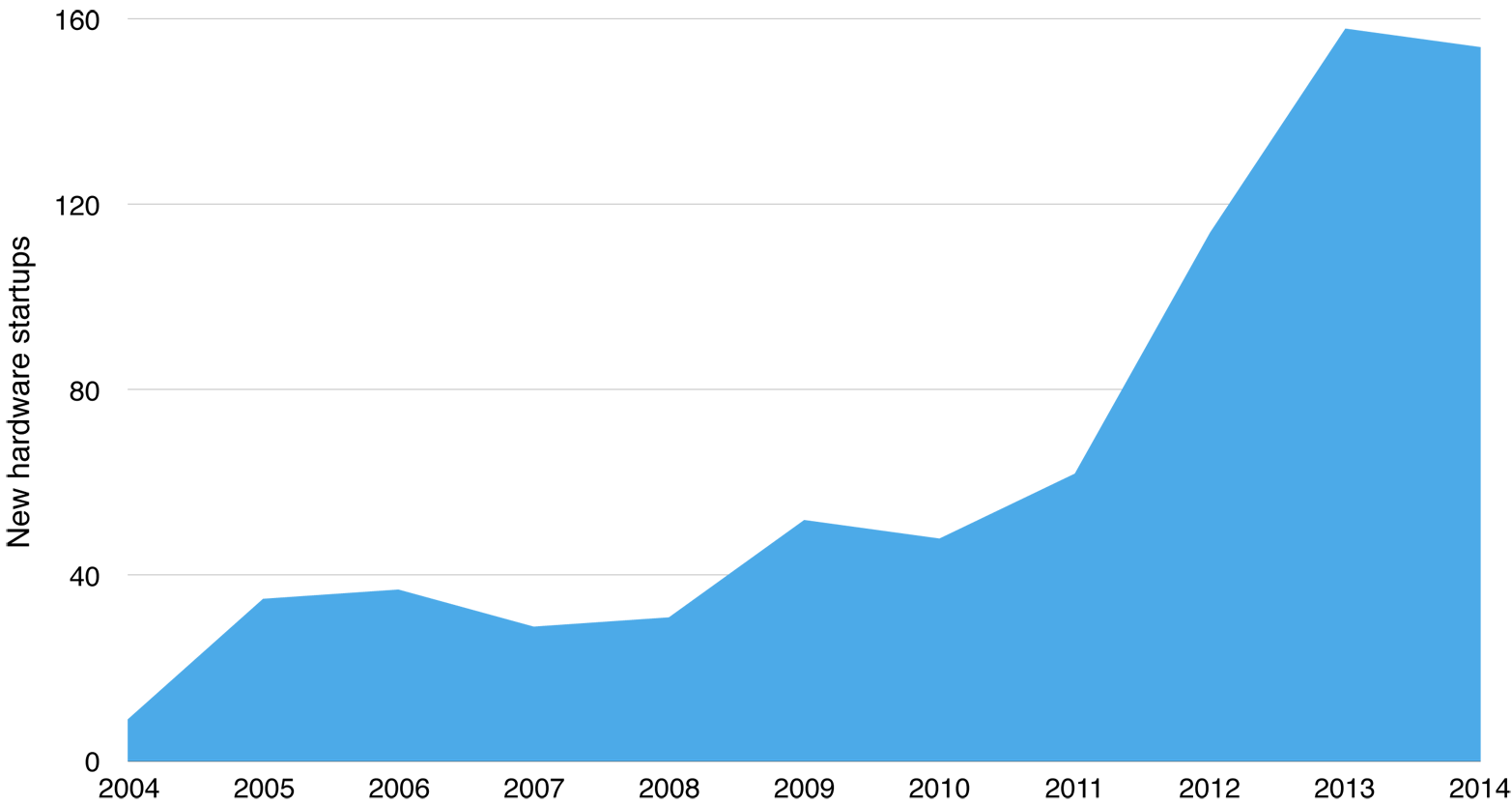

There is no authoritative source for the number of hardware startups launched in any given year, but estimates using AngelList data seem to indicate that the number increased sharply in 2012 and 2013, and leveled off a bit in 2014. It’s difficult to track unfunded companies, so our graph below uses the proxy of first money raised to assign a birth year to the company.

For many companies, the first money in comes alongside participation in an accelerator program. Again, identifying a comprehensive list is challenging, but as of May 2015 there are at least ten prominent accelerators around the world, focused solely on hardware.

Perhaps one of the most interesting recent developments in the hardware accelerator ecosystem was the entrance of popular “predominantly software” accelerators such as TechStars and Y-Combinator into the hardware space. In the second half of 2013, TechStars partnered with digital powerhouse R/GA. Y-Combinator, perhaps the most prestigious accelerator, had dabbled with the occasional hardware company in past classes for quite some time—Pebble, a smartwatch company from the Winter 2011 class, is one notable example. In February 2015, YC heralded a more official focus on the sector by announcing a partnership with hardware seed investor Bo.lt (which was originally founded as a hardware accelerator) and CAD software powerhouse Autodesk, which now provides participant startups with access to prototyping facilities at its Pier 9 location.

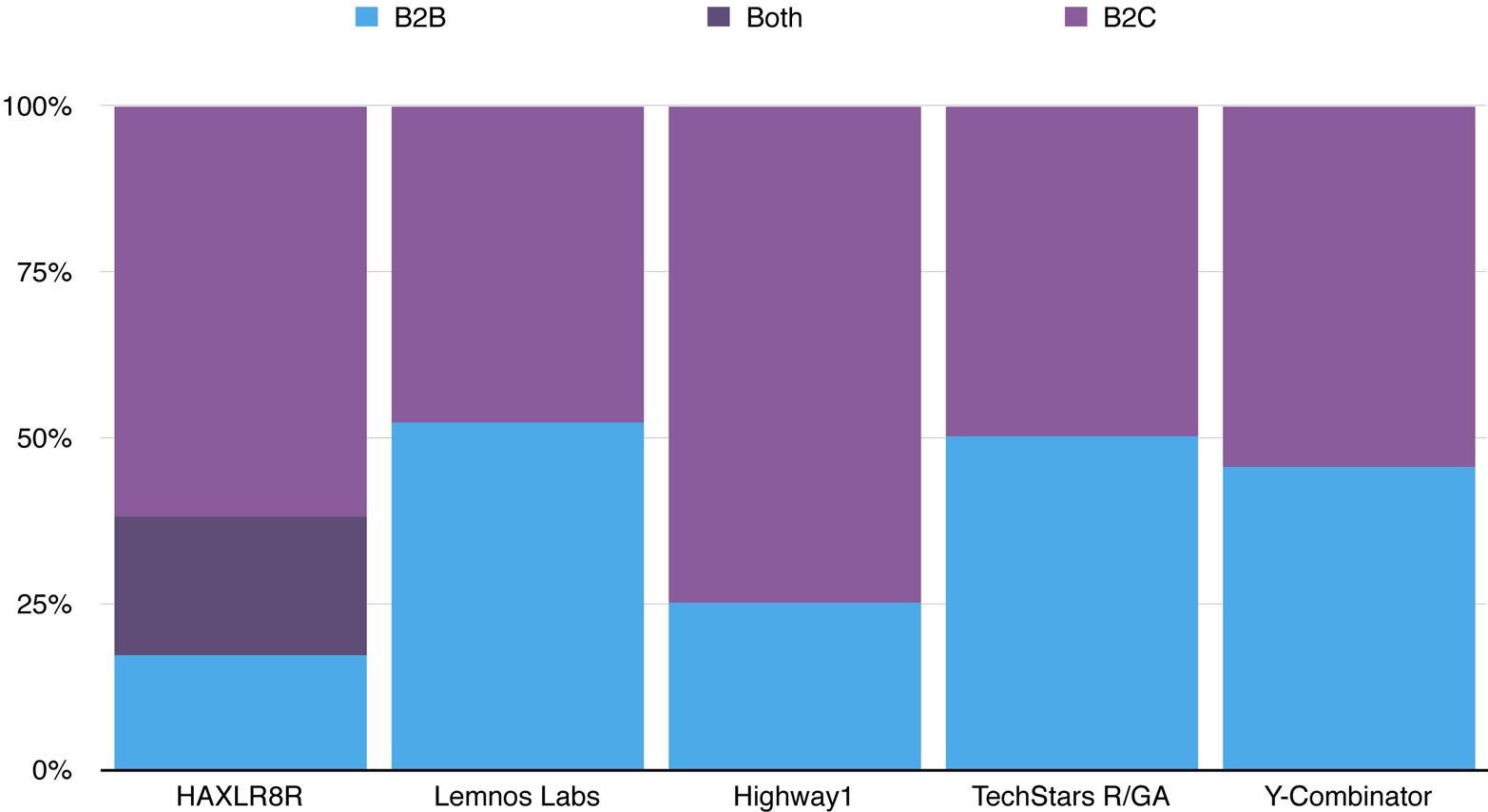

Hardware Startups Evenly Split between B2B and B2C Business Models

When looking at the companies participating in the hardware startup ecosystem, one trend of note is that we are now at a relatively even split between B2B and B2C business models for hardware startups participating in accelerators.

- HAXLR8R: reports that of the 65 companies it has worked with since it began in 2012, 17% overall have been exclusively B2B focused, with another 21% targeting customers in both B2B and B2C. Of the 12 companies it accelerated in 2014, 3 (25%) were B2B.

- Lemnos: since its inception in 2012, Lemnos has invested in and accelerated 21 companies, of which 10 (52.4%) were B2B. In 2014, 50% of its class was B2B.

- Highway1: one of the newest accelerators in this list, Highway1 has had 4 classes in total since Fall 2013. A total of 46 companies have completed the program. In 2014, there were 25 companies, of which 6 (25%) were B2B.

- TechStars: in its official hardware startup accelerator in partnership with R/GA, 30% of class one was B2B, and 60% of class two was B2B.

- Y-Combinator: before the official focus, YC had 153 companies in 2014, of which 9 (5.9%) were hardware. So far, in 2015 there have been 114 companies total, of which 11 (9.6%) were hardware companies; 45.5% of those hardware companies were B2B.

The data set is very small. Currently, the majority of hardware companies are still B2C, but B2B percentage has increased. One explanation for the initial prevalence of B2C companies may be the influence that crowdfunding has had on taking a product to market. Many hardware companies publicly “launch” via crowdfunding—it’s effectively a presale campaign.

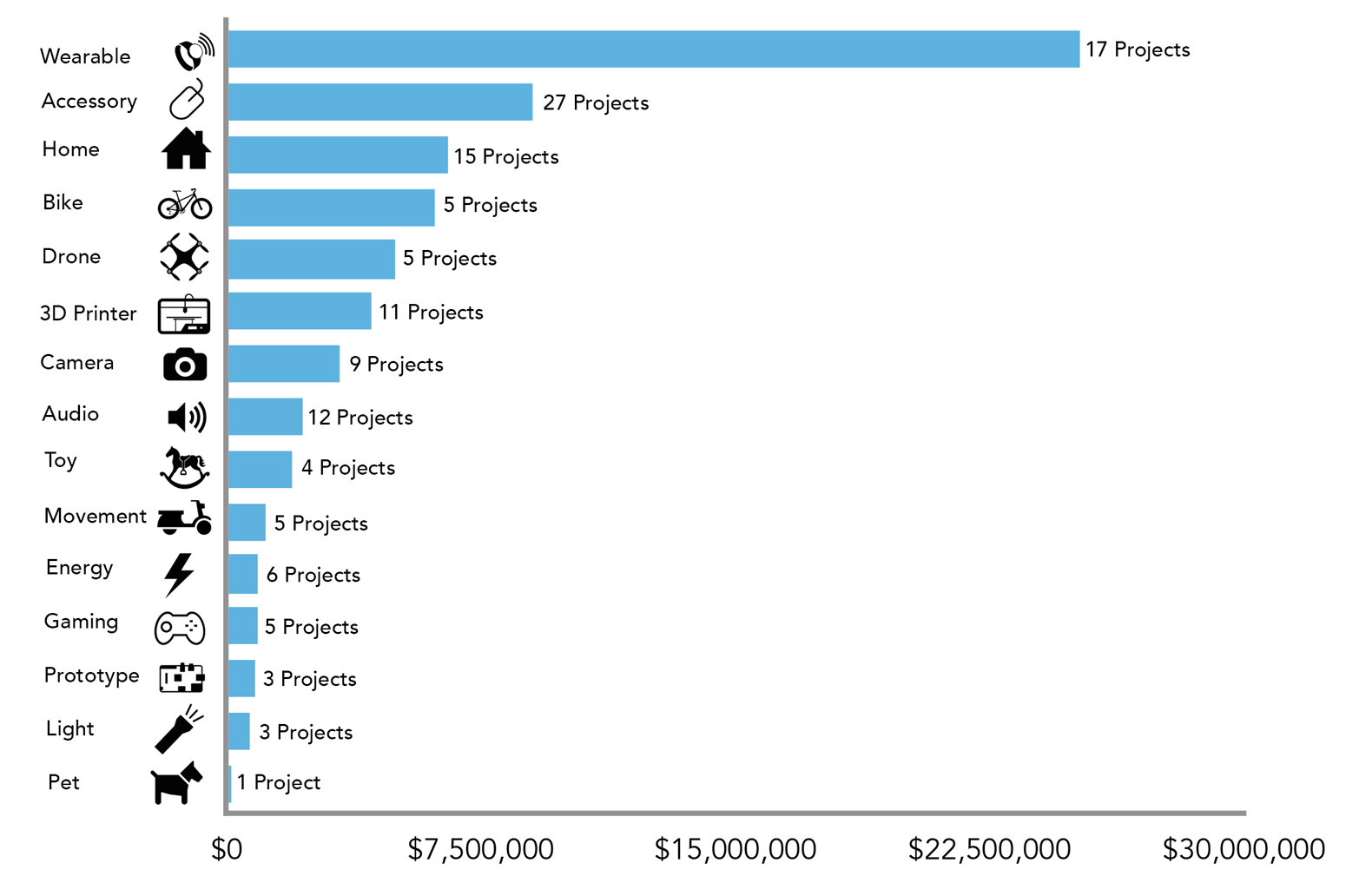

Since the vast majority of backers are regular consumers who tend to see crowdfunding as a combination of sponsorship and pre-ordering, it would follow that B2C hardware projects would be more successful on these sites than B2B startups. Matt Witheiler of Flybridge Capital studies this market closely. He recently analyzed the types of projects that were most successful on crowdfunding sites in Q1 of 2015. The companies, which were selected from both Kickstarter and Indiegogo, had all raised over $100,000.

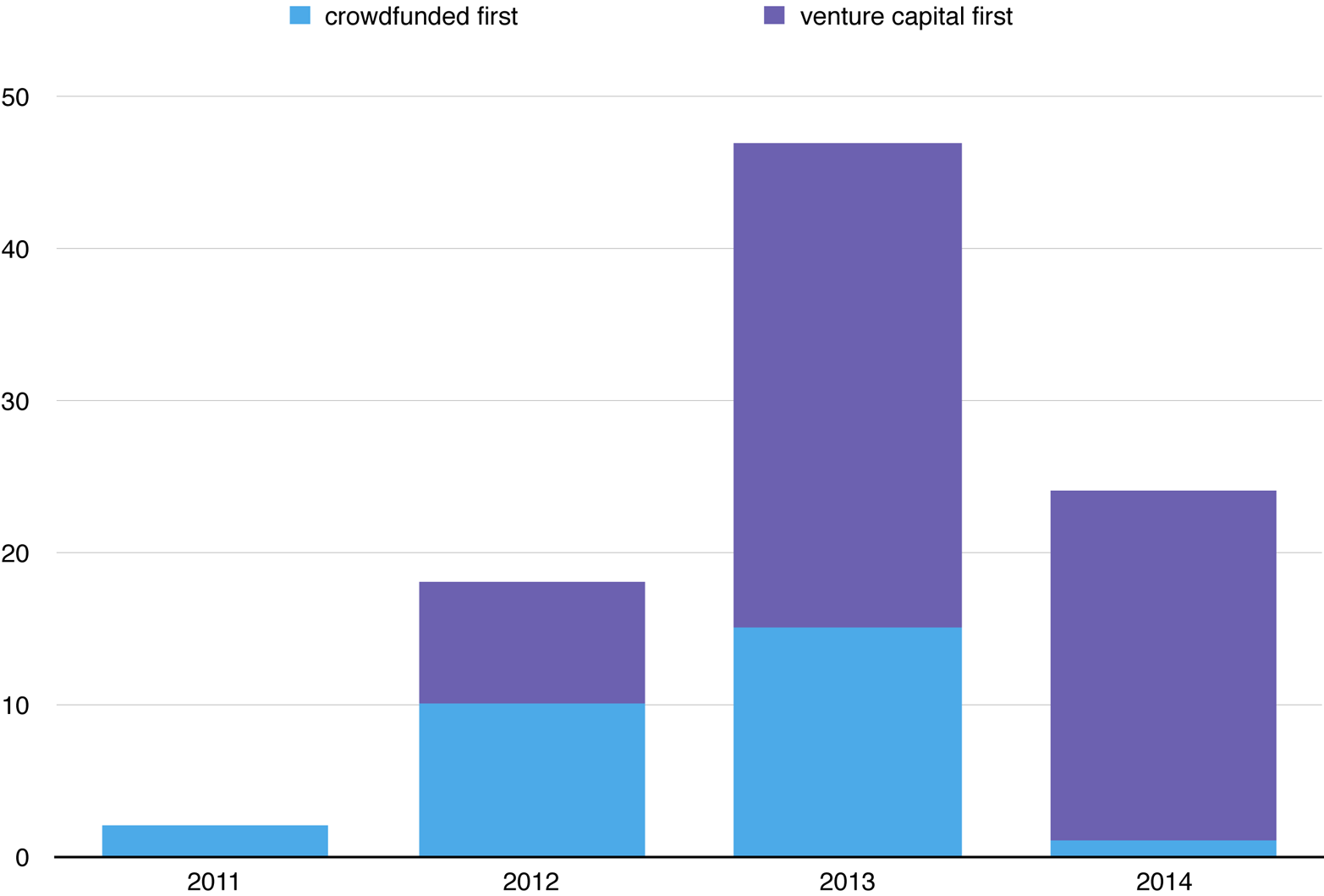

The conventional wisdom that crowdfunding success predicts or drives future venture success no longer seems to be true. Prior to 2013, a crowdfunding raise typically happened before raising a venture round—many venture-backed hardware startups were “discovered” when their crowdfunding raises attracted press and contributions. It is now increasingly common to do a crowdfunding raise at the culmination of an accelerator, or after raising an angel or seed round. Using Matt Witheiler’s data set of companies that raised both $100,000 on a crowdfunding site and took venture funding, we see that an increasing percentage of companies pursue a campaign after the venture raise:

We used Mattermark’s startup data platform to look at early-stage “Hardware” and “Internet of Things” companies (we defined “early” to mean startups that had raised some capital, but pre-Series B). There were 486 companies that met these criteria. 189 were specifically classified as B2B IoT; 199 were classified as B2C IoT, though there was some overlap. The non-IoT B2B hardware included medical device platforms, semiconductors, and battery tech companies. Of the IoT B2B companies, many produced beacons or RFID technologies, often geared toward specific industries (e.g., indoor tracking systems for retailers). A fairly large number of companies were software layers for IoT security. Several produced functional-prototyping products offering “connectivity as a service.”

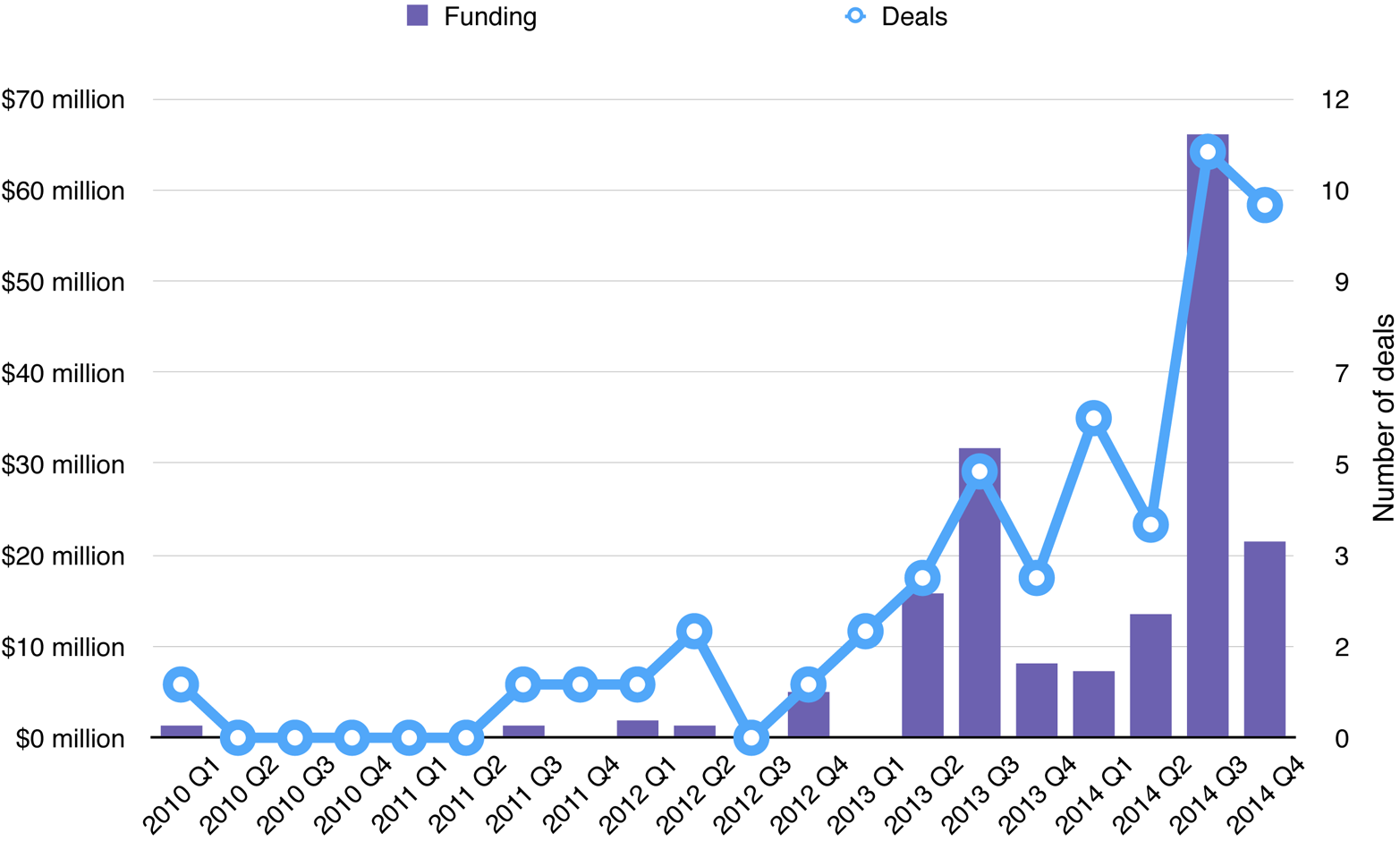

Dow Jones VentureSource states that the total amount of venture capital invested in electronics and computer hardware companies overall hit $2.56 billion in 2014, which exceeded the previous high of $2.24B in 2000. Drones continue to be extremely hot. While they are technically a subset of robotics companies, they are now treated separately on most popular “Bloomberg for Startups” ecosystem-tracking platforms.

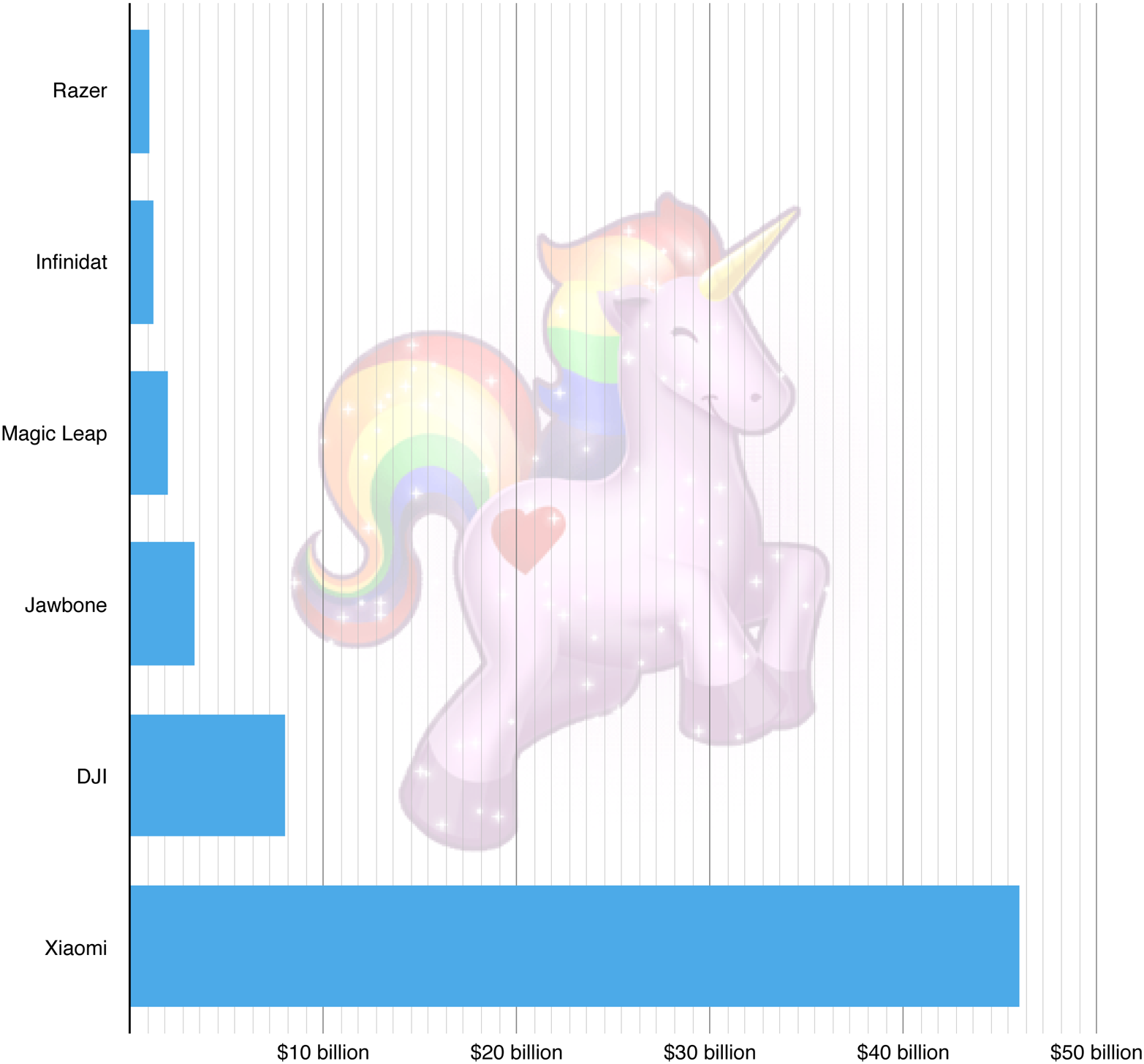

The startup community has a new term for describing companies valued at over $1 billion: unicorns. The past year has seen several new hardware entrants into the Unicorn Club: Jawbone ($3.3B), Magic Leap ($2B), Infinidat ($1.2B), and Razer ($1B). Two more—smartphone maker Xiaomi ($46B) and drone company DJI ($8B)—are based in China.

And, of course, there are the acquisitions. There were several unicorn-caliber acquisitions in the hardware sector in 2014: Google bought connected-home startup Nest for $3.2B. Facebook picked up Oculus VR for $2B. Apple acquired Beats for $3B. And there were two IPOs: camera company GoPro (which currently has a market cap of $8B), and Mobileye (market cap $7.6B), which builds anti-collision hardware and software for self-driving cars.

Outside of the $1B+ market, there were several other high-profile acquisitions. While 2014 did not compare to the 2013 robotics acquisition blitz by Google, they did purchase Skybox, a satellite company, and Dropcam, a connected-home company. Intel bought Basis, the smartwatch maker, for around $100M. 3D Robotics, itself a startup, purchased Sifteo, a connected-toy company. Samsung bought connected home “connective tissue” startup SmartThings.

Emerging Trends among Five of the Largest Industries in the U.S.

Let’s examine the sectors that connected hardware is transforming at a big-picture level. We’ve selected five of the largest industries in the United States to look at the latest applications. The general trend is as follows: increasingly inexpensive sensors lead to greater ease of instrumentation, a substantial amount of data is gathered by these devices, and mining that data for insights leads to the creation of more efficient, cost-effective, or profitable business strategies.

Health

An individual’s progression through a healthcare experience can take several forms. There is maintaining wellness, treating an ailment, and (particularly for an aging population) potentially managed long-term care. Hospitals and providers who are confronted with rising costs are interested in leveraging data to reduce overhead costs and improve outcomes. The majority of connected devices related to healthcare have taken the form of wearables, particularly in the wellness and long-term care phases. In 2014, Apple and IBM announced a collaboration on a data-driven health platform to link iPhone and Apple Watch user data to IBM’s Watson analytics platform, with the intent of deriving insights through the resulting data set. At an enterprise level, diagnostic devices such as MRIs and treatment devices such as radiation oncology machines are increasingly connected. Companies such as Varian Medical Systems, Elekta, and Ventana Medical Systems are shipping connected devices that alert technicians to when machines are in need of repair or other servicing (e.g., if the helium levels in the MRI scanner are low) and are capable of remote software updates—they call this “over the shoulder assistance.” Monitoring hospital and pharmaceutical supplies is also increasingly connected—a rising number of hospitals are using RFID technology to implement track-and-trace and automated restocking in an effort to cut down on waste and reduce costs. Some also use it to monitor caregiver-patient interactions, which can be used to trace the spread of infection in case of infectious disease exposure. However, estimates place the number of hospitals currently using these systems at ~10%; this is still the early days of industry adoption. MarketResearch.com’s “Big Data in the Internet of Things (IoT): Key Trends, Opportunities, and Market Forecasts 2015 – 2020” predicts a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15.1% in IoT deployments in the healthcare sector—“the highest segment for growth during the forecast period.”

Energy

In the energy sector, the promise of the “smart grid” continues to drive IoT adoption. Ericsson reports that “the global number of devices being managed by utility companies is projected to grow from 485 million in 2013 to 1.53 billion in 2020. The utilities industry is the second largest source of M2M service provider revenue, behind only the automotive and transport industries.” Adoption of remote monitoring of energy usage and demand is not new; the industry has been at the forefront of M2M adoption for quite some time. The current goal is to shift from what Ericsson describes as simple M2M, primarily focused on simple efficiency maximization and load-demand management, to leveraging the IoT’s open information and cloud processing power. The goal is to increase the intelligence of grids, to enable the creation of platforms that can facilitate the development of applications and services, and to design systems capable of evolving. GE speaks of “self-healing grids.” In the oil and gas industry, sensor data is increasingly being used to monitor the safety of the operations themselves.

Financial Services/Insurance

One might not think of the financial services industry as being particularly well-suited to transformation through connected devices. This industry doesn’t directly interact with physical goods or assets in quite the same way as the others in this list. However, the financial services sector is thinking about IoT. Deloitte suggests that the industry may adopt smarter and more secure ATMs, or use connected device data to offer financial products tied to those devices (e.g., a car’s computer indicates that it’s broken down, customer could receive an offer for a new auto loan). However, the immediate potential for IoT in financial services is in insurance. Inexpensive sensor devices and ubiquitous data can transform the industry from one that relies on actuarial tables, to one that leverages behavioral and usage data to model and price risk at an extremely granular level. State Farm has partnered with ADT and Lowe’s IRIS, and Allstate works with Rogers Smart Home Monitoring—both leverage connected home systems to monitor potential problems and offer customers price breaks in exchange for using these devices. Progressive launched its automobile insurance product “Snapshot” in 2011; upstart insurer MetroMile offers a similar product, tying insurance to per-mile vehicle usage and driving behavior. However, adoption rates have been low overall—in March 2014, Progressive reported that 2 million vehicles have participated in the program, and there are approximately 233 million cars and light-duty vehicles registered in the United States. The primary barrier to adoption appears to be consumer concern about insurance companies “spying” on them.

Agriculture

Industrial agriculture has long leveraged technology to improve yields and reduce costs. The “Internet of Cows” was mentioned several times at Solid last year, accompanied by slides of photogenic bovines wearing ear tags that communicate to a machine whether and how long to milk them. Agriculture continues to be at the forefront of IoT innovation, particularly in terms of conservation of resources and maximization of yield. Precision agriculture is a $2 billion market in the U.S. right now, and IBISWorld expects that to grow at 4.5% annually through 2017. Monsanto, for example, is building on its October 2013 acquisition of data and insurance company Climate Corp, leveraging data to produce software that can be loaded onto tractors and other planting tools to help optimize the physical planting of the fields. Increasingly inexpensive drones and satellites are providing access to new types of data about crops and soil. Even pest control is transforming; Semios manufactures a device that hangs from a tree in an orchard. It can identify pests, disseminate pheromones with an awareness of wind direction, automatically count the insects that it traps, and can correlate trap counts with weather conditions and microclimates to forecast problems before they occur. GE, John Deere, Syngenta, and other large agricultural firms are prioritizing connected devices—both as a way to improve their bottom line and as a tool for ensuring that farmers are able to continue to feed the world.

Logistics and Transportation

This industry is responsible for moving goods around the world, and it’s another sector that Gartner predicts will be fundamentally transformed by the Internet of Things. The logistics sector has many moving parts—literally. Trucks take products from the factory to the dock or airport. Ships and planes transport goods across oceans. In intermodal transit, shipping containers are moved from a ship directly onto a truck or rail chassis, and sent on their way. Eventually, there is a “last-mile” delivery, either to a retail shelf or to a customer’s home or business. Currently, GPS is used to help supply chain managers identify where their shipment is, and companies such as UPS have complex routing optimization tools that take real-time traffic data into account. Weather data, traffic conditions, temperature inside the container (critical for perishables), and tilt of pallets as they are moved (particularly critical for some pharmaceutical shipments) are all knowable—FedEx, for example, has offered a platform called SenseAware since 2009. For logistics professionals, the vision is to move beyond passive gathering and monitoring of data to true bidirectional communication says Gartner. It’s worth mentioning that startups have made significant inroads into logistics this year. An increasing number of companies has appeared in the space.

Outside of the private sector, we’re seeing governments pick up the pace as well. IoT adoption by governments is moving us down the path to instrumented cities. Public-private partnerships, many involving startups, aim to improve efficiency in parking, water and energy usage, waste services management, and more. Even elevators in city highrises are becoming instrumented; the goal is a responsive system that predicts breakdowns before they occur.

Regulatory Trends in IoT: Watching, Waiting

As both private and public sector adoption of connected devices increases, regulators are still assessing the degree to which they should get involved. In January 2015, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) published a report called “”Internet of Things: Privacy and Security in a Connected World”, which made recommendations on how to strike an appropriate balance between technological innovation and protection of consumer privacy and security. These included:

- Incorporating security considerations into the design from the start, and testing them prior to product launch.

- Recommending “defense-in-depth” multi-layered security strategies for systems with “significant risk.”

- Monitoring devices across the full extent of their life cycle, with an eye toward patching any vulnerabilities that become apparent over time

- Alerting consumers about the possibility that their data will be gathered, and providing an option to opt out.

- Suggesting “data minimization”—limiting the collection of data, or the duration of time the data is stored—because storing customer data for a long period of time could make a company an increasingly likely target for hackers, or might increase the chances that the data would be used in a way that the customer did not expect.

Then in March of 2015, the FTC announced the Office of Technology Research and Investigation (OTRI), which was formed with the goal of providing “expert research, investigative techniques and further insights to the agency on technology issues involving all facets of the FTC’s consumer protection mission, including privacy, data security, connected cars, smart homes, algorithmic transparency, emerging payment methods, big data, and the Internet of Things.”

The U.S. government has taken no firm steps toward IoT regulation; the FTC report suggests that such regulation would be premature given how rapidly IoT technology is changing. However, the House Energy and Commerce subcommittee held hearings in March to discuss the economic benefits and job opportunities that continued expansion of IoT technologies offers, as well as the potential privacy and security risks.

Synthetic Biology

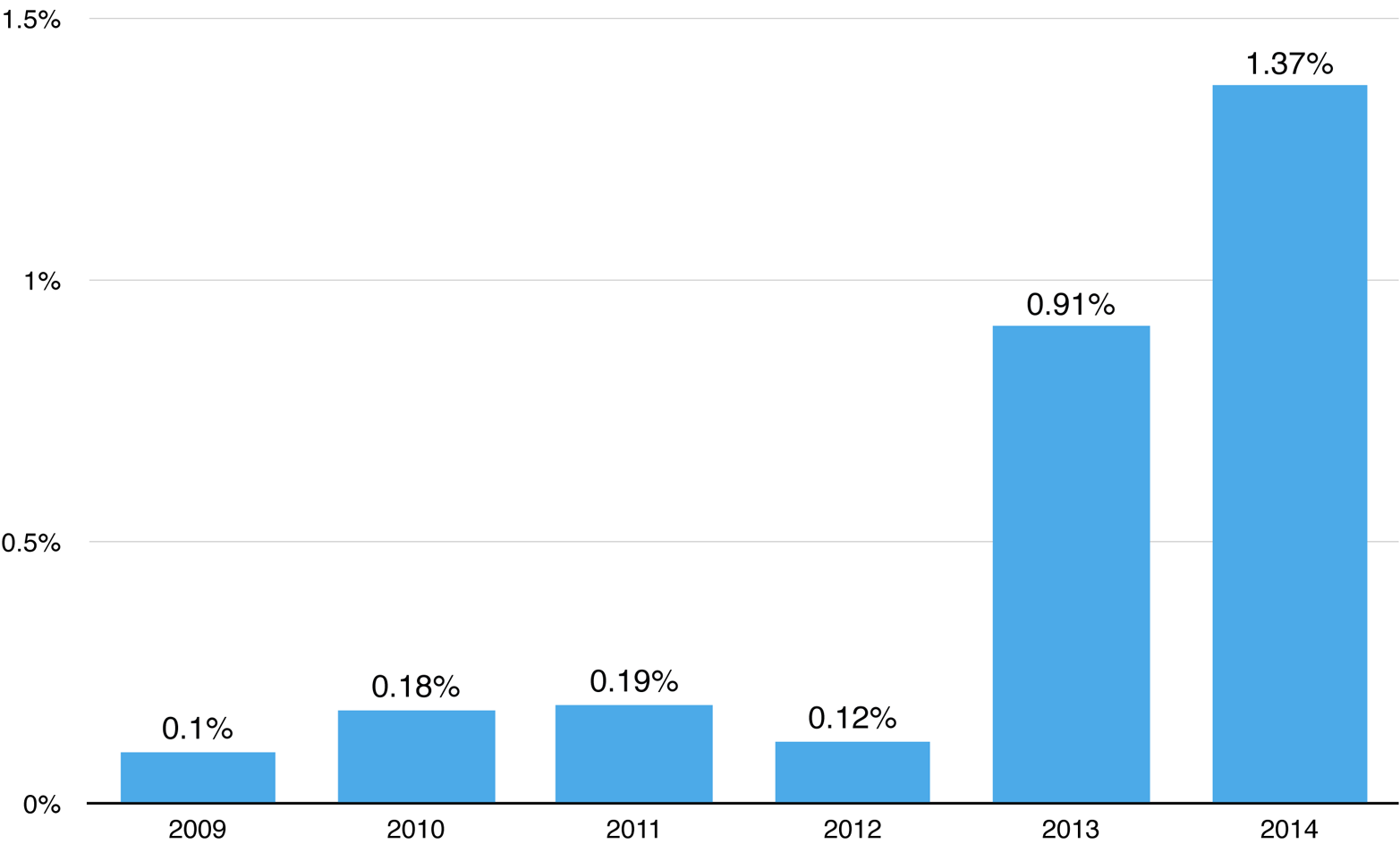

Moving away from Hardware proper…another area of the startup ecosystem that we’re following very closely is synthetic biology. Synthetic Biology refers to “the design and fabrication of components and systems that do not already exist in the natural world, or the re-design and fabrication of existing biological systems.” At O’Reilly, we’ve been following this space for a while; if you’re interested in in-depth quarterly reports, be sure to sign up for the BioCoder newsletter.

As of 2014, there are two new accelerators specific to Synthetic Biology. Y-Combinator also expressed interest in biotech in general, welcoming ten bio startups into its Winter 2014 class. 2014 saw YC accelerate two synthetic biology companies: Gingko Bioworks and Glowing Plant. SynBio Beta, a community site dedicated to tracking and facilitating the growth of the synthetic biology ecosystem, noticed the admissions, writing, “Biotech is no longer married to costly pharmaceutical and agricultural applications—or their heavy regulatory burdens—and is free to pursue non-traditional applications with consumer-facing businesses. By leveraging continuously improving infrastructure and technologies, biotech startups such as Glowing Plant are becoming increasingly lean, highly scalable, and getting products to market more quickly.”

Looking at AngelList data for Synthetic Biology, we see 44 companies in total. The first 12 joined AngelList in 2012; there has been no clearly accelerating trend yet. We saw 7 in 2013, 16 in 2014, and 9 so far in the first half of 2015. Fourteen of the companies have raised venture dollars: $179.8 million in total. Ten are based in San Francisco; the rest are scattered across the country.

The sectors that these companies focus on run the gamut. The largest subclassifications are bioinformatics, nanotechnology, and biofuels, but the sample size is small. We look forward to covering how this space continues to develop in future Hardware by the Numbers reports.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this brief overview of some of the trends that we’ve observed in the hardware ecosystem, and will join us at Solid to hear from the expert innovators who are driving these industries.