Designing for social impact

Use design to solve usability and communication issues in the social space at scale

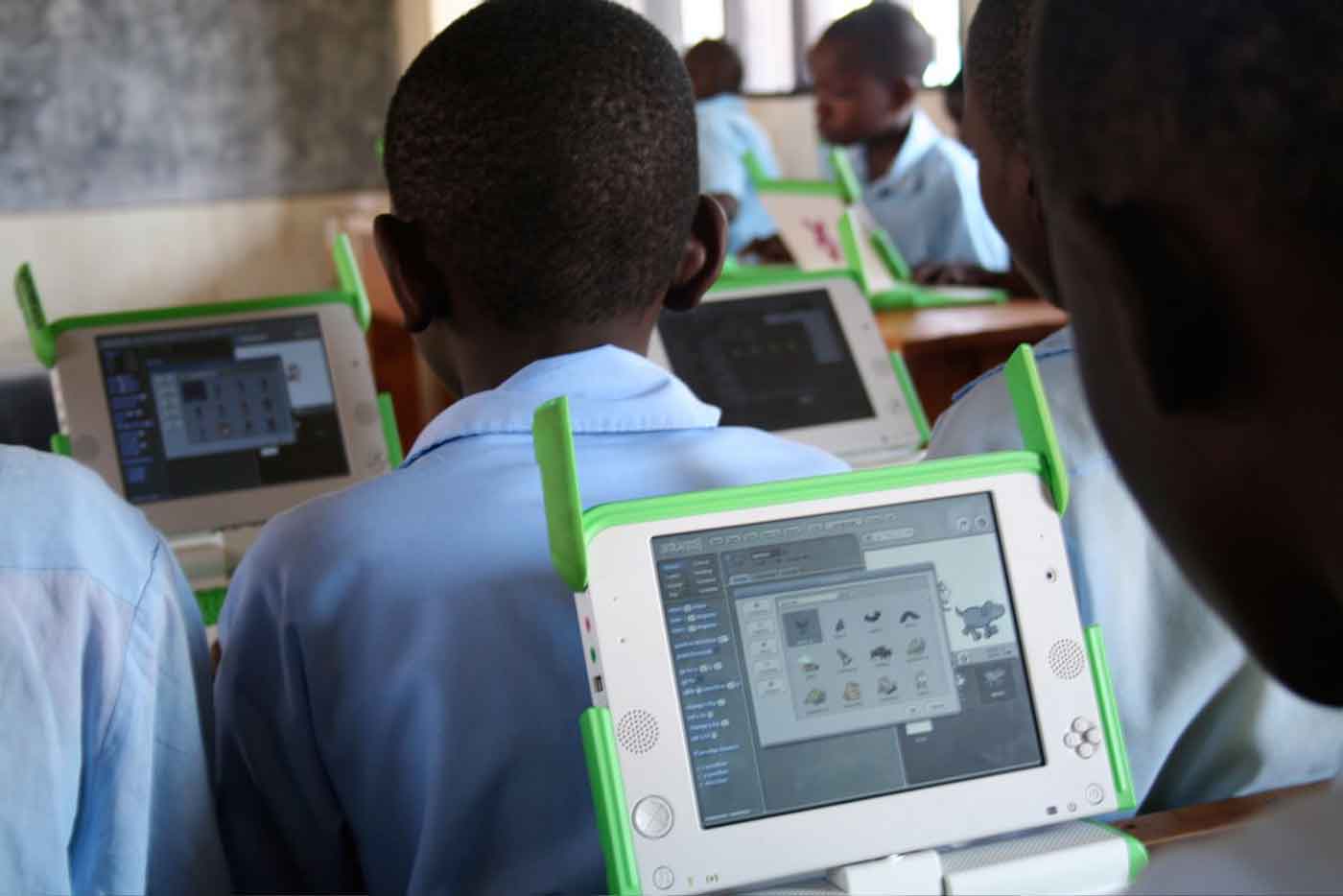

Kids with laptops (source: O'Reilly)

Kids with laptops (source: O'Reilly)

During the 2000 United States presidential election, product designers and developers discovered an uncomfortable truth about our nation. American democracy, long held up as a beacon for others to follow, was susceptible to “user error.” As the stories of hanging chads, bad ballot layouts, and unclear instructions unfolded, it became clear that the election process contained quite a few bugs from an end-user perspective. Dana Chisnell, the creator of Field Guides for voting, was inspired to fix such problems the best she knew how—by applying user-entered design practices. Until the 2000 presidential election, she pointed out that a “usable” ballot was one that was readable by the machines that count them. But, the “hanging chad” phenomenon brought to everyone’s attention the role that user error (or rather, terrible design) can play in affecting outcomes and a nation at large. This is but one example of how the design of simple things has an impact far beyond its immediate surroundings. It’s part of a clear case that more comprehensive, thoughtful design can have more predictable, measureable effects on our world at large.

More and more, designers of all stripes seek projects and organizations that have a mission to serve the greater good at their core. Partly it stems from an innate desire to use our skills to their highest potential. It also reflects broader trends in design and tools that make it possible for us to tackle problems that we observe in society, measure their root causes, and more quickly and efficiently test what works to create positive change. The inherent “usability” issues within the systems that surround social impact objectives are becoming more evident. Design increasingly has the ability to run programs at scale that address more systemic issues that arise from a lack of infrastructure or overly complicated regulation.

This golden opportunity for design in the social space is already gaining momentum. The ability to scale offered by digital technology is a part of what makes many social-impact projects finally make sense. They can reach many people, more effectively, more measurably. The pressures of globalization in a connected world also fuel the drive toward social-impact–focused work, along with the visibility of how old ways of handling social problems have failed. The technology space has embraced approaches that make social-impact projects manageable and measurable. Designers who are deeply curious to learn about what is effective at scale can find very fertile ground in governmental, philanthropic, and healthcare domains.

Let’s look at how designing for social impact differs from more commercial work, and share some lessons from the field about what works and that for which we should be alert.

What’s Different About Designing for Social Impact?

Designers looking to move into the social-impact realm will find that their education, training, and tools will be very relevant, and the work will appear similar to commercial product and services projects. However, there are four key differences in work that aims to achieve objectives for social good:

- Design for everyone

- Targeting or prioritizing specific user groups can be challenging or counterproductive.

- The importance of being empathetic

- Empathizing with users and user research must be especially culturally sensitive and might require different approaches.

- Behavior change is a focus

- Getting to more positive social outcomes involves more deeply psychological motivations and barriers than changing purchasing patterns or task efficiency.

- Risk tolerance is low

- The ability to “make mistakes” or chase losing hypotheses is low because there is more than money at stake.

Designing for “Everyone”

In a commercial context, targeting your product can often be the secret to success. The roll-aboard suitcase is the classic example of a product designed for the needs of a niche audience: flight attendants. Roll-aboards are easy to move through the airport, fit neatly in overhead compartments, and hold just enough for a short trip. Those needs also overlapped with many other travelers, which guaranteed its market triumph.

When we design for certain social outcomes, we often don’t have the luxury of targeting our designs. Our civic institutions are meant for all citizens, so to target only those easiest to reach will interfere with your ultimate goal and create advantages for those who least need them. Imagine an information system for a city that only targeted those residents who are homeowners and (improperly) seen as most likely to research what new construction projects are occurring in their communities. This group is likely to become strong defenders of their immediate surroundings, ensuring that dangerous or polluting projects are built only in poorer areas of the city. Civic engagement can’t be considered a success if it only serves to create more NIMBYism within well-off communities.

This problem, known as information asymmetry, is a very real one for product and service designers working to create positive social change. “Early adopters” in a commercial market are highly-valued for their ability to evangelize and popularize a product so that many more can enjoy them. Indeed, many early adopters will even pay a premium for a product whose price can be reduced when it is scaled to the market as a whole. But what happens when tools that are designed to remind people to vote are only available to a segment of the market?

Rather than targeting a part of the market that is most easily reached, it can be more useful and powerful to develop a variety of “on-ramps” for different types of people who have more or less agency. This helps to ensure that those who need help the most can obtain it. Understanding the unique challenges of a wide array of people will help you design solutions that overcome inequality and asymmetry rather than ignoring them to ensure adoption.

Fully embracing the uniqueness of our relationships means abandoning the most durable (and offensive) marketing metaphor of the last fifty years: the funnel. While all kinds of optimization are possible in funnel-oriented thinking, it is by definition impersonal treating everyone in a predefined process as of undifferentiated equal value. Organizing meaningful opportunities to engage over time allows each person more agency to create his or her own experience and deepen his or her engagement over time leading to more opportunities to engage over the lifetime of the relationship.

Michael Slaby,

Obama for America

There is still value in picking certain groups to target solutions, especially in the early days of a project. However, the choice of target might actually be a group that is harder to reach but who will benefit most from your work.

The Importance of Being Empathetic

Historically, social-impact projects have often been efforts that were executed with little visibility or attention placed on what the target audience actually desired, what motivated them, and what barriers they faced. What better environment to interject design! The practice of human-centered design places great value on understanding and empathizing with that audience in order to generate effective solutions.

First, a note of caution about embracing social change work: as many designers contemplate taking on work that drives social outcomes, it can be tempting to imagine yourselves as a type of Robin Hood—courageous crusaders who will take on the system on behalf of the people. The most critical assets for designers to develop are an open mind and curiosity about learning “what works” and building upon that. This is in contrast to imposing top-down ideas on others. Or, if you’re looking for a “disruptive” approach, be sure to include those who will live with those disruptions on a daily basis to avoid, well, disruption.

As Matt Hammer, executive director for Innovate Public Schools and a life-long community organizer shared, “It’s not about speaking truth to power. Power knows the truth. You need provoke people to know what they should have access to and how to obtain it from the system.” He and other social workers emphasize the need to make systems that create self-agency and autonomy within communities, not simply band-aids. Beware of an attitude that assumes that by simply applying design to a problem, the people who are affected will benefit. Although this might always be a concern for designers, when the effect of your work is about more than delighting people, you owe it to your audience to respect their autonomy and to ensure that they feel entitled to that which, by all rights, is theirs.

User research in this domain is especially critical and serves two functions. One is to help the designers understand how people think and behave. More important, though, it is to include those who will use a solution in its creation. A fourteenth-century political model is often quoted by those working in social justice or community organizing: “Nothing about us, without us.” You might recognize a version of this thinking in the phrase, “no taxation without representation.” By including those you serve in creating solutions, you are helping to create self-agency and buy-in within populations that previously will have been shut out of their own solutions, either because of political processes, inequality, or a lack of expertise. For example, diabetics looking to take control of their health might be given very simple tools, because as one client put it, “a smart meter makes a dumb patient.” We can find this type of paternal attitude about the capabilities of those being served in many domains, and designers should be on the look out for such views and work to subvert them.

Good designers will bring the tools they use every day to these projects and will succeed if they can remember to keep their efforts focused on helping people help themselves rather than creating things “for” people. Social-impact work is a fantastic opportunity to use co-design techniques to design with, not for.

It’s also critical for designers to distinguish between understanding and empathizing with those we seek to serve and feeling sorry for them. Even though this distinction might seem obvious, the temptation to position yourself as the answer to a problem is strong; after all, wanting to do some good is probably what attracted you to the social-impact space to begin with. During the research stage of a project on insulin pumps for children, I once observed colleagues openly expressing sorrow at how children’s lives had been negatively affected during user interviews. What was striking was that none of the children, and indeed few of the parents, saw themselves as “victims” of a disease. Rather, theirs was a specific life with specific conditions that needed to be managed. Respecting the agency and abilities of those who will benefit from your product or service can be the difference between understanding the real psychology at play and failure.

Design for Behavior Change

Design, especially interaction design, has been described as using human behaviors to affect choices. This is especially true in social-impact projects. Enticing someone to buy a commercial product might mean appealing to someone’s vanity or deep-seated desire to be entertained rather than challenged. Enticing new, lasting patterns that lead past short-term benefits to longer-term outcomes requires different tools.

Consider the challenge of tackling voter turnout. Voter turnout in the last election hit a 70-year low, at 36 percent. This is in a time when vitriolic debate on both sides seems to be at an all-time high. Why, then, are those angry voters not turning up in droves? It turns out that voters are often apathetic in a very specific way. Jodi Goldberg, a parent organizer in Milwaukee calls these types of people “blithely trusting” of the system and others in it. Voters assume that other people will take the time and energy to turn up at the polls and things will generally work out. Or, they might be demotivated, assuming that all hope is lost, and their time and energy is best spent on their families and personal survival.

Apathy isn’t the only challenge that designers in the area of social impact face; fear is a very real factor as well. Take the case of a gay man at risk of contracting HIV. Although he might know that there are steps to take to protect himself and others, the fear of facing the knowledge that he might be infected is a powerful psychological force that cannot be ignored. Designers and researchers must be diligent about identifying the psychological forces at work, and tying the tools and information in products to them specifically.

In the end, a dedication to finding evidence-based theories of change that can be measured objectively is critical.

Design for Behavior Change is a large topic unto itself. As noted earlier, behavioral economics has provided a strong research base on how people actually act and react to forces in their lives. Rather than being rational actors that many early economic models assumed, people are people, and thereby irrational. Yet, irrational does not mean completely unpredictable. There are many researchers and designers who have begun to bridge what we know about our psychology with design best practices. Stephen Wendel’s book Designing for Behavior Change: Applying Psychology and Behavioral Economics is a great place to begin learning what behavioral economics and psychology have to teach us about how people make decisions.

Another good resource is the “lenses” Dr. Don Lockton has developed for designers to use. Likewise, Stephen Anderson has several useful things to say about the topic on his website. BJ Fogg at Stanford has several tactics and practices that designers can use that have been proven to work in many contexts; you can find them at http://behaviormodel.org. Designers can also benefit from this primer on psychology and motivation, created by me and Janna Kimmel.

The single most illuminating concept I have found in the work of behavioral economists and those in the field of psychology is the importance of intrinsic motivation in changing behavior. Extrinsic motivation relies on external things, (i.e., compensation), to achieve the desired behavior. Intrinsic motivation occurs when a person has internalized the benefits of a behavior change and has the agency and desire to achieve them. External motivators are great for helping people perform routine tasks faster. But changing behavior and making it stick requires internal motivation that unlocks the creativity and desire to change.

Systems Change, Service Design

When we design commercial products or services, one of the first things we do is assess the systems and infrastructure that will aid and abet our efforts. In fact, much of the design efforts of the 1990s and 2000s had to do with getting those systems aligned with the mental models and needs of consumers. Enterprise software design focuses on creating digital ecosystems for businesses that need some stability of operations and value infrastructure’s role in providing that stability.

In domains focused on social good, those ecosystems aren’t always available to designers. “Government-owned infrastructure isn’t often stewarded well. One of the problems in Detroit, for example, is aging infrastructure,” says Tiffani Bell of The Detroit Water Project, an effort to crowd-fund payment of water bills for those who otherwise face having their water cut off. Her project steps in where the city’s systems stop working to avoid catastrophe for those citizens expected to live without the basic necessity of water. Bell isn’t crying foul at a system that penalizes poor residents; she’s acknowledging that the Detroit city system is so badly damaged that its citizens must help themselves.

Often the aim of social-impact projects is to replace, decode, or enhance existing systems that were never designed for consumers to use. Such systems were, as was noted at the beginning of this report, generally designed to comply with regulation. And so, as designers we find ourselves not just functioning as human-computer interface designers, but as designers of an interface to systems that never saw “users” coming.

Risk Tolerance Is Low

Compounding this situation, especially in the civic arena, is a very low tolerance for risk. Apple can afford to ship a product that might not work entirely as expected at first; it knows that the delight it does generate and the strength of its brand will placate consumers for a while. The United States government had no such brand to lean on when it launched HealthCare.gov in 2012. The initial phases of that launch were not a surprise to anyone who has been involved in large-scale software development. One of the key flaws of the system resulted from an architectural decision to require users to create an account to shop for insurance plans, resulting in serious performance issues during a high-visibility launch. Governmental projects have an especially low tolerance for such issues when the stakeholders are elected officials who live in the public eye. Politicians are also vulnerable to partisan opposition who will magnify failures for their own gain. A more agile approach to development might have identified such performance issues earlier on, giving the team time to adjust without scrutiny. It appears that the program has succeeded despite the bumpy start, but not every mistake is recoverable.

In public projects, the issue of procurement and financing is especially challenging. Typically, there is a blind, open-bidding period tied to a very specific Request for Proposal (RFP), outlining specific features, phases, deadlines, and dependencies. This leads to the worst of all worlds: fixed scope, costs, and timeline. Managing risk takes the form of an increasing set of change orders against a master plan that is no longer relevant. Enter Agile development methods. Dana Chisnell says, “Agile was made for government.” As public projects become more of a focus for digital designers and developers, they will need to evolve how work is specified, bid, and managed.

18F is an organization within the General Services Administration that is attempting to bring the craft of digital design and development into the government itself. Hillary Hartley, deputy executive director and cofounder of 18F, says the goal is to “help government do for itself again” rather than rely solely on contractors and procurement processes that work at odds with the ultimate goal of serving people well with stuff that works. The transition to new ways of framing goals and planning work will not be easy, but it is a key part of designing for social impact.

Lessons from the Field

Having looked at some of the forces that make designing for social impact different from designing in a commercial context, we can now look at several emerging practices and lessons learned in the field by several practitioners. These are offered as a series of guiding principles about how the aforementioned unique challenges can be met by teams creating products and services that deliver positive outcomes.

1. Garner an Invitation

As discussed in the first section of this report, work in the realm of social good often means needing to address a wide, even public, audience whose orientation to the topic or task will vary, and can’t easily be de-scoped from the target market.

In this situation, it is wise to remember the advice about first impressions. No one person, brand, or message appeals to everyone, and to come close is to become a bland purveyor to all. In some communities, efforts to “help” are met with a great deal of well-earned skepticism. Many social-impact projects contain a mental model of the well-heeled savior come to “fix” things for others, a model that can be detrimental to connecting with every population.

So, how then do we as designers become respected and valued by groups whose cultural context is very different from our own? How do we gain trust with a group of people who are not predisposed to trust outsiders?

Begin by acknowledging the networks of people who are already working in or around the topic and create a partnership strategy that is mutually beneficial. I interviewed a domestic violence prevention counselor, who for this discussion we will call Marta, who works specifically with the Latino community. She described her first years of service as an attempt to address the effects of violence on the women she met, helping them to put their lives back together as best they could. Over time, her organization has moved toward a strategy of prevention services that target the whole family. As a result, she serves as a counselor and guide to women around issues as diverse as family planning, obtaining food stamps, choosing schools, and finding employment. Marta is a key hub in her local influence network.

Anyone focused on these issues can gain entry by working with social workers like Marta, to help her community to develop information and tools that she can share and endorse. Community centers, counselors, religious leaders, and other people embedded in a community are often seeking out reputable, useable tools and information to share with those whom they serve. For designers, these leaders represent a way to garner an introduction to an audience whose trust will not be given to outsiders easily, if at all.

Partnerships in this type of ecosystem are also critical to success. Understanding how to create and support key “evangelists” for your cause is crucial to the distribution and acquisition of end users. It’s also important to shift your focus from seeing groups involved in similar or even identical work as competition and view them instead as a special kind of audience that can be cultivated for mutual benefit. This might mean equipping them through a “train the trainer” model where they become expert guides to introduce tools, and give those tools a halo of trust within a community. It can also mean that a specific version of tools is needed to enable a “street team” to use data and information more naturally. As you lay out your approach to cultivating audiences, don’t leave out community leaders as an audience to serve, as well.

The Field Guides for voting are an excellent example of how a project can become more scalable and impactful when the “users” considered are part of the system itself, not simply the end users. The project began as research into how specific language used in ballots affects voters. The final product is more of a series of playbooks for those who run elections. They contain practical guidance about everything from creating effective ballots to guiding people through the polling place to ensure that voting is “functional” for people, not just machines. By tackling the right audience—those who run elections, not voters themselves—the effects of the work will be felt by end users, the voters, more deeply.

2. Meet Them Where They Are…On-the-Go, Offline

Designing for a broad audience often means reaching people who do not live their lives attached to small electronic devices. Although the statistics for mobile devices and smartphones shows continuing growth, I am consistently reminded in doing social impact work that a large part of the audience (and often the neediest) is not digitally connected.

GreatSchools tackled this problem by focusing on printed information about schools as a key part of a distribution strategy. Print materials are a way for people to take your info “to go” easily and refer to at times when they might have more capacity to think differently or more deeply about a topic. Print also lends itself well to presenting data for comparison or longer-term usage.

In Milwaukee, thousands of school guides covering the area can be spotted all over the city, from hair salons to the back seats of cars, as families consider which schools to choose for their children. It also serves as a way to signal how important that issue is for the city at large and provides a visual cue to who is part of the conversation.

Print also lends itself to being discovered in some of the trusted partner channels that should be part of your strategy. GreatSchools has partnerships with many organizations such as health clinics or the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Counselors in partner organizations gladly hand out printed information (as well as links to the website) to those who are seeking affordable housing or health assistance. Because housing and school attendance are two tightly linked topics, a partnership that turns the HUD workers into school information evangelists is natural and a win-win for everyone. Designers should research and consider how their work can and should exist offline for the part of the audience who are not connected, yet deeply in need of assistance.

Finally, SMS messaging has begun to show returns as a channel for many low-income families. In a partnership between the San Francisco Unified School District and Stanford University, a series of short texts aimed at helping parents grow early literacy skills in kids showed major gains through a simple medium that has deep penetration in low-income and non-English-speaking households.

As you consider getting your tools out to a wide variety of people, be sure to ask how you can best engage those with limited digital access.

3. Imagine Feeding the Trolls

Whereas the best advice on the Internet is probably “don’t feed the trolls,” as a designer, this might be advice you need to ignore. You need to understand troll behavior to defend against it. In a commercial context, if your product doesn’t work for a part of the market, they simply won’t buy it. However, in the context of serving social good, alienating someone can fuel a counterargument to yours that can be devastating, not just detracting.

Brandon Harris, formerly of Wikimedia, has thought a lot about designing systems that can’t easily be hijacked for a specific agenda. He counsels designers to make a “Troll Persona” whose motives and tactics are likely to fall into the extreme. This type of white-hat interaction design is akin to operational security efforts to proactively hack systems to find weaknesses that can and will be exploited.

Key points of failure for trolls will tend to be commenting systems, rating systems, or other places where communal voices can be heard. In the case of Wikipedia, there is an entire network of quite involved rules, social norms, and committees that police the space and attempt to keep the playing field level.

A recent news story revealed a disturbing, though not entirely surprising, security vulnerability: drug delivery pumps in hospitals. Although it’s understandable that manufacturers assumed that hospitals and medical equipment were not likely targets for hackers 10 years ago, in today’s technology environment we can’t afford that level of implicit trust. Design teams need to think about where to defend their users and secure products whose existence might be contentious or tempting to some elements of society.

4. Appeal to Identity, and Make a Plan

Todd Rogers, a psychology researcher from Harvard, has completed some fascinating work on understanding motivation and behavior change, especially in the realm of “get out the vote” efforts. His work during the 2012 election cycle netted several important findings for those of us engaged in social-impact work.

First, he discovered that appealing to a person’s identity to be a certain kind of person is more motivating than being credited for doing a task. For many years, voters have been given stickers with the “I Voted!” message on them. According to Roger’s findings, those who are encouraged to see voting as part of their identity rather than just something they do are more likely to turn up to vote. Stickers now proclaim “I’m a Voter!” in a small nod to this finding. Thinking about ways to turn your desired behaviors into an identity is a technique that designers can’t ignore.

Additionally, voter turnout increased substantially when voters were prompted to make a specific plan for how and when they would vote. By prompting people to name a specific time, identify where their polling place was, and how they would get there, get-out-the-vote efforts increased participation. Rogers’ TED talk on what he learned is another good primer for designers wanting to more deeply understand how psychology and behavior change are related.

This type of subtle shift in framing is part of a growing trend for designers, especially around behavior change projects. As we will discuss later, designers need to become adept creators and experimenters around specific language, framing, and context that ultimately make the difference in measurable impact.

5. Use Data to Inform and Provoke Actions

Every good story needs a crisis; every design needs to create the right tension in the minds of their users to succeed. One lesson from the front lines of community organizing is the idea of showing “the fear, followed by the hope.” Innovate Public Schools is an organization working in the San Francisco Bay Area to get Latino and African-American families to demand better quality schools for their kids, who suffer at the hands of a sizable achievement gap. What their organizers have learned is to mine data about schools to find stark examples of disparity and inequity and display them clearly as simple comparisons or rankings of different options. Innovate aims to help families to choose schools that serve all kids equally, so a side-by-side comparison is the most effective way to begin a conversation. Parents’ attention is most easily grabbed by showing them a disparity that they’ve maybe sensed or wondered about but never been able to pinpoint.

After you have found the provocative data point, or “the fear,” it is important to follow that up with “the hope” or the options that will lead to better outcomes for the person. This might mean showing those schools where Latino kids are well served, or showing ways parents at their school can advocate for their kids more effectively. Simply laying out the fear without the hope will not lead to the intrinsic motivation among your audience to take charge of their destinies and become active participants in your social-good domain.

It can be challenging to roll up data with all of its nuances, caveats, and glitches, but this can be the area where design can play the biggest role in driving impact. Just as an editor must help provide a headline that pulls people into a complicated story, so must designers work on visualizing key takeaways from a set of data that can be analyzed more deeply. Designers must partner with data scientists and analysts who are close to the data to develop meaning from data that is both accurate and accessible.

6. Not Just What You Say, But How You Say It

Just as you become a more thoughtful wielder of data for social good, you must also become attuned to how people will use that data to ensure that your efforts really are in service of the social good, not the opposite.

In a study of rating systems around school quality, researchers presented a variety of visualizations to parents to understand which one they “liked” the best. A 1–10 scale, although overly precise, was seen as “better” to parents than a 3- or 5-point scale which might have been truer to the conclusions offered by the underlying data. However, an A–F scale was also valued, perhaps because it is familiar to parents and relates to the domain of education.

The study went beyond measuring preference and also probed parents how they might use each scale differently and a startling insight emerged. Even though parents liked both the 1–10 scale and the A–F scale, they overwhelmingly said they would choose to send their kids to a school that was an 8 out of 10, but not a school that was rated a B. This is important because those two ratings are identical in the underlying data but have radically different outcomes. If the aim of a ratings system is to help parents choose higher-quality schools, we need to understand how presenting data affects choice. In this case, schools rated an 8 or above are considered “quality” schools, so using an A–F system will be counterproductive. It’s worth noting that many states use an A–F rating system, because the outcome of such systems is to provide a picture of accountability to the public, not to drive consumer choice. In that case, letter grades may in fact be more useful as a signifier of performance.

Becoming attuned to learning how people use your information is a critical skill for working on social-impact projects. You need to learn how to measure the impact of your designs on the understanding and effect on specific tasks, not just preference.

7. Algorithms versus Legislation

As we noted at the beginning of this report, the design challenge you face might be to make the system itself more useful and usable. How can designers identify key components in a system—which is often people—that contain critical information but aren’t accessible?

Consider the rise of commercial tools designed and developed to make paying taxes more efficient and accurate. Even though the IRS publishes many forms and handbooks, those of us who are not CPAs find them impenetrable. By capturing the underlying logic and algorithms of the tax code and expressing them in sequential steps and diagnostics, software has made paying taxes for many people a simpler proposition. Taxes lend themselves very well to digitization because of the nature of calculations and finances. In this case, the challenge is daunting because of its scope, but it is relatively simple because the tax code is a sort of algorithm in and of itself.

However, what happens when there is no algorithm underlying the system? In Boston, a Code for America fellow, Joel Mahoney, undertook a project to digitize the enrollment criteria for public schools. He wanted to know if he could help families understand which schools they were eligible for based on new legislation. He began by creating a Google Maps visualization of schools within two miles of an address. The first design decision he faced was whether that distance was as the crow flies or as walking distance. As he dug deeper into the data, he discovered edge-cases such as the corner of a school being two miles from an address but not the school’s front door. As he worked with local government to create a digital system, it became clear that the legislation had not been created with digital tools in mind. Rather, the system was an old-fashioned list of addresses tied to schools, maintained by hand. As government becomes more digitally supported, the ability to translate laws into algorithms will become part of the design challenge.

8. Time-Shift and Demystify the System

One of the most challenging aspects of our infrastructure around social impact is its retail model of locations staffed with people without the retail level of service. Wendy Fong, working as a Code for America fellow in Mesa, Arizona, discovered that a big challenge for city residents was getting a hold of information about what was happening in government outside of the city hall, where people were expected to navigate between gathering information and expressing their opinions between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., in person. The app she created effectively collected data and made it available 24/7 via a computer. This simple time shifting and move toward self-service is a benefit that other industries realized long ago, but it represents a big opportunity for designers.

As noted earlier, simply moving toward a digital self-service model is a seductive silver bullet for governmental and nonprofit groups looking to save money. But, as we design for everyone, it’s critical to think about how you will also support those who can’t or don’t access digital services regularly. Tapping into community partners and other channels should be part of the approach.

In Atlanta, Tiffani Bell’s Code for America project focused on assisting city suppliers to cope with a complex set of rules meant to ensure fairness and avoid patronage in city government. These labyrinths of rules often lead to a system that is so difficult to understand, it unfairly aids a small set of operators who have command of what bids are available and how to game the system to win. Such information asymmetry—in which one party has more access to and understanding of data—can be a big counterforce to equity and social good. By making the latest bids on offer from the city an upfront part of the website, Bell’s work begins to break down the inequity to level the playing field.

Looking Forward

By now you should have a sense of how the landscape is different when you’re not working in a commercial domain and some of the key things to consider toward the goal of successfully delivering positive social change. Turning now to the future, there are several emerging developments about which designers and developers should be aware.

Mobilization as a Service and Self-Service Tools

We’ve seen how designing for public, healthcare, and philanthropic endeavors requires a special attention to your audience and what they require from a system intended to serve them. Working at the intersection of convoluted systems and people is fertile territory for design.

Increasingly, however, the needs of these sectors will stabilize, just as they have in the commercial sector. As solutions emerge to meet the very specific demands of different systems and audiences, they will normalize and we’ll see more standard services targeted at social-impact efforts. Early progress can already be seen here. Nationbuilder.com and Civiceagle.com are two new Software as a Service (SaaS) platforms for political community organizing with turnkey solutions for keeping politicians and leaders connected with the public. POPVOX.com is a startup looking to make it easier for people to be aware of pending legislation and express their support or resistance publicly. These are private organizations with digital roots that are positioned as self-service tools for those who are deeply passionate about issues, not technology experts.

Patientslikeme.com is a platform for people to compare symptoms and obtain support for health challenges. Although many players in the healthcare market acknowledge that patients can and should have more efficacy and access to information about their illnesses, there’s little incentive for HMOs and insurers to invest in such tools. Patients Like Me began as a personal effort to support a family member with Lou Gehrig’s disease, and, like the roll-aboard suitcase, has turned out to be useful to many more people, all while existing entirely outside the “system.” So, as savvy designers enter the social-impact space, they will do what they’ve done elsewhere and share what works, creating a normalization of features and making it less expensive to create and maintain systems.

Evolving Roles, Growing Capability

As design becomes a bigger part of the intentional part of social-impact work, the roles within organizations will expand and evolve. Following are some examples of roles that can help alleviate pain points that organizations face today:

-

Design thinking for procurement and financial models that help manage risk, create more manageable RFPs, and create sustainability for products and services

-

Interaction and visual designers to bring the craft of design to bear on social projects, get beyond “functional” products, and help government do for itself again

-

Design technologists that can prototype ideas quickly and help make abstract ideas tangible and testable

-

Behavioral psychologists and design researchers to conduct upfront research, understand key barriers and motivations, and run fast-cycle research experiments

-

Design thinking to help inform, explore, and prototype policy options

Whether these roles are filled by working in-house or in social-impact-focused consultancies, it will be critical for designers to evolve their thinking about what success means and be deeply curious about the overall effect that the work has on those it seeks to benefit.

Designers are naturally predisposed to interdisciplinary teams and collaboration, and social-impact work demands this aptitude at even higher levels than commercial work. This work cannot be done in a standalone fashion. You must acknowledge others working in your space and engage multiple facets of large systems and many organizations to tackle the wicked problems underlying social change.

The Future of Impact

As we’ve looked at the current state of design for social impact, it’s clear that the context of design is very different. The financial models, target users, and risk tolerance all affect the way in which designers operate and how they evaluate success. The tools and skills of design are all highly relevant, however, and all designers will find that their abilities are immediately valuable in this new context.

By looking at the lessons learned by current practitioners in the space, we’ve seen that adapting some processes or approaches is necessary. This field holds a great deal of promise for designers, and we will need to continue to share our experiences and best practices to continue to drive the quality of our social outcomes and bring them to market more quickly.

The Social Impact Lifecycle

Even though different types of projects have specific audience, context, and content issues to wrestle with, a simple model of the lifecycle for social impact is useful to discuss here. The following diagram demonstrates a typical path for a user who engages with a system or product that has positive social outcomes as a goal:

First, the journey begins with attracting people to the issue, cause, or new benefit. Commercial projects understand this well; marketing is valued as a key part of brand and user experience (UX). When working in social-impact areas, this step might not be obvious to everyone involved, or they might have very limited ideas about awareness campaigns or other marketing basics. Designers can help organizations deeply understand their audience and bring a large number of levers to bear on attracting them, from social to search optimization.

Second, this model lays out the need to both inform and provoke people with information that is new, surprising, or agitating, with the goal being to get them to take action. As compared to an ecommerce model, the actions we are trying to provoke might meet with resistance or apathy, so designers must create tension in the minds of their audience that cannot be ignored. We will look at this more deeply a bit later when we look at emerging practices around data visualization. For those projects that are focused on delivering services, it might be less about provoking a response and more about communicating clearly about what the service is and how to take advantage of it.

Finally, this model acknowledges that social impact is often an ongoing cycle, in which people are provoked over time to take actions that add up to social impact. This is not to say that some types of impact can’t be had in a single moment or interaction, but those instances will be rare and hard to measure. Obama for America’s Michael Slaby describes this as a “ladder of engagement” on which people take incremental steps from signing up for information to donating money to becoming an organizer of others. The specifics of what your audience engages with over time will vary, but it is important to acknowledge that a cycle exists.

The ongoing climb of the ladder of engagement is not the only way people are involved. As Jess McMullin of Citizen Experience has found in his work, engagement can also be provoked by extreme crisis as with a parent who loses a child to an unfair system, which spawns awareness and engagement with something like #BlackLivesMatter. The role of personal crisis in creating deep engagement is another mode into which designers can tap.