Classifying traffic signs with Apache MXNet: An introduction to computer vision with neural networks

Step-by-step instructions to implement a convolutional neural net, using a Jupyter Notebook.

Road signs (source: Pixabay)

Road signs (source: Pixabay)

Although there are many deep learning frameworks, including TensorFlow, Keras, Torch, and Caffe, Apache MXNet in particular is gaining popularity due to its scalability across multiple GPUs. In this blog post, we’ll tackle a computer vision problem: classifying German traffic signs using a convolutional neural network. The network takes a color photo containing a traffic sign image as input, and tries to identify the type of sign.

The full notebook can be found here

In order to work through this notebook, we expect you’ll have a very basic understanding of neural network, convolution, activation units, gradient descent, NumPy, and OpenCV. These prerequisites are not mandatory, but having a basic understanding will help.

By the end of the notebook, you will be able to:

- Prepare a data set for training a neural network;

- Generate and augment data to balance the data set; and

- Implement a custom neural network architecture for a multiclass classification problem.

Preparing your environment

If you’re working in the AWS Cloud, you can save yourself the installation management by using an Amazon Machine Image (AMI) preconfigured for deep learning. This will enable you to skip steps 1-5 below.

Note that if you are using a conda environment, remember to install pip inside conda, by typing ‘conda install pip’ after you activate an environment. This step will save you a lot of problems down the road.

Here’s how to get set up:

- First, get Anaconda, a package manager. It will help you to install dependent Python libraries with ease.

- Install the OpenCV-python library, a powerful computer vision library. We will use this to process our image. To install OpenCV inside the Anaconda environment, use ‘pip install opencv-python’. You can also build from source. (Note: conda install opencv3.0 does not work.)

- Next, install scikit learn, a general-purpose scientific computing library. We’ll use this preprocess our data. You can install it with ‘conda install scikit-learn’.

- Then grab the Jupyter Notebook, with ‘conda install jupyter notebook’.

- And finally, get MXNet, an open source deep learning library.

Here are the commands you need to type inside the anaconda environment (after activation of the environment):

- conda install pip

- pip install opencv-python

- conda install scikit-learn

- conda install jupyter notebook

- pip install mxnet

The data set

In order to learn about any deep neural network, we need data. For this notebook, we use a data set already stored as a NumPy array. You can also load data from any image file. We’ll show that process later in the notebook.

The data set we’ll use is the German Traffic Sign Recognition Benchmark (J. Stallkamp, M. Schlipsing, J. Salmen, and C. Igel. “The German Traffic Sign Recognition Benchmark: A multi-class classification competition.” In Proceedings of the IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, pages 1453–1460. 2011.).

This data set consists of 39,209 training samples and 12,630 testing samples, representing 43 different traffic signs—stop signs, speed limits, various warning signs, and so on).

We’ll use a pickled version of the data, training.p and valid.p.

Each image in the dataset is 32*32 size with three channel (RGB) color, and it belongs to a particular image class. The image class is an integer label between 0 and 43. The ‘signnames.csv’ file contains the mapping between the sign name and the class labels.

Here’s the code for loading the data:

import pickle

# TODO: Fill this in based on where you saved the training and testing data

training_file = "traffic-data/train.p"

validation_file = "traffic-data/valid.p"

with open(training_file, mode='rb') as f:

train = pickle.load(f)

with open(validation_file, mode='rb') as f:

valid = pickle.load(f)

X_train, y_train = train['features'], train['labels']

X_valid, y_valid = valid['features'], valid['labels']

We are loading the data from a stored NumPy array. In this array, the data is split between training, validation, and test sets. The training set contains the features of 39,209 images of size 32 X 32 with 3 (R,G,B) channels. As a result, the NumPy array dimension is 39,209 X 32 X 32 X 3. We will only be using the training set and validation set in this notebook. We will use real images from the internet to test our model.

So X_train is of dimension 39,209 * 32 X 32 X 3. The y_train is of dimesion 39,209 and contains a number between 0-43 for each image.

Next, we load the file that maps each image class ID to natural-language names:

# The actual name of the classes are given in a separate file. Here we load the csv file which allows mapping from classes/labels to

# file name

import csv

def read_csv_and_parse():

traffic_labels_dict ={}

with open('signnames.csv') as f:

reader = csv.reader(f)

count = -1;

for row in reader:

count = count + 1

if(count == 0):

continue

label_index = int(row[0])

traffic_labels_dict[label_index] = row[1]

return traffic_labels_dict

traffic_labels_dict = read_csv_and_parse()

print(traffic_labels_dict)

We can see there are 43 labels for the 43 image classes. For example,

0 image class represents a 20 km/h speed limit:

{0: 'Speed limit (20km/h)', 1: 'Speed limit (30km/h)', 2: 'Speed limit (50km/h)', 3: 'Speed limit (60km/h)', 4: 'Speed limit (70km/h)', 5: 'Speed limit (80km/h)', 6: 'End of speed limit (80km/h)', 7: 'Speed limit (100km/h)', 8: 'Speed limit (120km/h)', 9: 'No passing', 10: 'No passing for vehicles over 3.5 metric tons', 11: 'Right-of-way at the next intersection', 12: 'Priority road', 13: 'Yield', 14: 'Stop', 15: 'No vehicles', 16: 'Vehicles over 3.5 metric tons prohibited', 17: 'No entry', 18: 'General caution', 19: 'Dangerous curve to the left', 20: 'Dangerous curve to the right', 21: 'Double curve', 22: 'Bumpy road', 23: 'Slippery road', 24: 'Road narrows on the right', 25: 'Road work', 26: 'Traffic signals', 27: 'Pedestrians', 28: 'Children crossing', 29: 'Bicycles crossing', 30: 'Beware of ice/snow', 31: 'Wild animals crossing', 32: 'End of all speed and passing limits', 33: 'Turn right ahead', 34: 'Turn left ahead', 35: 'Ahead only', 36: 'Go straight or right', 37: 'Go straight or left', 38: 'Keep right', 39: 'Keep left', 40: 'Roundabout mandatory', 41: 'End of no passing', 42: 'End of no passing by vehicles over 3.5 metric tons'}

Visualization

The following code will help us to visualize the images along with the labels (image classes):

# Exploratory data visualization

# This gives a better, intuitive understanding of the data

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.figure import Figure

# Visualizations will be shown in the notebook.

%matplotlib inline

#This functions selects one image per class to plot

def get_images_to_plot(images, labels):

selected_image = []

idx = []

for i in range(n_classes):

selected = np.where(labels == i)[0][0]

selected_image.append(images[selected])

idx.append(selected)

return selected_image,idx

# function to plot the images in a grid

def plot_images(selected_image,y_val,row=5,col=10,idx = None):

count =0;

f, axarr = plt.subplots(row, col,figsize=(50, 50))

for i in range(row):

for j in range(col):

if(count < len(selected_image)):

axarr[i,j].imshow(selected_image[count])

if(idx != None):

axarr[i,j].set_title(traffic_labels_dict[y_val[idx[count]]], fontsize=20)

axarr[i,j].axis('off')

count = count + 1

selected_image,idx = get_images_to_plot(X_train,y_train)

plot_images(selected_image,row=10,col=4,idx=idx,y_val=y_train)

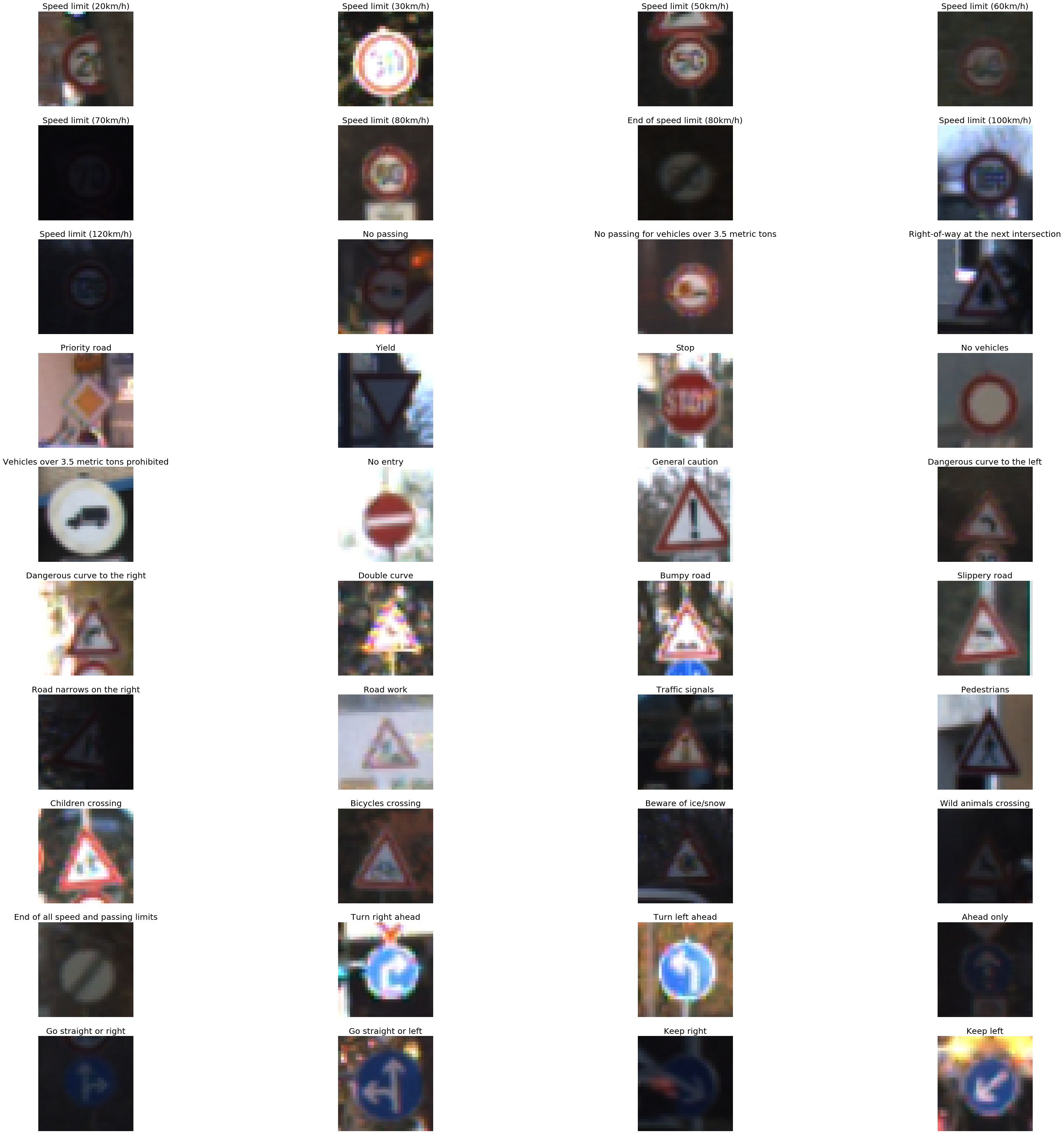

Here are the visualized traffic signs, with their labels:

Preparing the data set

X_train and Y_train make the training data set. We’ll employ real images for the purpose of testing.

You could also generate a validation set by splitting the training data into train and validation sets using scikit-learn (this is how you avoid testing your model on images that it’s already seen). Here’s the Python code for that:

#split the train-set as validation and test set from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split X_train_set,X_validation_set,Y_train_set,Y_validation_set = train_test_split( X_train, Y_train, test_size=0.02, random_state=42)

The image dimension order of MXNet is similar to Theano and uses the format 3X32X32. The number of channels is the first dimension, followed by height and width of the image. TensorFlow uses image dimension ordering of 32X32X3, i.e the color channels come last. If you’re switching from TensorFlow to MXNet this discussion of dimension ordering may be helpful. Below is the helper function to convert image ordering to MXNet’s 3X32X32 format from 32X32X3:

#change the image dimensioning from 32 X 32 X 3 to 3 X 32 X 32 for train X_train_reshape = np.transpose(X_train, (0, 3, 1, 2)) plt.imshow(X_train_reshape[0].transpose((1,2,0))) print(X_train_reshape.shape) #change the image dimensioning from 32 X 32 X 3 to 3 X 32 X 32 for validation X_valid_reshape = np.transpose(X_valid, (0, 3, 1, 2)) plt.imshow(X_valid_reshape[1].transpose((1,2,0))) print(X_valid_reshape.shape)

Building the deepnet

Now, enough of preparing our data set. Let’s actually code up the neural network. You’ll note that there are some commented-out lines; I’ve left these in as artifacts from the development process—building a successful deep learning model is all about iteration and experimentation to find what works best. Building neural networks is something of a black art at this point in history; while you might experiment to solve your particular problem, for a well-explored issue like image recognition, you’ll do best to implement a published architecture with proven performance. Here, we’ll build up a simplified version of the AlexNet architecture, which is based on convolutional neural networks..

The neural code is concise and simple, thanks to MXNet’s symbolic API:

data = mx.symbol.Variable('data')

conv1 = mx.sym.Convolution(data=data, pad=(1,1), kernel=(3,3), num_filter=24, name="conv1")

relu1 = mx.sym.Activation(data=conv1, act_type="relu", name= "relu1")

pool1 = mx.sym.Pooling(data=relu1, pool_type="max", kernel=(2,2), stride=(2,2),name="max_pool1")

# second conv layer

conv2 = mx.sym.Convolution(data=pool1, kernel=(3,3), num_filter=48, name="conv2", pad=(1,1))

relu2 = mx.sym.Activation(data=conv2, act_type="relu", name="relu2")

pool2 = mx.sym.Pooling(data=relu2, pool_type="max", kernel=(2,2), stride=(2,2),name="max_pool2")

conv3 = mx.sym.Convolution(data=pool2, kernel=(5,5), num_filter=64, name="conv3")

relu3 = mx.sym.Activation(data=conv3, act_type="relu", name="relu3")

pool3 = mx.sym.Pooling(data=relu3, pool_type="max", kernel=(2,2), stride=(2,2),name="max_pool3")

#conv4 = mx.sym.Convolution(data=conv3, kernel=(5,5), num_filter=64, name="conv4")

#relu4 = mx.sym.Activation(data=conv4, act_type="relu", name="relu4")

#pool4 = mx.sym.Pooling(data=relu4, pool_type="max", kernel=(2,2), stride=(2,2),name="max_pool4")

# first fullc layer

flatten = mx.sym.Flatten(data=pool3)

fc1 = mx.symbol.FullyConnected(data=flatten, num_hidden=500, name="fc1")

relu3 = mx.sym.Activation(data=fc1, act_type="relu" , name="relu3")

# second fullc

fc2 = mx.sym.FullyConnected(data=relu3, num_hidden=43,name="final_fc")

# softmax loss

mynet = mx.sym.SoftmaxOutput(data=fc2, name='softmax')

Let’s break down the code a bit. First, it creates a data layer(input layer) that actually holds the dataset while training:

data = mx.symbol.Variable('data')

The conv1 layer performs a convolution operator on the image, and is connected to the data layer:

conv1 = mx.sym.Convolution(data=data, pad=(1,1), kernel=(3,3), num_filter=24, name="conv1")

The relu2 layer performs non-linear activation on the input, and is connected to convolution 1 layer:

relu2 = mx.sym.Activation(data=conv2, act_type="relu", name="relu2")

The max pool layer performs a pooling operation (dropping some pixels and reducing image size) on the previous layer’s output (relu2).

pool2 = mx.sym.Pooling(data=relu2, pool_type="max", kernel=(2,2), stride=(2,2),name="max_pool2")

A neural network is like a Lego block—we can easily repeat some of the layers (to increase the learning capacity of model)— and then follow them with a dense layer. A dense layer is a fully connected layer, in which every neuron from the previous layer is connected to every neuron in the dense layer.

fc1 = mx.symbol.FullyConnected(data=flatten, num_hidden=500, name="fc1")

This layer is followed again by a fully connected layer with 43 neurons, each neuron representing a class of the image. Since the output from the neuron is real valued, but our classification requires a single label as output, we use another activation function. This step makes the output of one particular neuron (out of 43 neurons) as 1 and remaining neurons as zero.

fc2 = mx.sym.FullyConnected(data=relu3, num_hidden=43,name="final_fc") # softmax loss mxnet = mx.sym.SoftmaxOutput(data=fc2, name='softmax')

Tweaking training data

A neural network takes a lot of time and memory to train. We’re going to split our data into minibatches of 64, not just so that they fit into memory but also because it enables MXNet to make the most of GPU computational efficiency demands it (among other reasons).

We’ll also normalize the value of the image colors (0-255) to the range of 0 to 1. This helps the learning algorithm to converge faster. You can read about the reasons to normalize the input.

Here’s the code to normalize the value of the image color:

batch_size = 64

X_train_set_as_float = X_train_reshape.astype('float32')

X_train_set_norm = X_train_set_as_float[:] / 255.0;

X_validation_set_as_float = X_valid_reshape.astype('float32')

X_validation_set_norm = X_validation_set_as_float[:] / 255.0 ;

train_iter =mx.io.NDArrayIter(X_train_set_as_float, y_train_extra, batch_size, shuffle=True)

val_iter = mx.io.NDArrayIter(X_validation_set_as_float, y_valid, batch_size,shuffle=True)

print("train set : ", X_train_set_norm.shape)

print("validation set : ", X_validation_set_norm.shape)

print("y train set : ", y_train.shape)

print("y validation set :", y_valid.shape)

Training the network

We are training the network using GPUs, since it’s faster. A single pass-through of the training set is referred to as one “epoch,” and we are training the network for 10 epochs “num_epoch = 10”. We also periodically store the trained model in a JSON file, and measure the train and validation accuracy to see our neural network ‘learn.’

Here is the code:

#create adam optimiser

adam = mx.optimizer.create('adam')

#checking point (saving the model). Make sure there is folder named models exist

model_prefix = 'models/chkpt'

checkpoint = mx.callback.do_checkpoint(model_prefix)

#loading the module API. Previously mxnet used feedforward (deprecated)

model = mx.mod.Module(

context = mx.gpu(0), # use GPU 0 for training if you dont have gpu use mx.cpu().

symbol = mynet,

data_names=['data']

)

#actually fit the model for 10 epochs. Can take 5 minutes

model.fit(

train_iter,

eval_data=val_iter,

batch_end_callback = mx.callback.Speedometer(batch_size, 64),

num_epoch = 10,

eval_metric='acc', # evaluation metric is accuracy.

optimizer = adam,

epoch_end_callback=checkpoint

)

Loading the trained model from the filesystem

Since we have check-pointed the model during training, we can load any epoch and check its classification power. In the following example, we load the 10th epoch. We also set the binding in the model loaded to training as false, since we are using this network for testing, not training. Furthermore, we reduce the batch size of input from 64 to 1 (data_shapes=[(‘data’, (1,3,32,32))), since we are going to test it on a single image.

You can use the same technique to load any other pre-trained machine learning model:

#load the model from the checkpoint , we are loading the 10 epoch

sym, arg_params, aux_params = mx.model.load_checkpoint(model_prefix, 10)

# assign the loaded parameters to the module

mod = mx.mod.Module(symbol=sym, context=mx.cpu())

mod.bind(for_training=False, data_shapes=[('data', (1,3,32,32))])

mod.set_params(arg_params, aux_params)

Prediction

To use the loaded model for prediction, we convert a traffic sign image (Stop.jpg) into 32 32 3 (32 * 32 dimension image with 3 channels) and try to predict their label. Here’s the image I downloaded.

#Prediction for random traffic sign from internet

from collections import namedtuple

Batch = namedtuple('Batch', ['data'])

#load the image , resizes it to 32*32 and converts it to 1*3*32*32

def get_image(url, show=False):

# download and show the image

img =cv2.imread(url)

img = cv2.cvtColor(img, cv2.COLOR_BGR2RGB)

if img is None:

return None

if show:

plt.imshow(img)

plt.axis('off')

# convert into format (batch, RGB, width, height)

img = cv2.resize(img, (32, 32))

img = np.swapaxes(img, 0, 2)

img = np.swapaxes(img, 1, 2) #swaps axis to make it 3*32*32

#plt.imshow(img.transpose(1,2,0))

#plt.axis('off')

img = img[np.newaxis, :] # Add a extra axis to the image so it becomes 1*3*32*32

return img

def predict(url):

img = get_image(url, show=True)

# compute the predict probabilities

mod.forward(Batch([mx.nd.array(img)]))

prob = mod.get_outputs()[0].asnumpy()

# print the top-5

prob = np.squeeze(prob)

prob = np.argsort(prob)[::-1]

for i in prob[0:5]:

print('class=%s' %(traffic_labels_dict[i]))

predict('traffic-data/Stop.jpg',)

We then get the model’s top five predictions for what this image is, find that our model got it right! The predictions:

class=Stop

class=Speed limit (30km/h)

class=Speed limit (20km/h)

class=Speed limit (70km/h)

class=Bicycles crossing

Conclusion

In this notebook, we explored how to use MXNet to perform a multi-class image classification. While the network we built was simpler than the most sophisticated image-recognition neural network architectures available, even this simpler version was surprisingly performant! We also learned techniques to pre-process image data, we trained the network and stored the trained neural network on the disk. Later, we loaded the pre-trained neural network model to classify images from the web. This model could be deployed as a web service or app (you could build your own what-dog!). You could also use these techniques on other data for the purpose of classification, whether that’s analyzing sentiment and intent in chats with your help desk, or discovering illegal intent in financial behaviors.

In our next notebook, we’ll develop a state-of-the-art sentiment classifier using MXNet.