Backing services for modern application development

Embracing bound resources in cloud-native apps.

Netting (source: jackmac34 via Pixabay)

Netting (source: jackmac34 via Pixabay)

In Beyond the Twelve-Factor App, I present a new set of guidelines that builds on Heroku’s original 12 factors and reflects today’s best practices for building cloud-native applications. I have changed the order of some to indicate a deliberate sense of priority, and added factors such as telemetry, security, and the concept of “API first” that should be considerations for any application that will be running in the cloud. These new 15-factor guidelines are:

- One codebase, one application

- API first

- Dependency management

- Design, build, release, and run

- Configuration, credentials, and code

- Logs

- Disposability

- Backing services

- Environment parity

- Administrative processes

- Port binding

- Stateless processes

- Concurrency

- Telemetry

- Authentication and authorization

The original Factor 4 states that you should treat backing services as bound resources. This sounds like good advice, but in order to follow it we need to know what backing services and bound resources are.

A backing service is any service on which your application relies for its functionality. This is a fairly broad definition, and its wide scope is intentional. Some of the most common types of backing services include data stores, messaging systems, caching systems, and any number of other types of service, including services that perform line-of-business functionality or security.

When building applications designed to run in a cloud environment where the filesystem must be considered ephemeral, you also need to treat file storage or disk as a backing service. You shouldn’t be reading to or writing from files on disk like you might with regular enterprise applications. Instead, file storage should be a backing service that is bound to your application as a resource.

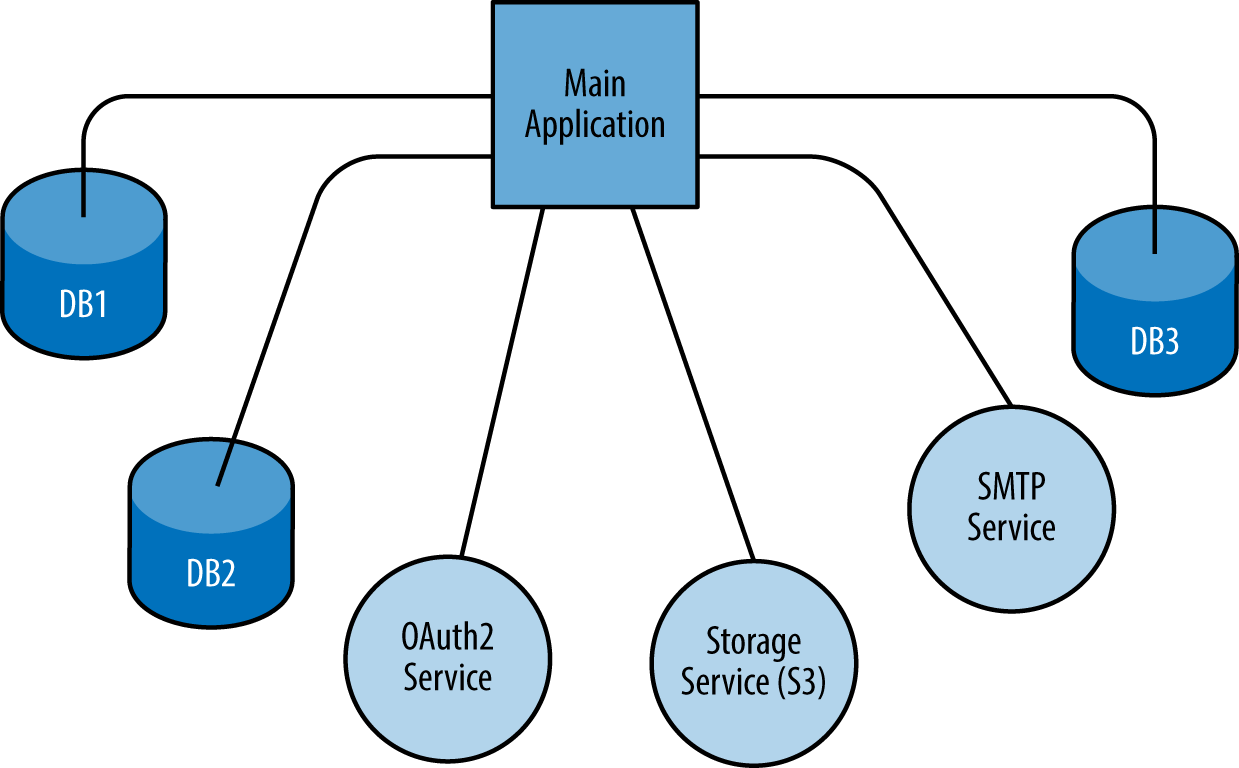

Figure 1 illustrates an application, a set of backing services, and the resource bindings (connecting lines) for those services. Again, note that file storage is an abstraction (e.g., Amazon S3) and not direct OS-level access to a disk.

A bound resource is really just a means of connecting your application to a backing service. A resource binding for a database might include a username, a password, and a URL that allows your application to consume that resource.

We should have externalized configuration (separated from credentials and code) and our release products must be immutable. Applying these other rules to the way in which an application consumes backing services, we end up with a few rules for resource binding:

- An application should declare its need for a given backing service but allow the cloud environment to perform the actual resource binding.

- The binding of an application to its backing services should be done via external configuration.

- It should be possible to attach and detach backing services from an application at will, without re-deploying the application.

As an example, assume that you have an application that needs to communicate with an Oracle database. You code your application such that its reliance on a particular Oracle database is declared (the means of this declaration is usually specific to a language or toolset). The source code to the application assumes that the configuration of the resource binding takes place external to the application.

This means that there is never a line of code in your application that tightly couples the application to a specific backing service. Likewise, you might also have a backing service for sending email, so you know you will communicate with it via SMTP. But the exact implementation of the mail server should have no impact on your application, nor should your application ever rely on that SMTP server existing at a certain location or with specific credentials.

Finally, one of the biggest advantages to treating backing services as bound resources is that when you develop an application with this in mind, it becomes possible to attach and detach bound resources at will.

Note: Circuit breakers

There is a pattern supported by libraries and cloud offerings called the circuit breaker that will allow your code to simply stop communicating with misbehaving backing services, providing a fallback or failsafe path. Since a circuit breaker often resides in the binding area between an application and its backing services, you must first embrace backing services before you can take advantage of circuit breakers.

A cloud-native application that has embraced the bound-resource aspect of backing services has options. An administrator who notices that the database is in its death throes can bring up a fresh instance of that database and then change the binding of your application to point to this new database.

This kind of flexibility, resilience, and loose coupling with backing services is one of the hallmarks of a truly modern, cloud-native application.