2 great benefits of Python generators (and how they changed me forever)

Learn how to elegantly encapsulate and efficiently scale with Python generators.

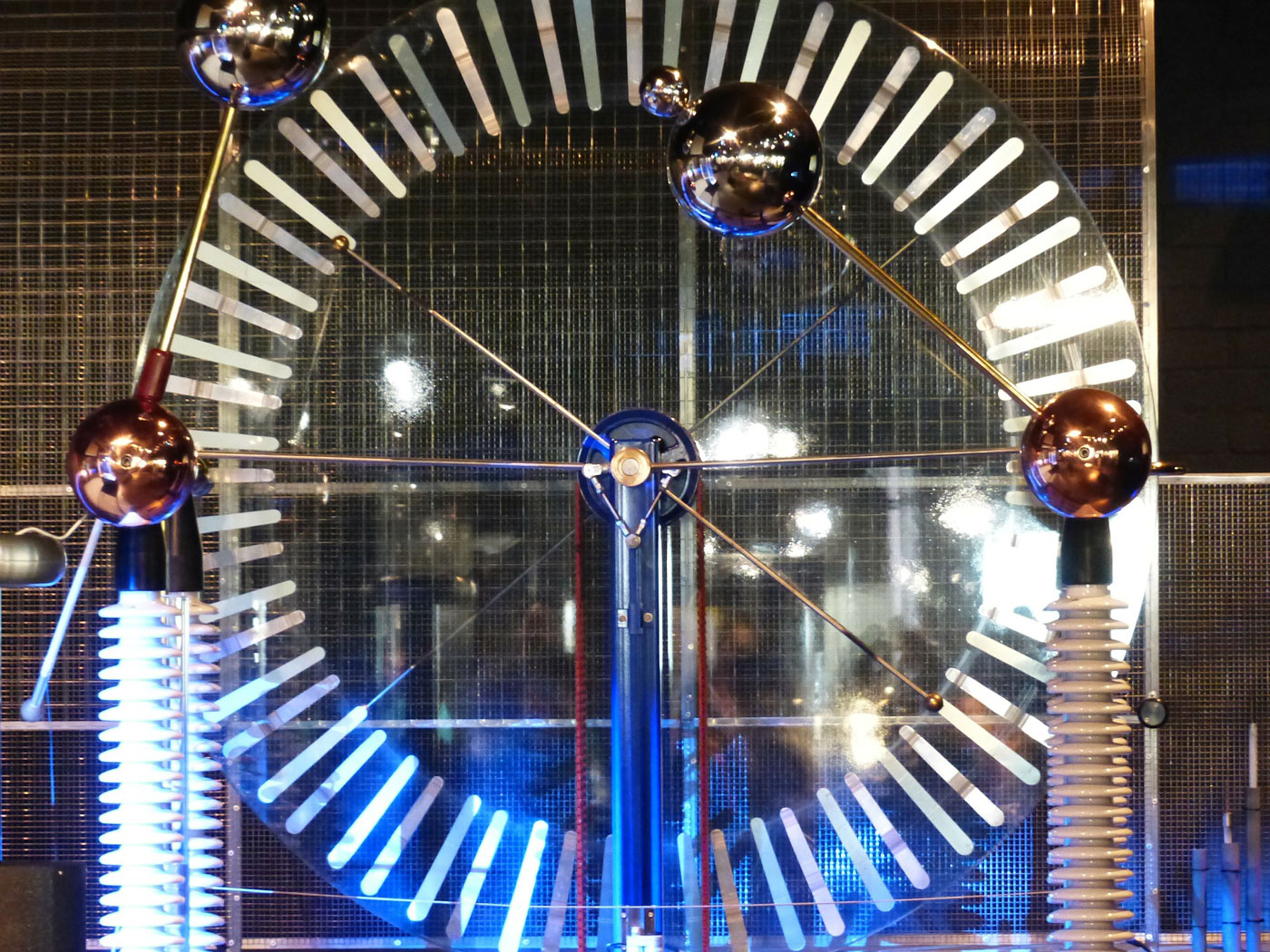

Influenzmaschine (source: Hans via Pixabay)

Influenzmaschine (source: Hans via Pixabay)

I had no idea how important it would turn out to be. It changed the way I wrote software forever, in every language.

By “it,” I mean a Python construct called generators. It’s hard to convey everything they can do for you in a few words; you’ll have to keep reading to find out. In a nutshell: they help your program efficiently scale, while at the same time providing delightful encapsulation patterns. Let me explain.

A generator looks a lot like a function, but uses the keyword “yield” instead of “return” (you can skip ahead a bit if you’re already familiar):

defgen_nums():n=0whilen<4:yieldnn+=1

That’s a generator function. When you call it, it returns a generator object:

>>>nums=gen_nums()>>>type(nums)<class'generator'>

A generator object is a Python iterator, so you can use it in a for loop, like this:

>>>fornuminnums:...(num)0123

(Notice how state is encapsulated within the body of the generator function. That has interesting implications, as you read to the end.) You can also step through one by one, using the built-in next() function:

>>>more_nums=gen_nums()>>>next(more_nums)0>>>next(more_nums)1>>>next(more_nums)2>>>next(more_nums)3

A for-loop effectively calls this each time through the loop, to get the next value. Repeatedly calling next() ourselves makes it easier to see what’s going on. Each time the generator yields, it pauses at that point in the “function.” And when next() is called again, it picks up on the next line. (In this case, that means incrementing the counter, then going back to the top of the while loop.)

What happens if you call next() past the end?

>>>next(more_nums)Traceback(mostrecentcalllast):File"<stdin>",line1,in<module>StopIteration

StopIteration is a built-in exception type, automatically raised once the generator stops yielding. It’s the signal to the for loop to stop, well, looping. Alternatively, you can pass a default value as the second argument to next():

>>>next(more_nums,42)42

Translating

My favorite way to use generators is translating one stream into another. Suppose your application is reading records of data from a large file, in this format:

article:Buzz_Aldrinrequests:2183bytes_served:71437760article:Isaac_Newtonrequests:25810bytes_served:1680833779article:Main_Pagerequests:559944bytes_served:9458944804article:Olympic_Gamesrequests:1173bytes_served:147591514...

This Wikipedia page data shows the total requests for different pages over a single hour. Imagine you want to access this in your program as a sequence of Python dictionaries:

# records is a list of dicts.forrecordinrecords:("{} had {} requests in the past hour".format(record["article"],record["requests"]))

And ideally without slurping in the entire large file. Each record is split over several lines, so you have to do something more sophisticated than “for line in myfile:”. The nicest way I know to solve this problem in Python is using a generator:

defgen_records(path):withopen(path)ashandle:record={}forlineinhandle:ifline=="\n":yieldrecordrecord={}continuekey,value=line.rstrip("\n").split(": ",1)record[key]=value

That lets us do things like:

forrecordingen_records('data.txt'):("{} had {} requests in the past hour".format(record["article"],record["requests"]))

Someone using gen_records doesn’t have to know, or care, that the source is a multiline-record format. There is complexity, yes, because that’s necessary in this situation. But all that complexity is very nicely encapsulated in the generator function!

This pattern is especially valuable with continuous streams, like from a socket connection, or tailing a log file. Imagine a long-running program that listens on some source and continually working with the produced records – generators are perfect for this.

The benefits of generators

On one level, you can think of a Python generator as (among other things) a readable shortcut for creating iterators. Here’s gen_nums again:

defgen_nums():n=0whilen<4:yieldnn+=1

If you couldn’t use “yield,” how would you make an equivalent iterator? Just define a class like this:

classNums:MAX=4def__init__(self):self.current=0def__iter__(self):returnselfdef__next__(self):next_value=self.currentifnext_value>=self.MAX:raiseStopIterationself.current+=1returnnext_value

Yikes. An instance of this works just like the generator object above…

nums=Nums()fornuminnums:(num)>>>nums=Nums()>>>fornuminnums:...(num)0123

…but what a price we paid. Look at how complex that class is, compared to the gen_nums function. Which of these two is easier to read? Which is easier to modify without screwing up your code? Which has the key logic all in one place? For me, the generator is immensely preferable.

And it illustrates the other benefit of generators mentioned earlier: encapsulation. It provides new and useful ways for you to package and isolate internal code dependencies. You can do the same thing with classes, but only by spreading state across several methods, in a way that’s not nearly as easy to understand.

The complexity of the class-based approach may be why I never really learned about iterators until I learned about Python’s yield. That’s embarrassing to admit, because iteration is a critically important concept in software development, independent of language. Compared to using (say) a simple list, iterators tremendously reduce memory footprint; improve scalability; and make your code more responsive to the end user. Through this, Python taught me to be a better programmer in every language.

If you don’t consciously use generators yet, learn to do so. You’ll be so glad you did. That’s why they are a core part of my upcoming Python Beyond the Basics in-person training in Boston on Oct. 10-12, and my Python—The Next Level online training being held Nov. 2-3.